Throughout this series of lectures, we have engaged with seemingly disparate subjects which tie together in their long histories or comes together in the larger network of socio-economical relationships across time and space, an example of this is how the full employment of fixed capital changed the British diet to enjoy bitter marmalade. Bitter marmalade was produced in the 19th century when the Kentish conserve industry needed to keep its fixed capital fully employed through times of the year when there was no more fresh local produce, by getting Spanish oranges in the winter and making bitter marmalade. The challenge we face is how to create a way of thinking these relations effectively which is partly what Marx intended to do in his theory of capital.

It is important to note that Marx had a theory of capital, not of capitalism and when he mentions capitalism its in reference to a “capitalist social formation” or “the capital as a social formation”. He uses the power of abstraction as a means of analysis which exists at a certain level of the general. He states that he’s not interested in the particularities since the particularities will have a different dynamic, an example of this is when he refuses to take on the issue of supply and demand in the first volume of the capital.

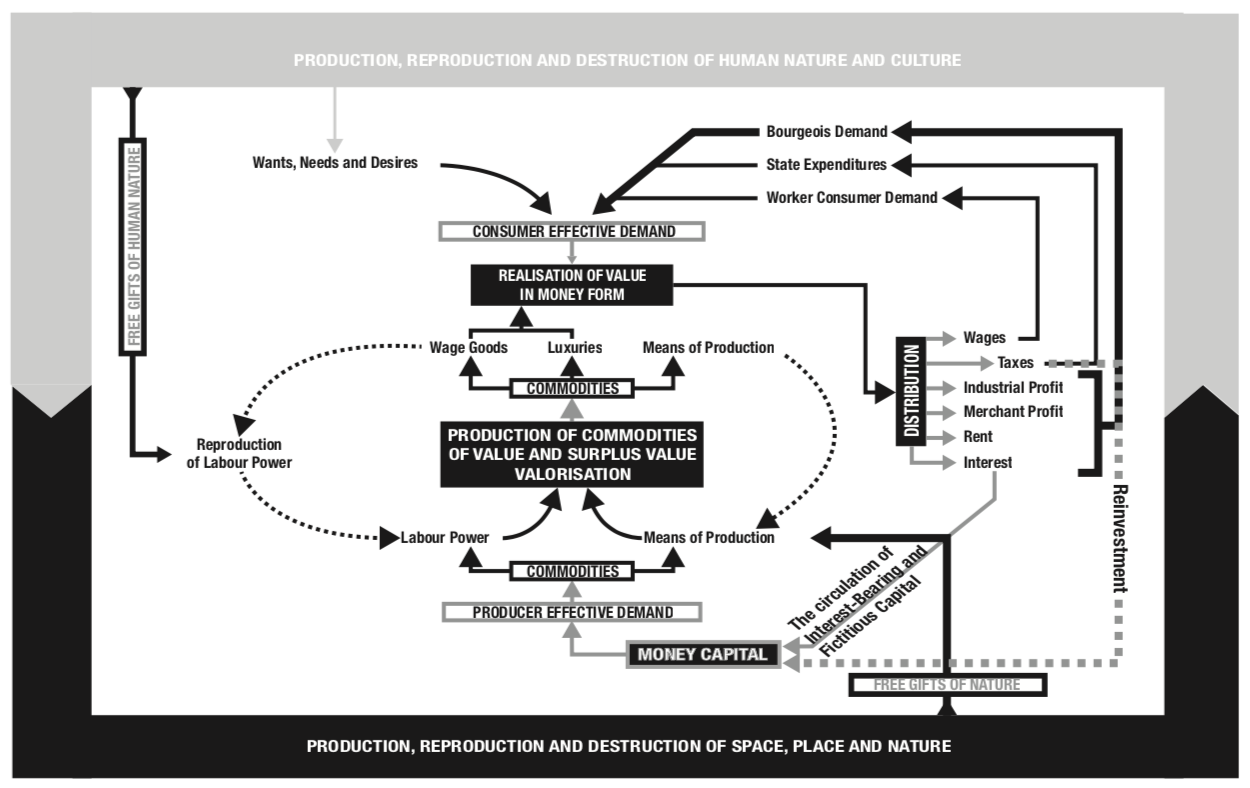

In this lecture series we used a diagram which is an abstraction of capital as value in motion. Money capital becomes the means of production, which becomes a new commodity. The commodity is then taken to the market and sold and the value is monetized. This money is then distributed through wages, taxes (which can both come back as demand) and is then divided between several distributed factions and comes back as reinvestment in the money capital. This system is also an expanding system and its not static. The three volumes of capital integrate in this diagram, volume 1 takes you through the first part of the diagram, left side, in which it’s assumed there are no issues about the problem of distribution or realization of capital. Capital is analyzed from a perspective which asks you to consider all the issues of realization and distribution as constant or irrelevant. In Volume 2 he looks at the realization process, where the market is and how its guaranteed and Volume 3 is about distribution, in each of these volumes the other two perspectives are considered as constant or irrelevant.

So, we have three perspectives on capital which are in these three volumes of capital, placed on this diagram, However its clear from the introductions to these works that these three volumes are meant as part of totality and the totality or “theory of capital” is encompassed by all these volumes.

At the same time there are several contingents and contextual relations that must be there for this process to work out, one of which is the theme of social reproduction, another is the formation of one’s needs and desires (in volume 2) and the free gifts of knowledge, technologies and culture which capital is constantly transforming.These contextual relations are very important and in focusing on each of these themes, as Cindi Katz does with social reproduction, and expanding them new issues can be articulated which haven’t been addressed in the general model.

The same expansion happens when we talk about the production of nature and the metabolic relation to nature.In so doing we realize that this system is inadequate for encompassing the totality of what needs to be addressed however its important to understand that Marx using the power of abstraction is teaching us about the dynamics of this system and some of its laws in motion and those laws of motion have been very significant in what this totality of capitalism is about.

The analogy that I have used in contradictions to capitalism is useful here, if you are on an ocean liner, there may be thousands of things going on, but in the basement, there is an engine room. What Marx does is explain how this engine works, explaining the engine room may not explain everything, or every possible way in which the ocean liner might sink, it might sink for external reasons. However, if the engine stops, we are in real problem, what we see now is that increasingly the globe is being powered with this engine of capital accumulation and the dynamics and internal contradictions of this engine are becoming problematic. The speed and the acceleration and growth of this engine is also accelerating these problems which raises the question how long can the metabolic relations of this system to nature, or culture facilitate this expansion. It seems like this exponential growth cannot continue at the pace in which it has.

However, things are happening that would question these assumptions, it’s not clear that Marx’s value theory is as relevant as it once was. These expansions are no longer necessarily material, instead valuation of knowledge and immaterial elements are now more important than stuff. The way in which for example a corporation is valued is mostly based on expectations rather than material conditions. Therefore, immateriality is the core of what contemporary capitalism is about. If capital can shift from a material base into an immaterial one its in fact becoming something that evades a lot of these contextual constrains. It is possible that we are moving into a new form of capitalism and capital which is not a form that can be best understood using this framework.

Then we must consider if a new model can better explain the reality that we are observing. Central to this model, Harvey argued, is a working understanding of finance. Harvey defined finance as “the circulation of interest-bearing fictitious capital.” Where in Volume I, Marx goes looking for a theory of value and discusses money only as an expression of value within the circulation of capital. The heart of Marx’s model throughout Capital is the manufacture of commodities and the extraction of value, but finance, Harvey argued, is money for money’s own sake, and yet bears tremendous value in the contemporary capitalist system.

Interest-bearing fictitious capital that is lent to families in order to buy land, or money lent to landowners for the purpose of building infrastructure on it, for example, enters the circulation of capital at a very different time and place than goods produced through the factory process. The simple truth of the matter is capitalism is different now. Not only is it more global than ever before but Harvey argued it also is more deeply centered on creating consumer-effective demand and enabling consumption at all costs. While Marx certainly predicted rising debts and an increased importance of interest-bearing fictitious capital, it would have been impossible to predict it would become the basis of an entire debt economy.

With this in mind, Harvey reminds us in his final lecture of how Marx’s own theory of capital changed and evolved significantly from the beginning of Capital Vol. I, through all of the thoughts and essays comprising Vol. 3. Just as Marx’s analysis and critique evolved, so too should our own. Harvey encourages us to develop a new model of the circulation of capital — one updated for the contemporary form of capitalist social structures. In our renewed model for understanding the circulation of capital, Harvey argued we may no longer be able to rely on Marx’s theory as the be-all-end-all of capitalism. Instead, we must find new ways to understand how capitalism exists or else, as Harvey warned us, the theory of capital will remain stagnant. To allow our theories to remain stuck in antiquated modes of production, would be to fail at our most important task in this class: To engage in anti-capitalist action.

The end of the lecture felt almost as if Harvey were responding to all of the course’s most impactful speakers. He listed off areas of capitalism Marx had left unexplored, but which we had discussed this semester. In forming our new model for understanding capital, Harvey encouraged the class to look more closely at racial, gendered, and cultural differenced in the experiences of and functions of capitalism, much like many of the highly-engaging faculty who spoke to us throughout the course. He told us to pay attention to the role of social reproduction in creating not only a capitalist economy, but of a capitalist political and social organization.

Toying at this concept of growing beyond traditional understandings of capital himself, Harvey concluded with an example of how we can apply Marxist theory to new concepts, and update them for the contemporary world. He discussed whether we should view the Chinese government as class traitors for joining the World Trade Organization, and engaging in the coercive laws of competition or if we should try to understand how the needs of the people in China forced the government to join the WTO in order to meet them. Once China had entered the world market, however, Harvey argues they were forced into a situation where, in order to survive, China had to operate under the coercive laws of competition and engage in the exploitation of Chinese labor to make enough from cheap commodities to be able to expand their resources and elevate the standard of living across China.

Q & A

- Knoweldge? On the question of appropriation, how do we speak of it when speaking of knowledge production? How to think on immaterial values through the theory of Accumulation by dispossession, with the history of knowledge so interwoven with epistemicide?

Marx primitive original accumulation ideas are related with the proletarianization process because once the proletariat is form, its formed and has to be dealt with. This is a historical and contemporary process, as observed for example with the proletarianization in China and India of the rural population, where people are being forced out of the land.

However, this is the classical form of appropriation by disposition, surplus value accumulation from the working class. There are also other forms of appropriation, such as the ones that take place not in the Production stage, which is normally related with exploitation, but in the Realization moment. As for example the credit system, speculation in the land value, or knowledge in practice as the pharmaceutical system, when they are able to charge ridiculous prices for patents because of need.

In this sense, Marx and Engels speak of secondary exploitation. We can even speak of economies of dispossession. As when the shopkeeper, the landlord, between other different examples, appropriate by taking advantage of their own role. We can even speak of disposition of rights, as the employees of American Airlines and United who suffered when the companies filed for Bankruptcy. These economies of dispossession became extensive through the neoliberal period due to the need of the expansion of capital.

However, the concept of cognitive capitalism is polemic. Knowledge by itself is not capital. Incorporation of knowledge into the machine and how its incorporated by Capital, its realization, is what Marx was interested in.

- How do you explain the fall of the Soviet Union through the theory of the seven elements?

It has to do with what revolutionary change is all about. The Soviet Union used a single bullet theory. By changing only, the productive forces, they thought they could solve all the other problems. There was no coevolutionary theory of the social and no attention to any of the other seven elements. Which produced a lack of dynamism that ended with its fall.

On the other side, China has not done the same. It says a lot that every regime in China starts off with them doing reforms. There the system is conceived as a totality. In this sense we can understand the importance of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The reading that Marxist tend to make is that capital is about the transformation of the labor process. But what Mao understood is that it’s not just labor, but social relationships. The need to address the cultural understanding and the cultural relations was fundamental for the revolution. In this sense, the Cultural Revolution aimed to take power from the Chinese elite dominating it. Through this we can understand why the detention of Chinese students nowadays is also a result of the strength of the Maoist revolution.

One has to remember that capital was built not because of the labor process during the industrial revolution, but already was set in practice through the accumulation produced by feudal technology. The dependency on the single bullet theory shows why so many revolutionary processes have failed in the last century.

- Social Movements and teaching. A question on the method of presentation. The problem on how to bring the dynamisms of these kind of analysis on to people or social movements that might be looking for concrete solutions on concrete problems.

One of the main conclusions when working with social movements, Harvey states, is that social movements don’t need to be explained their own material conditions or why their being exploited. Most of them have read Marx and even his books. They understand why they are where they are.

However, what can be promoted through teachings and discussions is to conceive their own plight as a continuation of larger scale processes and even see that other similar conflicts arise in different latitudes and have echoes in different geographies.

In conclusion, there is no problem in teaching these subjects to any social movement. They irony of it is that, normally the ones that are recalcitrant on learning it are Graduate Students. There seems to be resistance on learning these subjects between students in different faculties, but it might seem redundant when teaching in a penitentiary, due to that most of the inmates have already have a clear idea of how the system works.

- Totality or Seven? It was asked if how to put together in emancipatory concept both the conception of totality and the seven moments?

To illustrate this point, we started by speaking on the struggle of Taxi unions in China. This example was taken into consideration to discuss a historical moment in which there still was the discussion in China on the possibility of continuing a Maoist kind of governance instead of the entrepreneurial neoliberalism of today. Because of the failure of the first, the second won ground and became the leading model.

In this sense, regionality offer examples that relate to the totality and should not be disregarded. The union of different regional movements, as the resistance in Barcelona of the development of the city and its new urban resistance, can lead to transnational movements.

Lead Bloggers Anthony, Marzieh, and Roberto