Lead Bloggers: Zachary, Stephen and Leo

Professor Gilmore wasn’t able to join us on 11/7, so the seminar participants decided to open up the room for discussion and reflection on the lectures we’ve heard so far from Professors Harvey, Katz, and Robotham. Broadly speaking, we discussed the possibilities and constraints of melding anti-capitalist thought and action. Among other things we touched on the perennial reform v. revolution debate; the prospect of building organizations and broad coalitions for anti-capitalist movements; political education and consciousness; and the role of traditional electoral politics.

Several students voiced concerns over the limits of “reformist” proposals. One student recalled Prof. Robotham’s support of social wealth funds, to which the class had responded with broad skepticism. Wealth fund managers have a fiduciary duty to produce growth/profits. Given this, even public employees’ pension funds (so-called “workers’ capital”) have accelerated gentrification and private infrastructure development in cities around the world. Another student interjected that such reformist proposals might, in fact, “create the conditions for organizing.” Partial public ownership of private companies would open up questions of short- and long-term investment strategies, potentially providing opportunities for political education and mobilization. If nothing else, ordinary people might learn more about corporate structure and financial planning. Education of this sort would, potentially, allow people on the Left to spread their analysis. Millions of people experience the degradations of capitalism, but may not have a specific analysis or platform to articulate opposition to it. Fights for or around social wealth funds – or, as Professor Katz suggested in her lectures, a shorter work week – might give the Left an opportunity to build through action.

In an attempt to rectify the reform/revolution split, one student offered up a working definition of capitalism: a mode of production in which the work to produce the things necessary for people to survive is market dependent and involves the exploitation of the labor force. Acknowledging the difficulty of breaking this market-dependency in the short term, this student urged us to consider the kinds of organizing that might be possible to improve working people’s lives in the short term and simultaneously build class power in the medium- and long-term to oppose counter-revolutionary assaults such as capital strikes or attacks on the currency with mass unrest, general strikes, and so on.

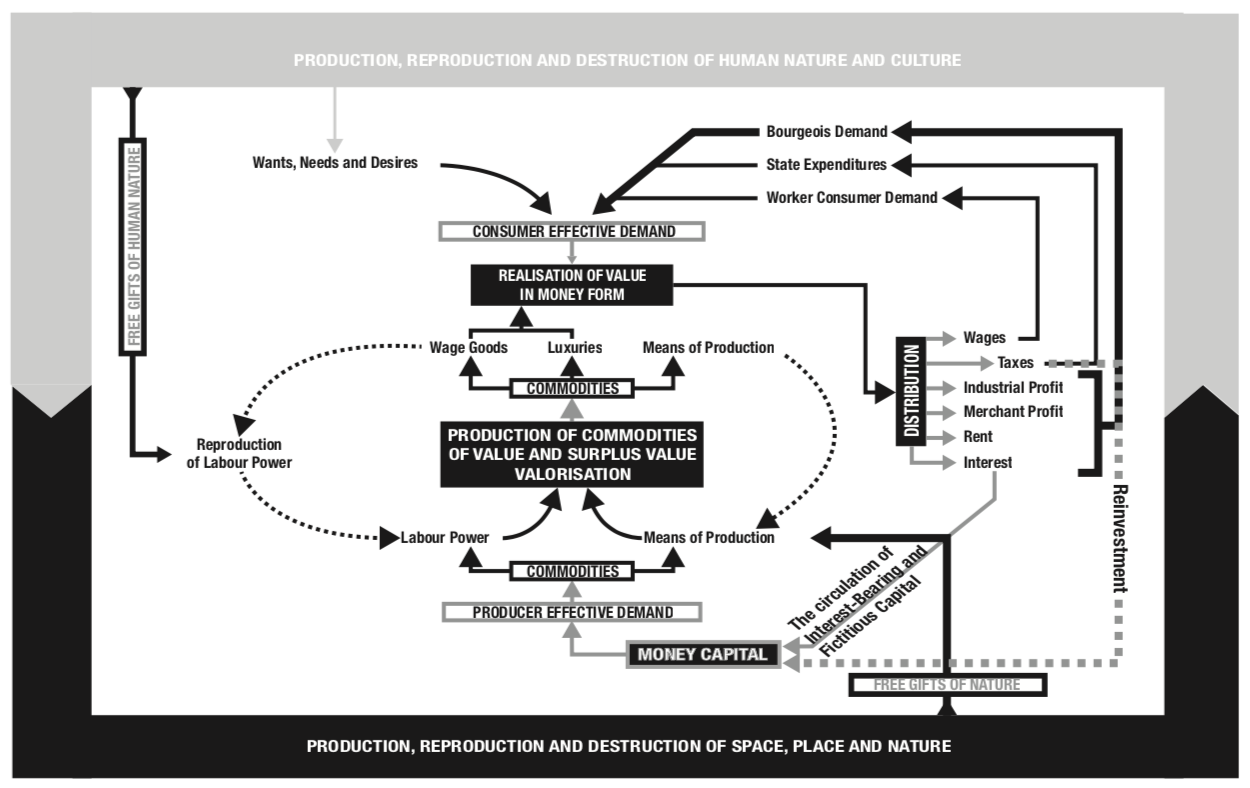

At this point, Prof. Maskovsky intervened to ask how we can continue to have an anticapitalist disposition without falling into calling other initiatives reformist. In his view, there is not only one place from where we can attack capitalism. In fact, he reminded us of Harvey’s argument according to which there are at least seventeen places/moments that are ripe for disruption in contemporary capitalism. These opportunities could even extend if we were to include among them the potential for anti-capitalist action in the realm of social reproduction, as suggested in Prof. Katz’s lectures. Prof. Robotham extended this point to suggest that instead of concentrating in resolving the endless debate between reform and revolution, we should acknowledge that we are in a moment of transition to other forms of political and economic organization, which nature hasn’t yet been figured out. In his opinion, the “central contradiction” of capitalism, is the one existent between the forces of production and the social relations of production. The contemporary Right agrees with the Left that capitalism is broken in this regard. For the Right, however, the solution is more capitalism and greater repression. It is incumbent upon the Left, Robotham stated, to struggle to realize its own solutions to the contemporary crisis.

But how should we fight to win? We discussed the importance of building organizations and broad coalitions in order to realize anti-capitalist action. One student cited Rose Braz and Craig Gilmore’s (2006) “Joining Forces” about a coalition of abolitionist, anti-racist, and environmentalist activists in rural Central California who organized to stop the construction of a new prison. This example shows how ostensibly different groups (young Latinos in rural CA threatened by police, prisons, and pollution; environmentalists fighting for the Kangaroo Rat; the NAACP; and so on) might come to recognize their common interests and power by engaging in concrete political struggles over decidedly non-revolutionary issues, such as the use of public debt. One student raised the successful, on-the-ground organizing of SNCC in rural Southern counties as an example of how the Left might work to create urban-rural coalitions, with a different student concurring and arguing that the Left needs to remedy its current lack of proposals for rural economic development. Another student argued the Left might have a lot to learn from mainstream political parties, who have managed to create extensive coalitions composed of (ostensibly) different people who all identify with a common political platform.

Professor Robotham suggested that the strategy from the left should be to encroach the traditional norms of the rule of law and accumulate the political forces that make reforms possible. In this sense, the left should embrace and defend democracy and align their projects and strategies with those of the Democratic Party. This suggestion echoed a comment made earlier in the lecture by Prof. Maskovsky, for whom democracy today, unlike other moments in the history of the United States, is challenging capitalism in that it opposes its authoritarian turn. In this scenario, the defense of democratic values could be understood as a revolutionary stand. To develop this point, Prof. Robotham posed questions about how the Democrats and the Left might consolidate and expand their respective bases. For his part, Robotham argued the Democrats cannot win with only their base. He recalled his previous comments about the potential for expanding the democratic base to include affluent suburban women who are disaffected by Trump. This idea was met with some resistance from the class, with one student noting that targeting traditionally Republican suburban voters (over both rural and urban voters) was already the strategy of Clinton’s failed 2016 campaign. Jeff registered some concern about what the Democrats might have to compromise in order to gain support from rural whites. The question of whether the Left should struggle within the Democratic party or form their own party was raised but left unanswered.

Considering our wide-ranging discussion, we propose the following questions:

- How should we think about building for the transition from capitalism? How do we distinguish between reforms that build towards a transition and reforms that merely prop up or strengthen capital’s hegemony?

- Professor Robotham suggested that by concentrating in giving answers to the contradiction existent between the means and the relations of production, the left would be able to build broader political alliances and gain the vote of rural working-class population. Is this political strategy sufficient to attract this type of vote? What about the conservative values in terms of race and gender that strongly shape the political sensibilities of the Republican voters, or more generally, of conservative middle classes in Latin America (as in the case of Brazil)? Should the left temper or abandon its claims on racial and gender equality and concentrate on economic differences on the name of electoral success?

- What, in your understanding, is the contradiction between the forces of production and the social relations of production? What opportunities for anti-capitalist movement are presented by this contradiction?

- What should be the anti-capitalist stand on democracy?

- What kind of organizing, around what kind of issues, should we envision to knit together otherwise different communities and spaces into powerful coalitions (urban/rural, for example)? To what extent should we rely on already-existing organizations (labor unions, political parties, non-profits, and so on)?

- How should the Left spread its anti-capitalist analysis to oppose right-wing elites like Bannon and grassroots populist movements? What is the role of art and other cultural practices in political education?

References:

Braz, Rose. “Joining Forces: Prisons and Environmental Justice in Recent California Organizing.” Radical History Review 96, 2006: 95-111.

Harvey, David. Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism. London: Profile Books, 2014.

Thanks for the great summary of our broad-ranging discussion.

Question 5 makes me think in particular about how we conceive of urban-rural coalitions and other unlikely alliances. There are ways of organizing that make shared, rather than sectional, interests of urban and rural populations into a concrete, shared ground for organizing (and, it bears repeating, that rural spaces are far from uniformly white in the United States). In my experience of organizing, it’s astonishing how much more quickly consciousness changes through shared struggle (as in a union contract fight, a fight against upzoning, a fight against prison or jail construction or toxic waste dumping etc.) than through liberals’ miniature “re-education” campaigns like sensitivity/diversity trainings or anti-oppression workshops. Some of those techniques can be helpful if integrated into concrete fights, but when politics becomes about hectoring people’s incomplete consciousness rather than seeking shared interests between disparate spaces, I think we are even more set up to lose.

A lot of people make assumptions about which coalitions are possible, as encapsulated even in radical versions of “Red State / Blue State” description-as-analysis, and don’t look for some subterranean links between, for instance, urban and rural places abandoned by capital (see Gilmore ____). Unlikely alliances over partial struggles over “non-reformist reforms” (or even reformist ones) can, if strong organizers are present and take the opportunity, fashion newly emerging, potentially anticapitalist forms of consciousness into a broader movement. Walter Rodney’s lectures on The Russian Revolution (A View from the Third World) took this seriously, analyzing the Bolsheviks’ strategic linking of proletariat and peasantry to find potential implications for urban-rural communist organizing in ethnically diverse countries (which is, really, most of them in the world) like Guyana or Tanzania. We should too—think of politics dialectically. Consciousness changes through interaction with (and the transformation of) the social world. Don’t write people off as lost causes.

====

Angus, Charlie. 2013. Unlikely Radicals: The Story of the Adams Mine Dump War. Toronto: Between the Lines Press.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2008. “Forgotten Spaces and the Seeds of Grassroots Planning.” In Engaging Contradictions: Theory, Politics, and Methods of Activist Scholarship. Ed. Charles R. Hale. Berkeley: UC Press.

Rodney, Walter. 2018. The Russian Revolution: A View from the Third World. London and New York: Verso.

Thanks for the great summary of a winding conversation!!

What kind of organizing, around what kind of issues, should we envision to knit together otherwise different communities and spaces into powerful coalitions (urban/rural, for example)? To what extent should we rely on already-existing organizations (labor unions, political parties, non-profits, and so on)?

We should be careful not to assume that we can know what alliances or issues will make sense before these alliances and issues emerge. In other words, the politics cannot be formed by thinking about them, but will necesarily unfold in the doing. While we can be strategic, we should be ready for suprising coalitions, and out-of–the-blue issues to become politically salient. In this same sense, the local and historical context here cannot be stressed enough. The coalition that fights (is fighting) prison construction in Brooklyn will not be the same one, and perhaps in shocking ways, that organizes to fight one in Rio de Janeiro. Nor in Connecticut for that matter. It is not always necessary for these groups to be fighting the same issues for them to be fighting the same fight.

Thanks for a great summary.

I believe that the debate between reform and revolution is still as relevant today as when Rosa Luxemburg published her famous essay “Reform or Revolution” almost 120 years ago. In it, she made clear that we should not discard reforms altogether. As she put it “between social reforms and revolution there exists for the social democracy an indissoluble tie. The struggle for reforms is its means; the social revolution, its aim.” In other words, social reforms should never be seen as ends in themselves but as means to reach the final goal; the revolution. Personally, I have always grappled with this question.

On the one hand, it is clear that, overall, social reforms do not constitute “threat[s] to capitalist exploitation, but simply the regulation of exploitation.” On the other hand, it seems ludicrous to oppose social reforms out of principle while waiting for “le grand soir”, the global revolution that will overthrow capitalism altogether. However, one look at the history of Latin America shows how precarious and easily overturned social reforms can be. From the experience of Jacobo Arben Guzman in Guatemala in the 1950s, to that of Salvador Allende in Chile in the 1970s or, more recently, of the PT in Brazil, history has shown us that even relatively modest reforms are met with the most brutal backlash from the capitalist class and its allies. I’d really be interested to hear what people make of these contradictory observations and if you have any insight of how to overcome them.

– Helen Scott (ed.). 2008. The Essential Rosa Luxemburg – Reform or Revolution & The Mass Strike. Chicago: Haymarket Books

The foundation for community and mutual feelings of connection that transpire mainly through shared struggle and/or labor is an extremely important concept that coalitions and organizations need to fully adopt in order to achieve the amount of support required to make changes in opposition to the capitalist agenda. Fighting the same overarching fight (ex: against more capitalism) in comparison to fighting for the same issue (ex: shorter work week) would not foster the kind of support needed to overthrow a large political/corporate/financial figure and would do little to change outcomes that benefit those in positions of power. Large scale momentum concerning one goal has been proven to be effective although the change may have taken place over a longer period of time than desired. For example, paid family leave has received an enormous amount of attention in recent years and many corporations, nonprofits and even state governments have adopted left-leaning policies by either introducing paid family leave or providing longer leave for employees/constituents. This has been a nation-wide issue for over a century that affects every single working-class family in this country, yet only in the recent decade are we seeing these policies which are reflective of strong and consistent national support. As much as definitively writing people off as lost causes furthers the current political divide and leaves us in an assumingly worse position, attacking a powerful system with 30 different battles in an effort to reign in capitalism on a large scale will accomplish little else.

I’m not speaking in favor of only combating one small issue at a time as nation so by the time my grandchildren have children we start to see real progress, but strategically gathering a vast net of support for more tapered issues (ex: corporate tax reform or eliminating (not decreasing) usage of fossil fuels) by combining varied efforts of struggle will yield greater results.

I would like to address someone’s suggestion in the beginning of the class to reconsider the ways in which we assess achievements of a social movement or struggle when there are no material gains, i.e. direct impact on structures of political and economic power.

In this regard, Ida Susser’s work on the recent commons movements provides a useful framework for analyzing long-term consequences of protest movements that do not directly lead to concrete reforms (leave alone overthrow of a government). In her 2017 article “Commoning in NYC, Barcelona, and Paris,” she looks at the square occupation movements in three cities (Occupy, 15-M, and Nuit Debout) in terms of their indirect structural impact that is often overlooked by critics and sympathetic commentators. She argues that they provided a space for the reconfiguration of political discourse and formation of a new political bloc that united various grassroots groups and struggles under the same cause. These developments, in turn, precipitated structural political changes on a municipal or national level, such as a new progressive legislation or electoral campaign (namely, those of de Blasio and Sanders in the USA, Barcelona en Comu in Spain, and Melenchon in France).

Thus, we can give full credit to protest movements for raising consciousness of their participants and onlookers, bringing new people into struggle, and opening up space for further engagement.

Susser recognizes, of course, the limits to the progressiveness of de Blasio or Sanders. My question is then, how do movements that give rise to such electoral campaigns, can also push or continue pushing them further to the left? This seems to be especially relevant now, as we have people like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in Congress –how can the grassroots movement that has enabled her victory ensure that, despite structural constraints of the Democratic Party, she will fight for her campaign promises and more? So that electoral politics and the Democratic Party are used as tactical tools to advance a much more radical vision that they can allow at the current moment.

Susser, Ida. “Commoning in New York City, Barcelona, and Paris: Notes and observations from the field.” Focaal—Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology 79 (2017): 6-22.

Another note on Prof. Maskovsky’s suggestion to reframe the discussion of reform vs revolution as that of Gramsci’s war of position vs war of maneuver. I’ve encountered the same framing while reading Kali Akuno’s article “Casting Shadows: Chokwe Lumumba and the Struggle for Racial Justice and Economic Democracy in Jackson, Mississippi” and it made a lot of sense to see how they apply this framework to concrete actions and circumstances, in particular, to balance their efforts to organize outside the electoral arena with electoral engagement (“engagement with the state”) (2017, 236).

I think that looking at the concrete experiences of Cooperation Jackson answers in a way the first question put forth by the lead bloggers. Kali Akuno emphasizes the need to distinguish “between, on the one hand, acts of positioning, such as building allies, assembling resources, and changing the dominant social narratives, and on the other hand, acts of maneuvering, such as open confrontation and conflict with the repressive forces of the state and capital” (236). Cooperation Jackson has been pursuing two-pronged strategy following this framework: on the one hand, they have been trying to build “autonomous” or “self-reliant” social projects, like community gardens, housing occupations, worker coops, educational/training centers, etc.—projects that would provide resources for people (such as time) to engage in further initiatives, including the ones that they define as “positional,” e.g. pushing for reforms like police control boards (234-235). The second part of their project involves putting pressure on the government and the economic forces through mass protests, direct action, boycotts, etc., i.e. “offensive” actions that aim at changing existing or proposed legislation and directly confront the state and capital. Cooperation Jackson has engaged in electoral campaigns, successfully electing Chokwe Lumumba and, after his sudden death, his son Chokwe Antar. They view this as a temporary tactical engagement to influence affairs on a municipal level—appropriate under the circumstances of these particular elections—and fully realize the limitations of this tactic (238). It is insightful to read their assessment of the mayor Chokwe Lumumba’s actions during his time in the office (242-243).

Akuno, Kali. “Casting Shadows: Chokwe Lumumba and the Struggle for Racial Justice and Economic Democracy in Jackson, Mississippi.” In Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-Determination in Jackson, Mississippi, edited by Kali Akuno & Ajamu Nangwaya. Montreal: Daraja Press, 2017.

I want to first thank the above commentator for incorporating our class discussion over Gramscian ideas about war of position vs war of maneuver. Our in-class discussion was in many ways framed and reframed through these ideas, from start to finish. And to some extent, I found it quite generative to constrain the many strains which were brought up about coalitional building, the history of the rise of right politics in the US, and as the finer details between reformism and revolt. Of course, if we are to engage with Gramscian grammar, then we must contend with his ideas as to how the subterranean politics happening beneath the political discourses approved by the state and civil society. Thus, the site of political is as important to the effective movement of a social formation, as is its political will and ideas. We, often, understand this grammar in terms of consent/coercion, yet Gramsci was also as interested in censorship which he brought out in a discussion on Machiavelli’s realpolik and the French Revolution.

Gramsci states,

“The reason for the failures of the successive attempts to create a national-popular collective will is to be sought in the existence of certain specific social groups which were formed at the dissolution of the Communal bourgeoisie; in the particular character of other groups which reflect the international function of Italy as seat of the Church and depositary of the Holy Roman Empire; and so on. This function and the position which results from it brought about an internal situation which may be called ‘economiccorporate’ politically, the worst of all forms of feudal society, the least progressive and the most stagnant. An effective Jacobin force was always missing, and could not be constituted; and it was precisely such a Jacobin force which in other nations awakened and organized the national-popular collective will, and founded the modern states…

Traditionally the forces of opposition have been the landed aristocracy and, more generally, landed property as a whole with its characteristic Italian feature which is a special ‘rural bourgeoisie’, a legacy of parasitism bequeathed to modern times by the disintegration as a class of the Communal bourgeoisie (the hundred cities, the cities of silence). The positive conditions are to be sought in the existence of urban social groups which have attained an adequate development in the field of industrial production and a certain level of historicopolitical culture. Any formation of a national-popular collective will is impossible unless the great mass of peasant farmers bursts simultaneously into political life. That was Machiavelli’s intention through the reform of the militia, and it was achieved by the Jacobins in the French Revolution. That Machiavelli understood it reveals a precocious Jacobinism that is the (more or less fertile) germ of his conception of national revolution. All history from 1815 onwards shows the efforts of the traditional classes to prevent the formation of a collective will of this kind, and to maintain

‘economic-corporate’ power in an international system of passive equilibrium” (pgs. 241-242).

The problem, in reading, Gramsci’s prison notebooks is that his ideas (or at least the things discussed) are context specific, specifically his struggles against the Italian fascist state. Notwithstanding, as always, Gramsci provide glimpses into what political struggle looks like from below, or from the south, pick your metaphor. And key to these ideas was how he understood the “failure” of the French Revolution which was the inability, in Italy during the time, of its intellectual culture defined by its aloofness of the dominant social group which emerged as the mode of production changed (from agrarian into the early modern period). Intellectualism was, in Italy, largely dominated by an elite class that was closely interrelated with ecclesiastical society. This does not mean Italy’s intellectuals were simple-minded, in fact it was the opposite they were high-minded cosmopolitans who spoke of themselves in universal terms. This is the contradiction, then, the Machiavellianism which undergirded Jacobin thought, which in turn was integral to bourgoisie upheavals in other nations that were in the midst of upturning monarchies and establishing states, was, in Italy, at the time, not able to take hold. The new guard of intellectuals simply could not absorb the traditional intellectuals. Instead they were neutralized. What I would call censured.

But what then is censure exactly. Let’s return to Gramsci’s explanation of how fascism must be countered: “Only with the greatest concentration and intensity of party activity can one succeed in neutralizing atleast in part this negative factor, and in preventing it from hampering greatly the revolutionary process” (p. 159). The negative factor being “the repression exercised by Fascism with the aim of preventing the real relation of forces from being translated into a relation of organized forces” (p. 159). This represssion, or neutralizing, or censor, was, for Gramsci, not unique to the left or right of the political spectrum, but in principle something radical politics must always contend with.

But then if we take Gramsci seriously, and incorporate, what he thought about political neutralization to our current conjuncture. I wonder if we might be able to understand censure through “distraction politics.” Key to Trump’s politics, in my estimation, is his ability to convert the political machine into a war of attrition. He simply lies and deflects, so that pinning him does not actually unsettle his political base (rhetorically or constituently), and as well Trump causes so many culture wars to bubble out into the streets that people become tired. Moreover, this means subterranean politics that pride themselves on being in front must choose to censure themselves. Decisions to engage or disengage is forced to the forefront of political action now, in a radical sense, or the avantgarde risk running around in circles. In this way, Trump despite all his buffoonary has not hampered Republican politics to the point that it can’t force through a implicit repeal of the Affordable Care Act, or a Texas judge from forcing the Supreme Court’s decision on ACA.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/u-s-house-passes-republican-health-bill-a-step-toward-obamacare-repeal/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/federal-judge-in-texas-rules-obama-health-care-law-unconstitutional/2018/12/14/9e8bb5a2-fd63-11e8-862a-b6a6f3ce8199_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.ece818e2cdf7

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/14/health/obamacare-unconstitutional-texas-judge.html

While I am truly in agreement with Don’s call that leftist politics, at this moment, must be capable of articulating more than what its against since even the right is against neoliberalism; that lefist politics must instead be able to articulate what its for. However, if we filter everything through wars of position/maneuver are we skipping a step in the analysis? what is the point of winning, if there are no tangible policy ideas that are relevant to working people today, or tap into radical ways of rethinking the relationship between the political and economic? It is certainly trendy within subterranean politics to be attuned to Gramscian ideas, I am just not as certain if this is coming at the expense of censoring the “thinking differently” that our current conjunture calls for. The neoliberal agenda has made itself clear, after 2008, they are doubling down. This is causing all sorts of social unrest. Should the left be ok with simply doubling down on staid policies, trojan horses, or high-minded ideas about “winning”? I mean what do we win? And are we so certain as to how new thinking is being neutralized?

Gramsci, Antonio. 2000. The Gramsci reader: selected writings, 1916-1935, trans. David Forgacs. (New York: NYU Press).