[lead bloggers: Laura Rivas Burgos, Roberto Elvira, and Nicolas Benacerraf]

In this week’s lecture, David Harvey reflected on Marx’s value theory, which is often mistaken for the “labor theory of value” discussed by classical economists. While Marx did engage the “labor theory of value” to formulate his own ideas around value production, he did so in a critical spirit and from a point of contention.

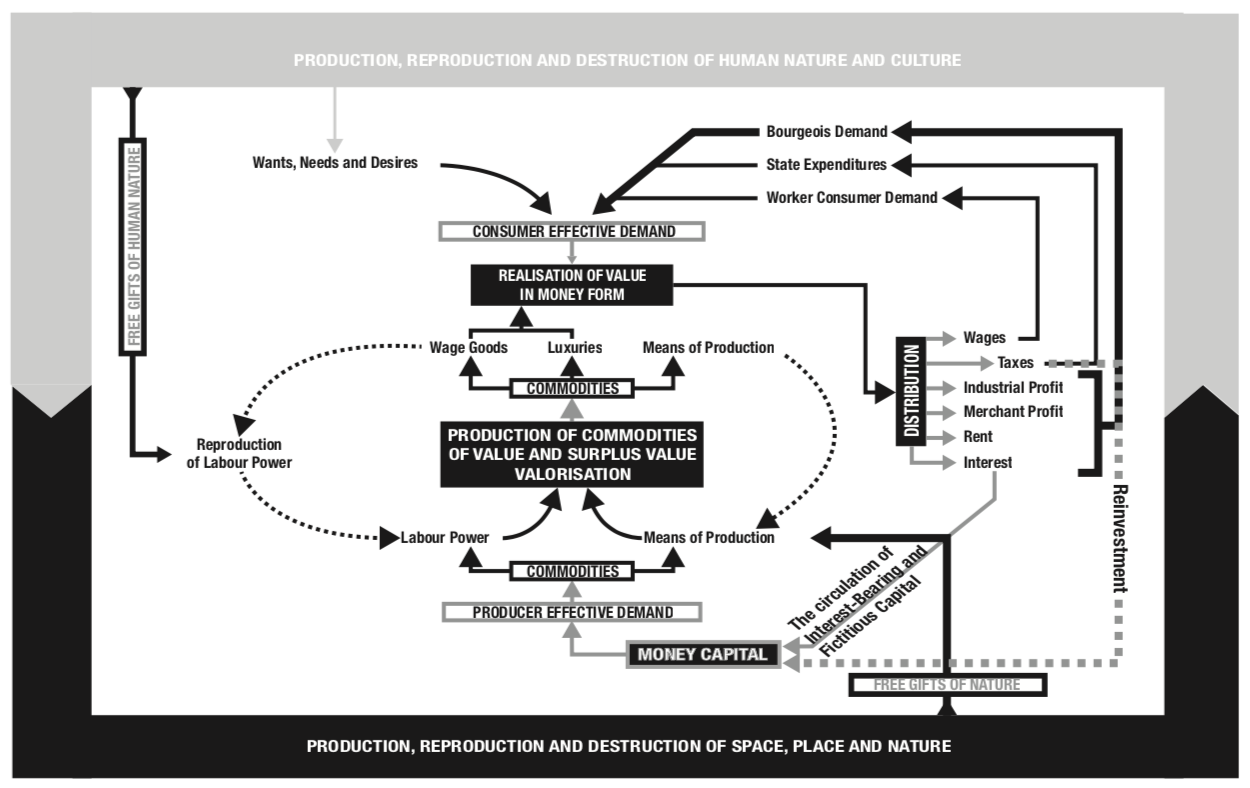

In order to explain how Marx’s concept of value works, Harvey revisited the six introductory chapters of Capital, Volume I, where Marx observed that the process of commodity exchange is facilitated by a common social standard of measurement (money). More precisely, different use values suddenly become commensurate in exchange under the larger umbrella of value. David Ricardo had previously equated value to congealed labor time, but Marx would distinctly qualify this statement to affirm that value is *socially necessary* labor time. As such, value is not simply a quantitative expression, or intrinsic, but is actually contingent on a series of social processes tied to the spheres of production and circulation where value is realized.

Value can only exist in a society where commodity exchange has become normalized, which in turn requires the existence of money to facilitate such exchange. Money is value’s form of appearance; a material representation of value that quantitatively expresses it, as well as a vehicle for its realization. But price and value are not the same. Whereas Ricardo was concerned with the former, Marx understood the potential incongruities between these two concepts and (in Volume I) was more interested in the consequences of value production for the worker. As such, his analysis transitioned into the production phase to better grasp how value is constituted through material activity.

The “coercive force of competition” compels capitalists to implement certain practices in the production phase (e.g. the extension of the working day) in order to maximize surplus value. Similarly, in order to boost relative surplus value, capitalists introduce cooperation, the division of labor, technological innovations, and so forth. Some of these measures eventually affect the organic composition of capital. For instance, technological innovations may result in an increase of constant capital at the expense of variable capital, reducing the proportion of labor power involved in the production process. The release of workers contributes to the formation of an industrial reserve army—a mass of potential workers living in immiserated conditions of social reproduction. This surplus of labor power fulfills the important role of keeping wages low, thus yielding more surplus value for the capitalist. As such, value as it is conceived in the market is constantly being revolutionized through modifications at the level of production and at the expense of the worker. Marx’s distinctive value theory expresses the contradictory unity of the labor theory of value (exposed in the first 6 chapters of Capital Volume I) and the “value theory of labor” (as Diane Elson calls it) in the sphere of production. In many ways then, Harvey suggests, the theory of value is also a theory about the conditions of the worker; a theory of the alienation of workers from the fruits of production.

This interpretation of the value theory illuminates certain contradictions within the process of value production. This takes us to the second section of Harvey’s lecture, concerning the falling rate of profit. In Capital, Volume III, Marx explores how labor-saving technologies have a tendency to reduce the overall surplus value. That is, a decrease in labor input also results in a falling rate of profit because workers are the ones who actually produce value. However, commodities need to be sold in order for this value to be realized. This dynamic introduces a contradictory relation between competitive market processes that seek to yield more surplus value and the miserable conditions of social reproduction that these processes produce. That said, although the rate of profit is prone to decrease over time, the overall mass might still increase. And the proportion of profit that is allocated to the capitalist class also increases, producing a growing income disparity. There is a fundamental disconnect between the conditions in which value is produced and the conditions in which it is realized. Poor conditions of social reproduction drive consumption power down, leading to a crisis in realization. Again, this is an instance where we can observe that the capitalist experiences alienation. Here, alienated social power manifests itself and confronts society as an autonomous social *thing* that exists above and beyond the individual participants of all classes.

The regularity of market crises – momentary violent solutions that restore balance to the “limit cases” of capitalism – expose the inherent limits and contradictions of capitalist organization. To overcome those limits, the markets expand. Marx anticipated the building of a world market, which he called the destiny of the Bourgeoisie (Communist Manifesto). Only through the realization of surplus capital can crisis (“realization barriers”) be overcome, and this realization takes place in the act of consumption (be it final consumption or productive consumption). Accordingly, the increasing insufficiency of local or national realization obliges the expansion of capital on a global scale. The crisis of 2007/2008, which sprung in the subprime mortgage of the real-estate in the southern USA, was resolved through the productive consumption of China, which through infrastructural investment broke the barrier of realization by absorbing the surplus of capital and labor circulating at that time.

Discussion Questions

1) Harvey mentioned that crises in capital do not represent endpoints, but violent solutions that restore order to existing contradictions. In what sort of situations could these crises and contradictions represent – if not an endpoint to capital – at least a threshold for articulating anticapitalist thought and action?

2) In Capitalism, price functions as a representation of value, offering a material substitution for an abstract/immaterial concept. Part of the job of anticapitalists is to articulate the alternative forms of value that are excluded from the capitalist model. What are some examples of movements, actions, or authors that reveal other alternative forms of value? Might this relate to the prospect of inventing “socialist money”, which Harvey alluded to during the lecture?

3) Alienation is both a condition of the exploited as of the exploiter – of the laborer and of the capitalist. However, how do these forms of alienation differ? Is it enough to state that one is of the production and the other one of the realization process? If alienation is an integral part of the capitalist system, and if time (when) and space (where) class identity (who) are also a part of it, what role does context play in the experience of alienation?

4) We will post summaries of the questions that were asked in person during the lecture. You might choose to continue one of those threads.