Lead Bloggers: Emily, Matthew and Anna

I. Main Interests

Robles-Durán started the lecture by sharing his background, noting that he works and teaches outside his official appointment. Even though he started his career with architecture, he is interested in it only from the standpoint of a practitioner dealing with consequences of capitalism. His work is influenced by David Harvey and Henri Lefebvre’s Production of Space. Robles-Durán emphasized the need to develop a transdisciplinary perspective for the analysis of space, thus challenging the deterministic and myopic orientation of the academia. He outlined the areas of his interests, some of which were addressed in the lecture and the Q&A section: Anti-speculative (i.e., anti-capitalist) development; Politics of scale; Commons, collectives, shared infrastructures; Development of urban unions; Economies of use value within urban processes; Spaces for political infiltration; Radical representative strategies. The focus of his lecture was on the emergence of supranational agents of neoliberalism and their influence on urbanization.

II. The non-democratic urban world of supranational dominance

When we talk about the beginning of neoliberalism, what is commonly missed is the fact that parallel to privatizations, deregulations and other processes of neoliberalization, there were also changes on a global scale reflected primarily in multinational trade agreements. With the fall of the Iron Curtain, we saw the drafting of the first series of international treaties (NAFTA in 1992, EU in 1993) and the process of internationalization of everything. Governments were working together across the wide array of and regardless of their ideological positionalities. In a short period of time, these agreements created border-crossing commercial lines, with a logic that superseded that of the nation-state. Based on these developments, Robles-Durán posed the following question: Why is it that, regardless of political developments on the local level, the urban trends and patterns have been the same? One can easily observe that since the 1990s, cities around the world has gone through a similar transformation. Robles-Durán proposed to search for the answer in the creation of new supranational institutions accompanying neoliberalization and outlined four conditions that made this global restructuring possible.

Reformed supranational institutions

- Reform of old institutions, such as IMF and World Bank, that function as a consensus apparatus and depositories of neoliberal knowledge, coerce states into accepting treaties and dictate the reconfiguration of space.

- Supranational surveillance, benchmarking & promotion of neoliberalism. Organizations like IMF would need institutions to supervise individual states, benchmark and peer review their progress and change to prescribed standards. OECD is an example of this monitoring type of organisations that also function at supranational level.

- National governments as the agents of supranationals. The first two institutions operate invisibly, removed from the local level; they are regarded as consultant or bank agencies, with no threat to democracy. However, these institutions enter nation-states and coerce them into operating as agents of international organisations, implementing neoliberal agenda. Thus, we cannot direct our resistance against national institutions, since they were forced to become agents of a specific kind of capitalism.

- City governments as opinion shapers. On a local scale, city governments act as agents of transformation. Cities are prompted to become more competitive by OECD and other supranational agents. Cities work together for this purpose, creating networks and alliances. These still operate on supranational level because laws under agreements between cities occupy different space than conflicting laws of sovereign nations.

III. Supranational demands & transformation of territories:

Robles-Durán outlined the demands put forward by these supranational agents that lead to transformation of territories at different scales:

- At global scale, more legal control is given to privately defined supranational organisations, in many cases bypassing constitutional conventions and democratically structured political jurisdiction. They redefine continental and transcontinental trade blocks through the drafting of new corridors, directing the flow of labor, natural resources, manufactured goods, food, services, etc.

- At city scale, treaties encourage urban centers to become more competitive by providing incentives and infrastructure to attract international manufacture, trade, and business hubs. Two types of urban development forced by supranational institutions have become most popular:

- Competition between cities of low-cost sourcing, which entails a reconfiguration of territories for low-cost manufacture;

- Competition between aspiring headquarter cities.

Mass consultancy agencies (independent of IMF and OECD) define these two types of cities (manufacturing and global cities), e.g. UN-Habitat, Deloitte, PWC. They pass down a neoliberal agenda from IMF to city mayors, thus intersecting all scales and shaping new laws that override local laws.

3. Corridors that work outside the logic of any nation state. While nation states continue to financially support urbanization, through classic channels like fiscal redistribution, in order to become competitive players they have to offer more development resources and focus on finding and opening spaces for private investment.

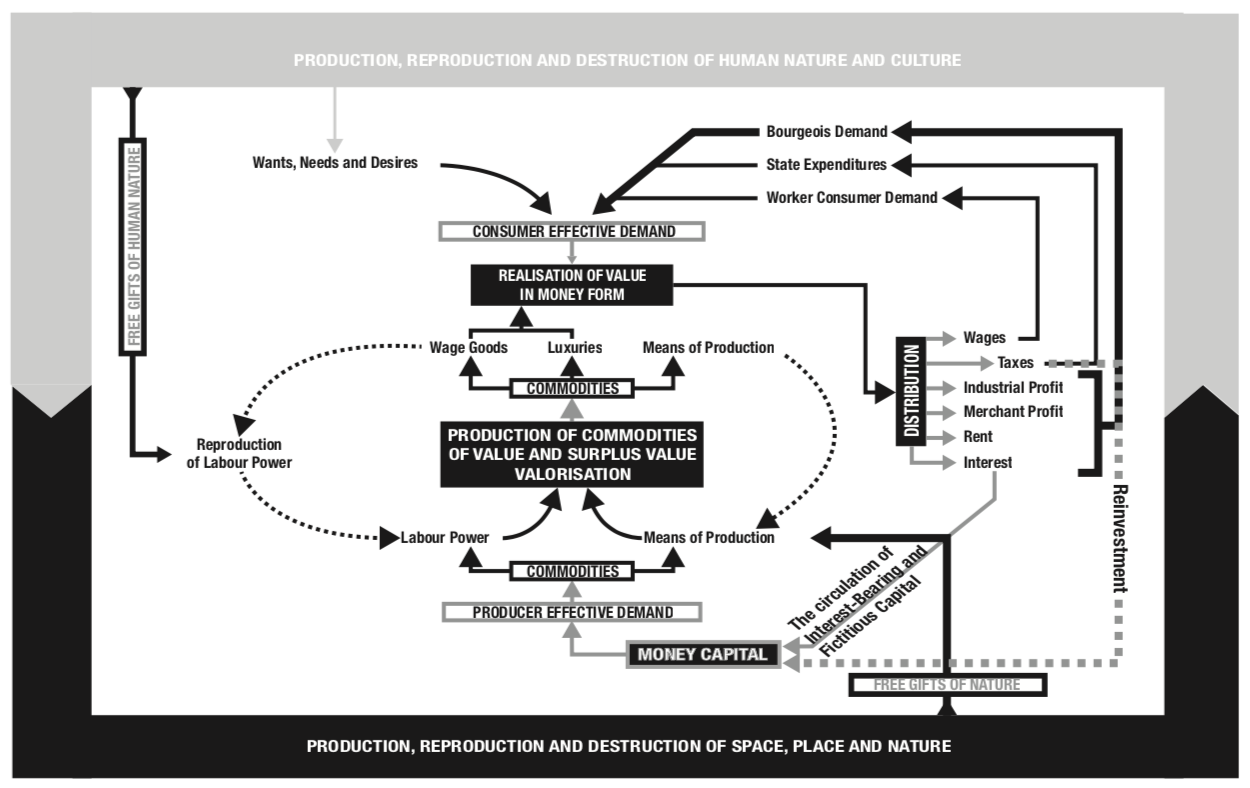

Since the 90s, cities have been trying to fit the same formula of becoming competitive, imposed on them by the same consulting agencies: innovation, promotion of entrepreneurship, creation of business environment, creative class. This homogenization can also be seen in architecture, as it came to physically represent processes of capitalism, and construction of the same cultural attractions, such as museums. Additionally, Robles-Durán notes that this type of benchmarking and metric making has proliferated, even penetrating the logic of cities attempting to resist the neo-liberal agenda (i.e. ranking of municipalist achievements). The result leads Robles-Durán to define urbanization as the “representation of capitalism in space.” Following this definition, he suggests we need a new way to read cities, wherein we consider their temporal and historical aspects, and recognize the ways in which their boundaries as political territories are eroded.

Q&A

During the Q&A portion of the talk, Robles-Durán further articulated both the consequences of embedded neoliberalism in urbanization and potential strategies for intervention and course-correction.

The first question was on the role of prominent urban academics and theorists in legitimizing and perpetuating tropes and systems of global cities, namely Saskia Sassen (here is a link to an article by Sassen that provides an overview and introduction to her concept of “The Global City”). Despite her affiliation with academia and critical research, Robles-Durán situates Sassen and her ilk (particularly Richard Florida) as beholden to the supranational, non-democratic global organizations that perpetuate and disguise extractive strategies for capitalist accumulation. Being an academic, even being a part of the “Left,” does not preclude complicity in these structures and systems. Cities are coerced by these organizations into compliance by heeding strategies of remaining “globally competitive.” Florida’s “Creative Class” has arguably wrought an incredible amount of damage on urban democratic institutions, practices, and landscapes, mainly because its elegance and simplicity were so attractive to cities struggling to revitalize following the financial crises of the 1970s and the deindustrialization of the Global North. Robles-Durán argues that “creative” is really a metaphor of exclusion: upon adopting these strategies to attract both capital and residents, cities made a conscious decision of who and what urban territory was for.

Another question related to strategies of anti-capitalist contestation, namely pedagogical tools, which dovetailed the previous discussion of academics and researchers in urbanism. Robles-Durán urged a broader view, reminding us that “capitalism thinks in centuries.” Shifting the logic of understanding phenomena of change will take time, but it is critical to initiate it now. Younger generations are conscious that something isn’t right, but they lack the tools and language to articulate it–most educational preparation is not grounded in dialectical critiques or comprehensions. Challenging and dissolving arbitrary and anachronistic disciplinary boundaries is another strategy to cultivate new perspectives and critiques, and could empower students to consider problems and processes more comprehensively. His final comment related to scale–engaging with individuals, organizations, institutions at a scale that can match that of supranational institutions.

The role of the traditional nation-state vis-a-vis development (both economic and physical infrastructure) structured the remainder of the talk. The nation-state, historically, provides the capital, vision, and execution of development strategies (and all of the attendant risk). Following the neoliberal turn, however, nation-states began contracting out these roles privately and globally, providing funding but limiting interference with the broader visions and goals of these strategies. This model isn’t limited to infrastructure; it’s reflected at a smaller scale in housing development and employment training to cultivate space for accumulation and labor discipline, outside the aegis of democratic institutions. There is no space for community-driven development because there is no other option: supranational, global institutions curate restructuring at a global scale by subtly coercing nation-states and cities to toe the line– Amazon did this quite effectively, and with little protestation from smaller scales of governance.

Questions

- It is important to consider anticapitalist strategies under the framework of scale–scale is what has leveraged capitalist hegemony globally. What have global examples of resistance looked like historically, if at all? What issue do you see as meaningful and potent juncture for solidarity?

- Following on question 1, after the “alterglobalization” movement, we have largely seen critiques of globalism in mass-media captured by the far-right (i.e. Brexit). What should the framework of a so-called “left exit” of supranational/technocratic institutions (Lexit), premised on left wing demands rather than nativism, look like today?

- While accepting Robles-Durán’s argument about the power that supranational institutions came to have over nation-states in the course of the neoliberalization, is it possible, at the same time, to incorporate into this analysis the role of individual hegemonic states in creating and maintaining these supranational institutions? For example, in The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire (2012), Leo Panitch and Sam Grindin emphasize the role that the US has played in coordinating the management of global capitalism and restructuring of other states, both through its military and financial institutions. How would this argument complicate our thinking about strategies to combat global forces of neoliberalism?