Colin, Marty, and Hugo

We are living in a dangerous moment. The forces on the right are on the march. They have a unified message and a clear leader, a political and economic program, and the power of the state. The left and progressive movement is outraged and defiant but not acting with the same cohesion. We are in for a very long haul and need to think strategically, not only in this country, but in Brazil, Eastern Europe, Turkey, the forces are simmering in Germany. But while these dynamics are not confined to one country, it is important to think about the specifics and particularities in every instance.

Marxism as a form of historical materialism:

Like other bodies of thought, Marxism has both a broad general value and simultaneously the specificity of arising in a specific time and place. Marx and Engels studied the development of capitalism in Western Europe, particularly in Britain. But the achievement of Marx transcends time and place. Marx was able to extract the fundamental core of the capitalist system which reproduces itself wherever capitalism goes. At the heart of the matter, the capitalist system is based on private ownership of the means of production and the exploitation of wage labor. This is a universal feature of capitalism, and a whole system of contradictions develops out of this.

Despite these universally applicable core relations, the way capitalism developed in Britain is not the same way it developed in China, Egypt, Brazil, Argentina, etc. In each case, specific features vary across contexts. Japan, Russia, China all tried, for example, to allow capitalism to develop without the old elites losing their position. In the U.S. context, the Civil War had widespread destruction of the old plantocracy in the South. As capitalism began to emerge in the post-Civil War period it was relatively less racist, and then it’s reversed. And this then brings racism into the center of the political and economic history and life of the U.S. It’s a very distinctively U.S. development, very specific to how the U.S. develops. But it’s capitalism, and the broad features of capitalism in the U.S. are no different from the broad features of capitalism anywhere else.

But it’s absolutely crucial, especially politically, to understand what is historically specific to each capitalism, to study, in each instance, which political alliances are generated. It is critical to get away from Eurocentrism in our thinking; Eurocentrism affects Marxism too. This requires us to recover the historical agency of actors in different historical contexts. We can’t apply Manchester to China, or what unfolded in the U.S. to Egypt. To practice a science of the concrete means to be able to take the core features of capitalism and see how they are deeply inserted in the historical specifics. If we aren’t able to do this, we won’t be able to move the political needle. It is not possible to connect with people simply with an abstract theory. It is impossible to apply Marxism in a mechanical way, without deeply grounding it in historical specifics.

But that is not to say we should create a new Marxism. There are general truths of universal importance. Marx’s 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte is the classic example; it can’t be read often enough. In it we see the distance between an abstract grasp of theory and the concrete application with surprising and creative results. Lenin and Mao both grasped this. Manchester or Dutch development can’t be mechanically applied to Russia or China. We need to deeply embed our analysis in a historical way.

Marxism as a dialectical materialism:

This is an old Hegelian story, that of the contradictions, but it is a crucial part of Marxism. It is not a positivism. We can think of dialectics as a “pro” and “con” which inevitably arise out of a particular political situation, in which the two sides are actually irreconcilable within the existing frame of things. If the “pro” is the future, or the historical future struggling to emerge, and the “con” is the past, or the past embedded in the present, we can see the dialectical present as the irreconcilable fight to the end in which one side is going to prevail. This is a deep historical process in which the irreconcilability of the positions drive a process of political and social transformation, out of which a new political and social regime emerges.

This type of dialectical analysis which is directly derived from Hegel is formulated in idealist terms. That is to say, this is a struggle in consciousness, in ways of thinking. So there’s a dialectic between old and new ways of thinking, and the issue is which way of thinking will prevail. In Hegel’s case, will the new liberal French perspective, which Hegel supported, prevail, or will the old German feudal way of thinking prevail. For Hegel, this process is at the core of things, the struggle of ideas, so the dialectic is in the ideological realm. It’s a dialectic in literature, poetry, music, art, philosophy, theory. Marx then took that, and while he agreed, he said the real root of the dialectic is the contradictions in the mode of production.

So he took what was an idealist interpretation of contradictions, and said that these contradictions are materially based and embedded in a set of material relations, and in this case between the ownership of the means of production and the development of the forces of production. That then this concept is so Hegelian it has an ironic cast to it, for Marx argues that, quite unintentionally in the pursuit the developing capitalism and expanding it, the system itself lays the foundation for its ultimate downfall. Because there is a necessity in these contradictions in which capitalism necessarily develops in such a way that it also creates the political forces which will overthrow it.

For Hegel and Marx, this dialectical conception of history is a profound mixture of both a tragic and an optimistic conception at the same time. In other words, victory here is eventually won at a tremendous, unspeakable price.

On social wealth funds:

If one of the challenges to anti-capitalist action is that the left has no clear leader, perhaps a more significant one is that the left has no clear program. One example of a program the left might take up more broadly, as a way to propose rather than just oppose, is the macroeconomic management instrument often known as a “social wealth fund.”

Specific implementations of the general form differ, but the underlying idea is to challenge what we have already identified as the fundamental core of capitalism: private ownership of the means of production, through which labor is exploited. That exploitation is possible because the human heritage of innovation and increased productivity, which is ultimately the property of the public, has been stolen—that is, appropriated by capital. If the accumulation and increasing concentration of wealth is conditioned by this theft, it is further ensured by certain rights that have accrued to capital as a result of its power over the juridical apparatus. Any viable plan to socialize capital, to use capital for social purposes, must therefore involve encroaching on the rights of capital.

The social wealth fund encroaches on those rights and undermines private ownership by placing assets under the control of a public body. Very generally, firms are “taxed” in the form of stock, which is a representation of ownership, rather than being taxed in the form of currency paid to the state. Stock is a form of ownership, but also an asset that generates income through dividends. These dividends can be used to fund social services, which in some cases include universal basic income. The more significant intervention, however, is that a portion of dividends can be reinvested. In other words, dividends are turned into capital, but capital that is socialized since it is controlled by a public body.

There are, of course, many challenges to such a plan. Not least of which is that social wealth funds appear to be simply another technocratic solution to a fundamentally social problem. However, we should imagine these proposals as one way among many to build a movement by mobilizing people and engaging them in leftist causes, not as some ultimate solution. The term “social” obscures that social wealth funds have the potential to go beyond nationalizing or socializing assets. Rather, they are part of a broader struggle to subordinate capital. More problematic, however, is that in their current implementations these instruments often take the nation state as a given and so remain limited in their application to the problem of globalized capital. Since funds are modeled on taxes, they can only “tax” firms that are based in the country where the fund operates. However, funds can invest in publicly traded corporations outside their own nation-state, potentially extending their reach beyond these boundaries. The issue remains, of course, about who makes the decisions on which investments to make. Perhaps even more challenging is what happens when a national fund accumulates enough stock to significantly steer the decision-making process of multinational corporations. Given that the interests of nation-states are not always aligned, and given that national wealth varies widely among nations, such funds also have the potential to perpetuate certain inequalities in global decision-making processes.

Further information on social wealth funds: https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/projects/social-wealth-fund/

Concluding remarks:

The far right has won elections by speaking in nationalist terms, and speaking to the anger people feel over the last 30 years of living under a neoliberal agenda that has exported their jobs, cut their wages, and continues to minimize their social benefits. The established left in the US failed to acknowledge and admit to their role in the continuing detriment of their working population’s lives. Trump, on the other hand, mobilized this angry core.

Prof. Robotham stressed the significance of the current critique and attack of global capitalism coming from the right in U.S. politics, when it traditionally has been the left critiquing this global model. He sees the ultra right as pushing their agenda best, which happens to be anti global capitalism in many ways. The ultra right is leading a pushback against global capitalism, currently within the framework of traditional conservatism, but this looks like it could fall further to the right into an explicitly racist state, which would lead to a crisis in democracy.

In response to these strong forces it seems the left stands divided and unsure what to do. The usual liberalism defensive position has been “listen, it’s not as bad as you think, or as bad as they say.” That’s the stance Hillary Clinton upheld. That’s not going to cut it anymore. People are angry and the left needs to step up with a clear platform that connects with the masses.

Questions:

1. Marx’s dialectical and materialist conception of history helps us to think together the fundamental core relations of capital, which apply universally wherever a capitalist mode of production develops, as well as the deeply historically specific features of any particular instance of capitalism which emerge out of vastly different social and historical circumstances. But to what extent does Marx’s method of historical analysis, and the economic categories (such as labor-time) which inform historical and dialectical materialism, help us to understand non- or post-capitalist social formations? Is historical materialism a trans-historical social science or are its categories specific to capitalist societies? If the latter is the case, how might Marx’s conception of history be reconceived for a post-capitalist social order?

2. Professor Robotham stressed that the course of action of the left has to go beyond merely opposing the right. What economic proposals can the left present or utilize?

3. Another question this recent movement raises: Can a conservative, authoritarian project be fully realized within a bourgeoisie constitutional framework? (i.e. free press, free speech, freedom of assembly)

Hello all!

Thanks for the great summary of a through and thought-provoking lecture! I would like to think about Another question this recent movement raises: Can a conservative, authoritarian project be fully realized within a bourgeoisie constitutional framework? (i.e. free press, free speech, freedom of assembly)

I am not sure how helpful it is to relativize some of the terms here, but I think it is important to help us think through the relationship between the public sphere, a bourgeoisie constitutional framework and fascism.

One is that authoritarianism, like all political projects, is never complete. It will alway produce contradictions, have its fringes, its outsides. Additionally, it is always present for certain people at certain moments. Omi and Winant, for example, argue that the USA could best be characterized as a racial dictatorship for the majority of its history.

This reorients the question to ask: to what extent does the constitution (manifested here as a public sphere) deter fascism? Well, i’m not sure that it does. Outside of being evidence of the absence of fascism, I am not sure that freedom of speech necessarily produces anti-fascist politics. I am thinking of limits on free speech regarding Nazism and the holocaust in Europe. Or white supremacist marches in the US. This reminds me of the social wealth fund Don mentioned as a leftist economic strategy to reach large amounts of people and re-orient the economy. If they are controlled by some sort of popular assembly, how can we be sure that “the people” will govern ethically? I suppose that we can’t. In the same sense I see no reason that freedom of the press necessarily means an anti-fascist press. In fact, bourgeoisie constitutional frameworks may even be necessary for fascism, which involves a close state corporatism and therefore an idea of private propoerty, for example.

I would agree with the notion that a constitutional framework doesn’t _necessaraily_ deter fascism and freedom of speech doesn’t _necesesarily_ produce ant-fascist politics. But I’m not clear on why this is a question we should be asking? Is there any form of political organization that is inherently and necessarily non-fascist? Isn’t a political organizational form that categorically excludes one particular mode (even if that excluded mode is “fascist”) itself authoritarian? Certainly we can never guarantee that “the people” will govern ethically. We can’t be sure that a constitutional framework, bourgeois or otherwise, will never be deployed to institute a fascist state…but that doesn’t necessarily mean we should abandon those forms of government, does it?

Great summary.

I just wanted to piggy back on/agree with the first comment. Asking if an authoritarian project can succeed in a constitutional framework seems to be an odd phrasing. Fascist movements can flourish in such a situation, and should they be successful enough they can suspend any constitutional limits of their reach. This has been the case historically and bourgeois constitutionalism hasn’t provided any evidence that this has changed.

Thank you for the detailed summary!

Regarding question 2 (economic proposals that the left can utilize), I think ideologically cohesive yet historically/geographically-specific plans are key. Focusing on the particular yet common struggles facing people that are incurred by capitalist structures and communicating it as common, perhaps not necessarily branded by polarizing rhetoric like “anti-capitalist” would be pragmatic and strategic. I’m thinking here of strategies to preserve or appropriate land for the commons in expensive urban real estate markets. Because my point of reference as an individual and as a student is New York City, I’m sticking to what I know. Community Land Trusts, much like Social Wealth Funds, embody principles of redistribution and resilient future planning but operate within the strictures of market logic. But they offer tangible, meaningful benefits to participants–affordability and common control over land in perpetuity, protected from the market but appropriated from it. Its a strategic, political move in the party politics sense because it meets a need that is urgent and shared but it also subverts the very structure it operates in. Don spoke about Social Wealth Funds like a “Trojan Horse” and I think that’s a very apt and useful analogy. He also mentioned during our recent class discussion the importance of thinking about radical change as a series of transition phases–another pragmatic and helpful mindset. Even if a leftist party were able to construct a coherent platform and garner popular support, sweeping radical and immediate change is risky. Rebranding strategies as solutions to pressing and common yet geographically/historically-specific struggles could initiate a more resilient shift in the zeitgeist and deliver benefits more quickly.

I want to piggyback on the above commentary about the possibility for “ideologically cohesive yet historically/geographically-specific plans” which, like CLTs, can “embody principles of redistribution and resilient future planning but operate within the strictures of market logic.” Though, if I may, I would like to counter the idea that we should, first, consider “anti-capital” as merely strategic rhetoric and, secondly, that we must work within the strictures of market logic. It seems here is where we have to actually turn such ideas on their head. It is not that we must empty the concept of anti-capital — produce it as a empty signifier that is on profitable to the extent that becomes a floating signifier open to various demands — but rather we may consider anti-capital to name a particular approach and philosophy. I will refrain from rehasing my reading of totality in Marx’s writings, but I do want to note that it may profit leftist politics in the US to seize the opportunity that is before it today. That is, the opening of many people’s politics to an otherwise than capital. For me, I agree that CLTs are radical step forward in proposing viable alternatives which take seriously principles of redistribution, but must we confine them to the current logics of the market. David Harvey’s latest book, “The Madness of Economic Reason” provides a rather provocative treastise for our times, in it is a message which I have found compelling to many people on the street, so to say, and have witness crop up in even popular media. Take for example, this clip from ESPN’s “The Jump” about an elderly woman standing up to the local city council and demanding they stop negotiating with the owner, over the city paying $150+ million for renovations to Oracle arena – by the way the history of Larry Ellison, of Oracle, is worth learning more about. Notice that in the clip, the two men who provide commentary in support of the woman’s stance did not note the relationship between private enterprise and government. The host, Rachel Nichols, however, backs up the woman because what the people of Phoenix value and “important to us [Phoenix] as society, welfare for billionaires is not on that list… [paying for arenas] should not be a public burden. The public has enough other things to be concerned about.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_szoHw2tTs

Of course, I am not suggesting Nichols is expressing anything near to an anti-capital position, but her expressed ideas are indicative of many other instances in which the “madness of economic reason” is on the table, on the tip of people’s tongues. In Harvey’s book, I what pinpoints what troubles our current political imaginaries:

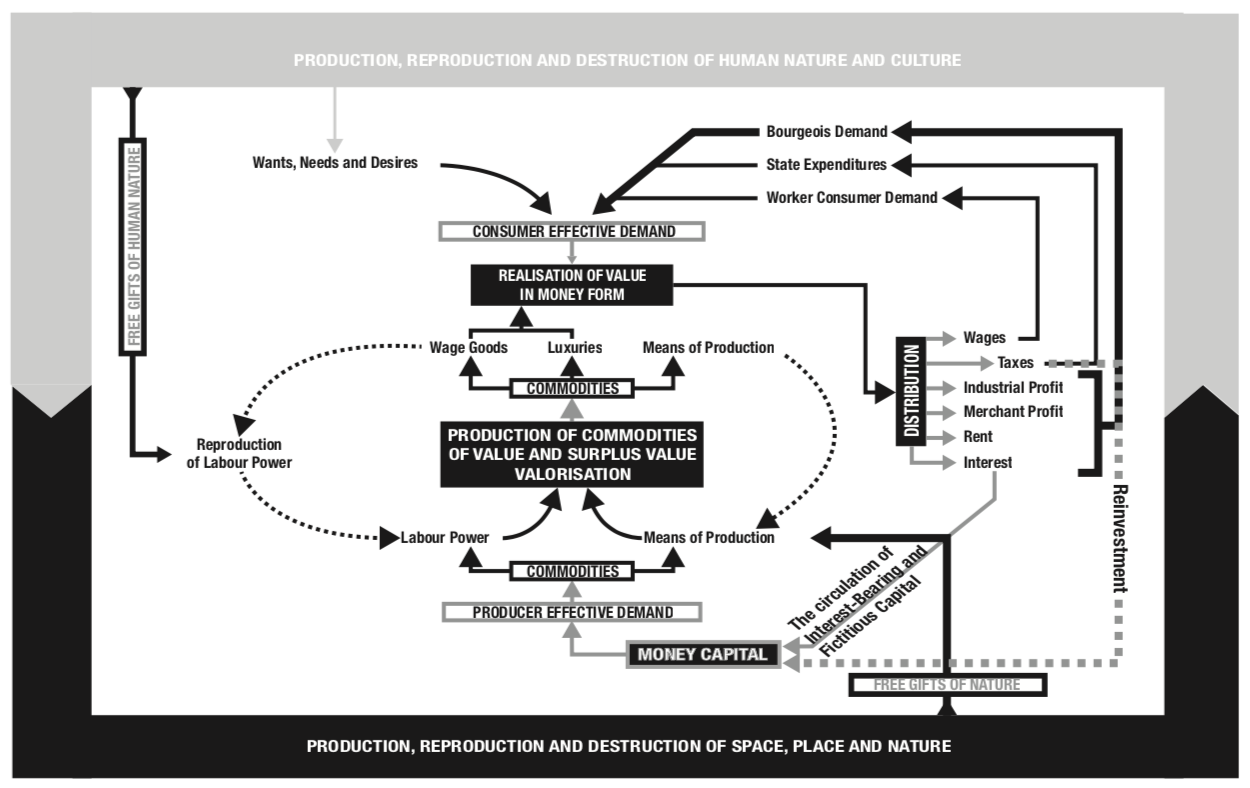

“In the same way that Marx invokes the idea of a contradictory unity between production and realisation from the standpoint of continuous capital accumulation, so there is a parallel need for anti-capitalist movements to recognise the contradictory unity of struggles over production and those waged around realisation. On the surface, the politics of realisation have a very different social structure and organisational form to that of valorisation. For this reason they are often treated on the left as entirely separate struggles with valorisation being prioritised as more important. Yet both sorts

of struggles are subsumed within the overall logic and dynamism of capital circulation viewed as a totality. Why would their contradictory unity not be recognised and addressed by anti-capitalist

movements?” (2017, p. 77).

While Harvey is here emphasis the need of anti-capital to contend with the Capital’s law of motion, I think we may tend to forget about the importance of logic. It may be because of my anectodal experiences in the US educational system in which I simply was not taught logic, in any capacity or form, during my schooling. So, perhaps, that’s why I found it so crucial to incorporate logic into my understanding even if I had to learn it didactically. In so doing, I saw logic everywhere: hydro-logical, geo-logical, ideo-logical, techno-logical, psycho-logical, eco-logical. But there does not seem to be an econo-logical; though I did find this curious article.

https://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/-econological-growth-110040900009_1.html

Instead, we speak of economics. The difference in suffix is telling, whereas -logical explains “that which comes from clear reasoning”, -ics describes instead “a body of facts, knowledge, and principles.” Can we say that David Harvey qua Marx has asked us to be econo-logical. What a weird neologism. Yet, it does point to a central contradiction of our time, the over domineering of economics and economy in our political system and social institutions but, somehow, the little understanding people have about what has so far constitutes the logic of the capital system – which in schools is synonymous with economics – and, thus, we have not been able to study (thus speculate) on what a logical economy might look like. I’m not sure dwelling in the humanities and social sciences is sufficient.

Thus, it seems like it is our job to anchor anti-capital, and its sentiments, to community, full life, and *love. Love is such a laden term, so I’ll take a moment here, and draw an outline. And perhaps, since we are writing from the context of academia, it might be best to take up what I consider the fallacy of one of its great, and now trendy, thinkers: Michel Foucault. For me, the fallacy of Foucault’s project was not what he has taught us about power/knowledge, biopolitics/biopower, and the like, but rather because his “critical criticism” does not leave open the possibility of a “third term” by which he could be critiqued. Critique, as Lewis R. Gordon notes, is, deeply, an act of love, a desire to fix an error so as to get it right, while critical criticism simply throws the baby out with the bath water. Foucault is especially troublesome because he was successful in demonstrating some of the key ontological impasses strangling our political machines in our current conjuncture, but he does so by framing his central concept, power, in an ahistorical and totalizing manner; the same holds true for similar continental philosophers (ie. Deleuze, Tristan) who want to think from a standpoint of the pure. The notion is rather silly from the outside looking in. Yet, this “new form will in any case be an asymmetrical one, in which we can identify a center and a margin, an essential and an inessential term” (Jameson, Valences, p. 19) can generate insights into workings of something like power. However, they are to immobile to be politically viable. They simply cannot speak about love.

Ok, so Karl Marx (1845) might help me make my point here, specifically his reading of Flora Tristan’s Union Ouvrière as anticipating the perils of critical criticism.

On one hand:

“Criticism achieves a height of abstraction in which it regards only the creations of its own thought and generalities which contradict all reality as “something”, indeed as “everything”… Flora Tristan, in an assessment of whose work this great proposition appears, puts forward the same demand and is treated en canaille for her insolence in anticipating Critical Criticism. Anyhow, the proposition that the worker creates nothing is absolutely crazy except in the sense that the individual worker produces nothing whole, which is tautology. Critical Criticism creates nothing, the worker creates everything; and so much so that even his intellectual creations put the whole of Criticism to shame; the English and the French workers provide proof of this. The worker creates even man; the critic will never be anything but sub-human though on the other hand, of course, he has the satisfaction of being a Critical critic… Criticism does nothing but “construct formulae out of the categories of what exists”, namely, out of the existing Hegelian philosophy and the existing social aspirations. Formulae, nothing but formulae.”

On the other hand:

“In order to complete its transformation into the ”tranquility of knowledge”, Critical Criticism must first seek to dispose of love. Love is a passion, and nothing is more dangerous for the tranquility of knowledge than passion… When love has become a goddess, i.e., a theological object, it is of course submitted to theological criticism; moreover, it is known that god and the devil are not far apart. Herr Edgar changes love into a “goddess”, a, “cruel goddess” at that, by changing man who loves, the love of man, into a man of love; by making “love” a being apart, separate from man and as such independent. By this simple process, by changing the predicate into the subject, all the attributes and manifestations of human nature can be Critically transformed into their negation and into alienations of human nature… Object! Horrible! There is nothing more damnable, more profane, more mass-like than an object — agrave; bas the object! [they say] … Finally, love even makes one human being “this external object of the emotion of the soul” of another, the object in which the selfish feeling of the other finds its satisfaction, a selfish feeling because it looks for its own essence in the other, and that must not be. Critical Criticism is so free from all selfishness that for it the whole range of human essence is exhausted by its own self…

The passion of love is incapable of having an interest in internal development because it cannot be construed a priori, because its development is a real one which takes place in the world of the senses and between real individuals… What Critical Criticism combats here is not merely love but everything living, everything which is immediate, every sensuous experience, any and every real experience, the “Whence” and the “Whither” of which one never knows beforehand.”

What Foucault does is simply change love with desire, and so there are critics who would rather talk about our desires (and passions) in the abstract. His critical criticism is enlightening, but often leads astray. Yet, I have noticed, in real life, colloquially speaking, that those invested in anti-capital struggle do not seem as articulate in expressing their movement as an act of love, in the most tangible and intersubjective manner. Instead, I have noticed a bit too much stoking of righteous anger, on the streets because it is profitable for numbers, and a bit to much critical criticism in academia. Let alone the extent our human ego tends to get in the way. This is a long way of saying, that it is in the spirit of critique that I would like to suggest we be anti-capital in how we speculate.

And so, in such light, and from this perspective, I do not believe any substantive change is possible if we first give into the notion that being practical means assuming “market logics,” especially the dominance of its current perversity in finance capitals.

Instead, it seems what is exciting about CLTs is that they offer the opportunity to bring in the particularities of community existence and relationships into the workings of politics, which is always historically/geographically specific, and peculiar. But since I am still learning about CLTs, I would like to make this point more explicit by critiquing what I noticed in the fights over minimum wage. But, in the need to be judicious with my time, I will include it in a discussion for another week.

Harvey, David. 2017. Marx, Capital, and the Madness of Economic Reason. Oxford University Press.

Marx, Karl. 1845: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/holy-family/index.htm

I definitely agree with Prof. Robotham’s read of Steve Bannon and other Rightists seriousness when it comes to presenting a program that aggressively addresses the current economic, fiscal, and social crises. I think there is a serious problem with a Left that lacks a positive (in the sense of a concrete alternative, not merely feel-good, though that wouldn’t hurt) alternative in its fight with these smart, serious, organized Rightists who are serious about building fighting coalitions that can win. Otherwise, fighting fascists and other right-wing solutions to social instability, without being able to present an alternative resolution, devolves into rear-guard operations that mix moralism and demands for patience among those—yes even the petty bourgeoisie—who are anxious about their future.

In Toronto, an open fascist named Faith Goldy campaigned against the Center-Right sitting mayor and his Centrist former chief city planner (the two main candidates for mayor) by arguing that the shortage of affordable housing, lack of homeless shelter space, and high rents were all caused by the presence of asylum seekers and undocumented people. Her program, eight times bolder than the two milquetoasts from the administration, would “solve” all those problems by expelling them from the city, cracking down on crime via stop-and-frisk policies, and thus Make Toronto Great Again. No counterexplanation of the problems, and thus no non-fascist counterproposals, really grew. She came in a distant third, with 25 000 votes, behind two people who could say nothing but that things were more or less fine, and that the issues didn’t need real addressing. A distant third is nonetheless third, and excluding her from debates and election broadcasting, as happened this time around, will be impossible in the future.

I’m deeply skeptical of social/sovereign wealth funds as anything but an extremely partial step toward a socialist project, but thinking on this scale—large-scale alternatives to the current mess we’re in—is exactly the right direction. One was used by Québec’s developmental state from the 1960s onward, but likewise has a fiduciariy obligation to provide returns for all of the state insurance funds and pension contributions that paid into it, and so its projects need to produce a return (someone getting exploited or expropriated somewhere) in order for it to not turn into sheer state expenditure. Nevertheless, offering these counterproposals with the same ambition as Bannon and Goldy will be necessary to give an alternative to the fascist solution to crisis.

I would like to respond briefly to question 1: Is historical materialism a trans-historical social science or are its categories specific to capitalist societies? The question reminded me of a statement Terry Eagleton made in the first chapter of Why Marx Was Right that “Marxists want nothing more than to stop being Marxists.” In this regard, Eagleton positions Marxism, a term he uses, as a provisional affair with a definite ending (i.e. the end of capitalism).

Of course, the end of capitalism may mean the end to specific categories of analysis Marx created and/or utilized to better grasp the workings of the system as a whole, as you suggest in your question, but I think that it’s important to understand dialectical materialism (DM) as a science of the world that goes beyond simply allowing for a critique of capital. Immediately, I’m reminded of Christopher Caudwell’s application of DM to an examination of love in Studies in a Dying Culture as well as Engels’ usage of DM to explore nature in Anti-Dühring. While criticisms can (and certainly have been) made of the application of DM in these works, I think they still go a long way to demonstrate DM as a science that attempts to abstract categories from material reality that is understood to always be in a state of constant change, meaning that these abstract categories also need to be revised or removed if they prove no longer adequate to a specific context. Regardless, these works show DM as a methodology with far more reaching applications than simply to critique capitalism.

Therefore, while categories such as “labor time” may no longer be useful in a post-capitalist economy, particularly due to its current relationship with value in capitalist economics, there’s no reason why DM would not still be in play—why Marxists would no longer need to be Marxists.

And them’s my ten cents!

In agreement with the first two comments, and due to the fact that our constitutional amendments are enforced by interpretation, it would not be a far-fetched notion for fascism to arise in a bourgeoisie constitutional framework. Actions of governments and judiciary decisions are all subject to interpretation and bias depending on the individuals or group of individuals that hold decision making power. Because of this even largely democratic governments can shift towards an authoritarian model (ex: current White House administration) and eventually overtaken by fascism.