[lead bloggers: Laura Rivas Burgos, Roberto Elvira, and Nicolas Benacerraf]

In this week’s lecture, David Harvey reflected on Marx’s value theory, which is often mistaken for the “labor theory of value” discussed by classical economists. While Marx did engage the “labor theory of value” to formulate his own ideas around value production, he did so in a critical spirit and from a point of contention.

In order to explain how Marx’s concept of value works, Harvey revisited the six introductory chapters of Capital, Volume I, where Marx observed that the process of commodity exchange is facilitated by a common social standard of measurement (money). More precisely, different use values suddenly become commensurate in exchange under the larger umbrella of value. David Ricardo had previously equated value to congealed labor time, but Marx would distinctly qualify this statement to affirm that value is *socially necessary* labor time. As such, value is not simply a quantitative expression, or intrinsic, but is actually contingent on a series of social processes tied to the spheres of production and circulation where value is realized.

Value can only exist in a society where commodity exchange has become normalized, which in turn requires the existence of money to facilitate such exchange. Money is value’s form of appearance; a material representation of value that quantitatively expresses it, as well as a vehicle for its realization. But price and value are not the same. Whereas Ricardo was concerned with the former, Marx understood the potential incongruities between these two concepts and (in Volume I) was more interested in the consequences of value production for the worker. As such, his analysis transitioned into the production phase to better grasp how value is constituted through material activity.

The “coercive force of competition” compels capitalists to implement certain practices in the production phase (e.g. the extension of the working day) in order to maximize surplus value. Similarly, in order to boost relative surplus value, capitalists introduce cooperation, the division of labor, technological innovations, and so forth. Some of these measures eventually affect the organic composition of capital. For instance, technological innovations may result in an increase of constant capital at the expense of variable capital, reducing the proportion of labor power involved in the production process. The release of workers contributes to the formation of an industrial reserve army—a mass of potential workers living in immiserated conditions of social reproduction. This surplus of labor power fulfills the important role of keeping wages low, thus yielding more surplus value for the capitalist. As such, value as it is conceived in the market is constantly being revolutionized through modifications at the level of production and at the expense of the worker. Marx’s distinctive value theory expresses the contradictory unity of the labor theory of value (exposed in the first 6 chapters of Capital Volume I) and the “value theory of labor” (as Diane Elson calls it) in the sphere of production. In many ways then, Harvey suggests, the theory of value is also a theory about the conditions of the worker; a theory of the alienation of workers from the fruits of production.

This interpretation of the value theory illuminates certain contradictions within the process of value production. This takes us to the second section of Harvey’s lecture, concerning the falling rate of profit. In Capital, Volume III, Marx explores how labor-saving technologies have a tendency to reduce the overall surplus value. That is, a decrease in labor input also results in a falling rate of profit because workers are the ones who actually produce value. However, commodities need to be sold in order for this value to be realized. This dynamic introduces a contradictory relation between competitive market processes that seek to yield more surplus value and the miserable conditions of social reproduction that these processes produce. That said, although the rate of profit is prone to decrease over time, the overall mass might still increase. And the proportion of profit that is allocated to the capitalist class also increases, producing a growing income disparity. There is a fundamental disconnect between the conditions in which value is produced and the conditions in which it is realized. Poor conditions of social reproduction drive consumption power down, leading to a crisis in realization. Again, this is an instance where we can observe that the capitalist experiences alienation. Here, alienated social power manifests itself and confronts society as an autonomous social *thing* that exists above and beyond the individual participants of all classes.

The regularity of market crises – momentary violent solutions that restore balance to the “limit cases” of capitalism – expose the inherent limits and contradictions of capitalist organization. To overcome those limits, the markets expand. Marx anticipated the building of a world market, which he called the destiny of the Bourgeoisie (Communist Manifesto). Only through the realization of surplus capital can crisis (“realization barriers”) be overcome, and this realization takes place in the act of consumption (be it final consumption or productive consumption). Accordingly, the increasing insufficiency of local or national realization obliges the expansion of capital on a global scale. The crisis of 2007/2008, which sprung in the subprime mortgage of the real-estate in the southern USA, was resolved through the productive consumption of China, which through infrastructural investment broke the barrier of realization by absorbing the surplus of capital and labor circulating at that time.

Discussion Questions

1) Harvey mentioned that crises in capital do not represent endpoints, but violent solutions that restore order to existing contradictions. In what sort of situations could these crises and contradictions represent – if not an endpoint to capital – at least a threshold for articulating anticapitalist thought and action?

2) In Capitalism, price functions as a representation of value, offering a material substitution for an abstract/immaterial concept. Part of the job of anticapitalists is to articulate the alternative forms of value that are excluded from the capitalist model. What are some examples of movements, actions, or authors that reveal other alternative forms of value? Might this relate to the prospect of inventing “socialist money”, which Harvey alluded to during the lecture?

3) Alienation is both a condition of the exploited as of the exploiter – of the laborer and of the capitalist. However, how do these forms of alienation differ? Is it enough to state that one is of the production and the other one of the realization process? If alienation is an integral part of the capitalist system, and if time (when) and space (where) class identity (who) are also a part of it, what role does context play in the experience of alienation?

4) We will post summaries of the questions that were asked in person during the lecture. You might choose to continue one of those threads.

The growth of Death; Madness of the economic reason

I would love to share with you what I’m doing with our Anti-capitalism public seminars. I’m interested in transferring the experience and lectures of our “Anti-capitalism” seminar into colloquial Arabic of Cairo, by publishing a reading (we call it a digest) of the public lectures of the seminar in colloquial Arabic on a website that a friend and min founded 4years ago.

This colloquial ‘digest’ of the pro-seminar with it’s lectures and debates comes as part of a ‘movement’ in Cairo that aims to disseminate contemporary critical debates in social sciences among Arab young scholars and interested audiences at large.

the case of colloquial Arabic in Egypt is quite significant. Arabic (official Arabic) have been used, for at least the last century, as a tool to dominate culture among specific classes. The majority of the population cannot deal with official Arabic. Only people with a high university degree can deal with- or even struggle with – this official version of intellectuals’ and politicians’ Arabic. Our aim at our website is to afford the most recent debates on critical humanities in the language of the culturally margenalized people. (to make the picture more clear it is important to notice that many progressive languages’ specialists consider what we call “colloquial Arabic” to be an independent language – as long as it has its own grammar with a different understanding of time – and not only a colloquial version of Arabic).

The website grew to reach 30 thousand followers who are interested in Humanities in general and Anthropology in specific.

I consider this movement of translating into colloquial Arabic to be part of capitalism resistance and class domination of knowledge.

I’m not sure if anyone in the “Anti-Capitalism” group here might know Arabic or colloquial Egyptian Arabic, however, I am sharing it with you in case you might find this experience to be useful for you in your own context.

The title of the first public seminar in Arabic is :

The growth of Death; Madness of the economic reason

here is a link

https://qira2at.com/2018/09/10/david-harvey1-economic-reason/

Super cool idea!

With regard to alienation: I feel included to suggest that from the perspective of anti-capitalist thought and action, we should be more focused on alienation as experienced by workers in various contexts. While capitalists are certainly also alienated from work in various ways, it is their disproportionate closeness to manufactured surface values relative to the laborer that I view as most important.

That is, when we as anti-capitalist actors engage in recruitment, unionization, or political efforts against the capitalist mode of production, we should be more focused on communicating how workers are alienated from wealth they are producing. From this perspective, I think the context (specifically the “where” and “when”) of alienation as it affects workers is the most important topic to explore.

With this in mind, how can we communicate workers’ alienation from surface value in a contemporary context?

I agree with Anthony to a point. I think understanding how workers experience alienation at the point of production is very important for the development of political consciousness and for solidarity building. Of course, the theory of alienation/estrangement needs to be expanded a bit here to also encompass workers in the service industry, which Marx did not deal with in Estranged Labour or Capital.

That said, I think considering how capitalists might be alienated within the social process of production is interesting, as well. I mean, Marx wrote that workers under capitalism are alienated from their “species being.” In this way, capitalists can be said to experience the same, as they too are alienated from their fellow man and placed into competition. However, the consequences for the worker are much more dire.

In a way, though, thinking about how the capitalist is alienated from capital, as well as the capitalist economic system, at least gets us away from simply blaming the ills of capitalism on human greed. Understanding the contradictions between the profit motive, the driving down of wages, and the need for surplus value to be realized within through commodity consumption, gives us a real sense that the system is the problem. This means no form of altruistic reform will necessarily alter its internal contradictions. It ain’t an issue of simply getting rich folks to act right, feel me?

I also think it is important to think about alienation, and to emphasize the experience of the worker , rather than that of the capitalist. When we speak of how a worker experiences alienation from value and the product they produce, we are implying a certain right that this worker would have to the fruits of their labor. Speaking of alienation of a capitalist from wealth upsets this and erases the issue of exploitation, or, the process y which a capitalist takes excess value without producing it. By talking about “alienation” in both situations, we are reducing the political import of our vocabulary.

Additionally, I wonder how much we need to communicate to workers about alienation. Even the idea of us communicating to them reasserts so many problems already known to organizers. Poor people are generally well aware of their poverty. Rather than fomenting awareness of the contradictions of capital, helping people organize and address their concerns could be more effective for recognizing the embodied experience of being a worker. Some times discontent is manifested against racialized workers, and in this case a focus on exploitation can be useful in understanding the circulation of power and how activism should intervene. However, this does not seem like an issue that workers need “us” to teach them about. Rather it speaks to the necessity to combine race and class analyses in our anti-capitalist thought and action, including in OUR union.

Thank you for your summary and relevant questions.

I’d like to concentrate on the second question, on how to visualize alternative forms of value that are (or at least would seem to be) excluded from the capitalist model. According to Harvey’s perspective, value cannot be reduced to the average number of labor hours required to produce a commodity, as it would be defined by labor theory of value. Instead, value is an abstract result of social relations that take place in the process of its circulation and production, in which social reproduction and surplus value extraction are necessary parts. In Harvey’s words, “Value becomes an unstable and perpetually evolving inner connectivity (an internal or dialectical relation) between value as defined in the realm of circulation in the market and value as constantly being redefined through revolutions in the realm of production”(1). It Is by keeping in mind the interconnectivity between competitive market processes, surplus value production and social reproduction that we can make sense of the perpetual evolution of value and of the contradictions inherent to it, one of them being the contradiction between the need to perpetually expand the market through consumption and the deteriorating conditions of social reproduction that comes with it.

As I see it, this way of understanding value as an interconnected abstraction of social processes is a lot more helpful than the labor theory of value in accounting for the conditions for the reproduction of capital beyond labor. From this perspective, the free gifts of nature and of social reproduction that were seen by many as absent from Marxist value theory as it was generally understood, find a really important place in the production of value (even if Marx didn’t go in to the details of how this happens), and are also places where the crisis of capital and the emergence of anti-capitalist action might take place, as some of you have already noted in the previous blog posts and responses.

Also, this somehow “extended” understanding of value might give a better account of how value circulation works in the 21st-century post-fordist knowledge economy, although I’m not sure how. For a while I have been struggling to find the relevance of Marxist theorization of value to make sense of production processes that are mostly computerized and immaterial, and that seem to rely more on the production of knowledge and data than on waged labor. I was concerned, for instance, after listening to Harvey’s first lecture, on how the participation of consumers through social media in the valorization of Brands (another form of immaterial capital) could be theorized from a Marxist point of view. If those interactions, however voluntary, produce value, shouldn’t they be considered as a form of fetishized labor? Some theorists have apparently taken this line of argumentation, by stressing the hidden exploitation that is behind those processes. This, however, would be based on the assumption that only labor is capable of producing value, and that knowledge can in itself be a source of it. Marx, however, was explicit in saying that Knowledge (and affect) cannot have any value in the economic sense since it is a non-rival and nonexclusive good (Ouellet,2014:27).

In this context, I guess that the question which I’m trying to make is: In which way is knowledge and affect contributing to the production of value in post fordist capitalist economy and what would be their place in Marx’s value labor theory?

Maxime Oullet tries to give an anwer to this question in the following article,which I really recommend all of you to read:

Ouellet, Maxim (2015) Revisiting Marx’s value theory: Theory of immaterial labor in Informational Capitalism.

(1) Harvey, David (2018) Marx’s refusal of the Labor Theory of value. http://davidharvey.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MARX%E2%80%99S_REFUSAL_OF_THE_LTV.pdf

“If money is the bond binding me to human life, binding society to me, connecting me with nature and man, is not money the bond of all bonds? Can it not dissolve and bind all ties? Is it not, therefore, also the universal agent of separation?” (Karl Marx, Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844)

Regarding question 2, I would like to share with you the experiences of some Catalan cooperatives that try to use alternative currencies to the Euro. I got to know these initiatives following a talk given by Enric Duran during the M15 movement in 2011. Enric Duran is an anti-capitalist activist who leaved Spain in 2012 and since then has been in hiding because he is accused of “robbing” 39 Spanish banks and nearly half a million Euros as part of a political action to denounce the capitalist system. In fact, Enric asked for 68 different loans to 39 financial entities with the most diverse excuses: buy a car, reform a house, etc. He also created a ghost company and falsified some necessary documents to justify income. In this way, the Spanish credit control system did not detect his indebtedness during some months. With the money he got he financed social movements and kick off the degrowth movement in Catalonia.

Enric Duran’s main argument is that commercial banks create money in the form of bank deposits by making new loans. For example, when a bank makes a loan to someone who signs a mortgage to buy a house, usually the bank does not give thousands of dollars in bills. Instead, it credits a bank account with a bank deposit for the amount of the mortgage. At that time new money is created. Enric Duran believes that robbing banks asking for loans that will never be returned is not stealing the savings of ordinary people, but directly attacking the logic of money generation.

One of the initiatives carried out by Enric Duran with the money taken from the banks was the Catalan Integral Cooperative. The main objective of this cooperative is to cover all the needs of its members – food, housing, employment, health, education, social protection and transport – by progressively cutting ties with the capitalist system. The Integral Catalan Cooperative uses its own social currency, the EcoCOOP. This currency is accepted in all Catalan eco-networks and many Spanish social currency networks.

One of the purposes of these alternative currencies is to strengthen the community’s social ties through the construction of strong socio-economic networks within small territorial spaces such as neighborhoods or small municipalities. They are currencies that do not generate interest or inflation and they cannot be stored nor are scarce (there are mechanisms to avoid them). In turn, local currencies try to avoid the flight of “capital” to the outside of the communities by not having value outside of them.

In any case, in relation to what we have seen in the previous lectures, Enric Duran’s action and the functioning of the so-called social currencies, some doubts have arisen and the truth is that I wonder if someone could answer or recommend me readings about it.

In one hand, Marx stated that the value of a commodity is determined by the amount of necessary social labor to produce it. This socially necessary work refers to abstract human work, that is, the human physical and mental effort expenditure, regardless of the concrete characteristics of the work. The main theoretical conclusion derived from this is related to the source of profit, that is, that all profit is surplus value and all surplus value is worker’s unpaid work (this is a theory about the social nature of profit centered on a commodity, not a proposition about the determination of prices, neither a theory that takes the social set of all the commodities).

When a commodity is sold above its value, it appears as if the exchange were the source of the profit, as if it arose from the excess of the price over it. However, Marx also concludes in Volume III that when a commodity is sold above its value, another or others are necessarily sold below it in an equivalent magnitude. Any individual gain that emerges from the exchange is exactly equal to the losses of another individual in another exchange. That means that society as a whole does not win with exchange or trade, and again, new value is only generated with human work.

On the other hand, in David Harvey’s text that Leo has shared, is stated that “market can only work with the rise of monetary forms that facilitate and lubricate exchange relations in efficient ways while providing a convenient vehicle for storing value. Money thus enters the picture as a material representation of value”.

My question is how, where and when the different logics are related. I mean, we have the generation of value through human work, money as a representation of value and as a lubricant of exchange relations, and the generation of money by commercial banks. It is clear that the generation of money is not proportional to the generation of value and that since Nixon broke with the gold standard money is the only form of capital that can increase without a physical limit. However, somehow the generation of value through work should be related to the generation of money. They cannot be absolutely independent. How are they related?

Enric Duran made an action to draw attention on the banking system and the generation of money. Beyond noting that half a million euros does not tickle the banks, how can we stop banks’ speculation and accept Marx’s statement that the bankers are necessary to create the money that lubricates the exchanges?

Finally, social currencies such as the EcoCOOP serve to reinforce the social bonds of a community. There is a series of goods and services produced within those communities that can be exchanged with those currencies. However, a large part of the goods we consume are part of the global market and those cannot be bought with those local currencies. My question is whether local currencies can attack the generation of national money and the global currency markets, or if on the contrary, if the only way to attack those logics would be taking control of central banks.

I did a bit of looking into the stunt by Enric Duran, and it’s rather interesting. Duran took out a series of loans from European banks totaling somewhere in the neighborhood of 500k Euros. These loans were made based on inaccurate reports that Duran made of, among other things, the purposes for the loans. He may also have inaccurately reported his income etc. but here that’s not the interesting point. In any case, the loans were fraudulent, which Duran not only admitted but publicized quite widely.

My understanding of it is that Duran’s stunt was deliberately undertaken in order to reveal the imaginary quality of capital creation and the ideological assumptions that underlie it. The loans were made based presumably in part on what Duran reported in terms of his income and wealth, but they were also made specifically for certain purposes: they were car loans and loans to start traditional businesses, for example. But Duran gave the loan proceeds to leftist social organizations: community gardens, worker cooperatives, housing initiatives, etc.

The interesting part, however, is that Duran then revealed that these loans were all fraudulent, that he had no intention of repaying them, and that he wanted the banks to pursue legal action to recuperate their funds. But because the loans were made by several banks and were each for relatively small amounts, the banks essentially are not interested in pursuing the recovery of their money. Duran’s point, as I take it, is that banks are essentially interested in making loans for particular purposes, but that on a case by case basis the repayment of any specific loan is not among their top priority. In other words, they generally want their money back, but the money isn’t the most important thing. The most important thing is creating debt that serves particular ends, which are the accumulation of capital in the form of the profit made by firms and the accumulation of wealth in the form of property. When banks make loans they consider the probability of repayment, but they also implicitly consider the ideological motivations of the loan. They make loans based on a particular system of values—some of which are risk and reward, but some of which are also inherently social. And if they’re willing to cut their losses in the case of small loans, there is essentially no financial reason for them not to make loans similar to the ones Duran got, although the justification is often given as the lack of ability to repay. But the underlying reason not to make such loans is that they are at odds with certain ideological purposes that banks in fact are most interested in.

In Capitalism, price functions as a representation of value, offering a material substitution for an abstract/immaterial concept. Part of the job of anticapitalists is to articulate the alternative forms of value that are excluded from the capitalist model. What are some examples of movements, actions, or authors that reveal other alternative forms of value? Might this relate to the prospect of inventing “socialist money”, which Harvey alluded to during the lecture?

In response to Question 2, I’d like to discuss the contradictions of capitalist production that yield negative externalities. These externalities can also be considered “hidden costs” of production or consumption, and their consequences tend to lag behind actual realized consumption/production or be well-hidden. I suppose that any production or consumption pattern inherently produces externalities, and they are absorbed differently in the social economy. A simplistic example is factory-farmed food, which, although extremely market-efficient and high-yielding, decimates the soil in which it’s planted and essentially encourages unmitigated consumption of natural goods. Innovations in agricultural technology have enabled farmers to continually wrest yields from the same fields (and animals), but the concomitant production methods (fossil fuel use, high concentrations of antibiotics, declining nutrient levels, to name a few) produce compounded externalities. “Buy local”-type advocates and activists make claims that traditional agricultural methods, combined with proximity (to limit oil consumption and reduce air pollution), are superior and have these external costs built into the price of locally-sourced organic foods. It’s a problematic model (thanks to the social identity it contributes to for bourgeois class cultivation), but I think it is adequate for rhetorical purposes. Would accounting for externalities in the “natural” price reveal the true cost of a commodity? When it comes to labor, the hidden externalities are usually off-shored and covert– there are endless examples, but a few that come to mind are extractive mining (diamonds) and textile sweatshops. Campaigns to lessen the hostile exploitation of these workers petition for raising the prices of these goods in order to improve their wages and working conditions. Would pricing for externalities effectively be a form of redistribution?

I’m not entirely convinced by the above arguments on choosing the form of alienation (proletarian or capitalist) to “emphasize.” In Marx’s understanding of capitalism, both are true. As people have emphasized, the worker is alienated from the means of production, the product of her labour, the surplus value she produces, and control over her labour process—not to mention the good life more generally. On the other hand, individual capitalists produce for profit in a market over which they have next to no control: the coercive forces of competition mean that a particular capitalist faces objective pressures from competitors with better techniques, more exploitative practices, longer working days, “uncosted” or “unvalued” externalities (on Emily’s point), lower outlays on wages and benefits, etc. It’s important to remember that in capitalist competition, profits aren’t just a fund for luxury consumption. Capitalists must regularly reinvest a large portion of those profits in order to keep up with the competitive standard in their industry, or their firm will go to the wall once it can’t recoup costs plus profit at a dropping prevailing price in the market.

Whether these individuals are fulfilled or stressed, sure, is not all that interesting. But for me, understanding the alienation of capitalists under capitalism is not a question of whether we “feel bad” for the capitalist; it’s of understanding what the actual range of their margin of maneuver is. It’s about understanding that capitalists don’t do bad things because they’re bad people (though plenty of them are), but because these are the rules of the game, which allow some playing around but only within strict limits.

In social movement studies terms, it is important to have a clear picture both of the “disruption costs” that worker action would lay on the employer, and the “concession costs” the employer would have to pay to meet the workers’ demands. Determining the extent of both of these sets of costs, particularly so that the cost of a strike outweighs the cost of settling it on the workers’ terms, is a crucial strategic question for those of us serious about fighting to win. And they apply well beyond a simple contract dispute; this counts no less for people who want to completely transform the way we organize the reproduction and production life and the means of its sustenance on this planet, away from one where the creative-destructive norm of value throws people and places in and out of the good fortune of even getting to be exploited.

Of course employers and politicians regularly insist that there is “no money” for even basic social-democratic demands, while military and policing budgets inflate, and critics of capitalism should be able to asses to what degree (given that these institutions still operate in a capitalist society) that is really true. Raising wages in a sweatshop or a farm operating on a razor’s edge of profitability may, given the structures of outsourcing and supply, actually drive it out of business, leaving people desperately fighting to even be formally exploited. It’s a common refrain from neoclassical defenders of sweatshops, but (just like Adam Smith and Ricardo), they’re describing a real phenomenon, even if from a silly perspective.

We need to be serious about whether the specific targets of our organizing are in a position to even be forced into giving us what we want. The mere fact of righteously fighting exploitation cannot substitute for an informed strategy. Otherwise we may waste a great deal of our limited organizing energy on defeating opponents who don’t really have the power to deliver what our action has been aiming for. All that organizing time and consciousness-building coming to nothing, or less than nothing, can be a deeply alienating experience.

I think we can connect this question of the alienation of the capitalist and the alienation of the worker to the role of money as a universal equivalent, and exploration of what socialist money would look like.

As others here have pointed out, both capitalists and workers are alienated, but in different ways. Marx says more about this in the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, but the main thrust of the analysis is that workers are alienated from themselves (exploiting their own bodies and minds in the production process), the product of their labor (the commodity), from each other (interactions with others mediated by commodity exchange), and from nature (existing in a world created by capital). Alienation of this type does not define existence for the capitalist. Capitalists are forced by the rules of the market to behave in a certain way to stay in business, but this is in no way comparable to the forms of alienation that workers experience under capitalism. I suppose you can find “romantic” anticapitalism amongst capitalists who are dismayed by the profaning of existence by the rise commodity exchange as the ordering principle of human society, but Marx was rightfully dismissive of the romantic bourgeoisie as a force for social transformation.

The alienation experienced by workers is for the most part a result of the commodification of their lives, which occurs in concrete form and can be concretely resolved. Workers experience commodification in three ways:

1) The need to sell their own labor to a boss for money, a result of the dispossession of the working class from the means of production or the pre-capitalist “commons.” The threat of unemployment becomes the foundational economic reality of working class existence.

2) The consequent hierarchical organization of the workplace to allow the boss to squeeze as much surplus value as possible out of workers. This entails the ability to hire and fire, set wage rates, assign and supervise work, and determine what is produced and how it is produced.

3) The compulsion or workers to use wages to purchase back the products of their labor.

These are the three pillars of capitalist society as experienced by workers. At various points in history, socialists have attempted to knock down one or all of these pillars, in particular locations or universally. The boldest attempts to break with the foundations of capitalism were in the states that were taken over by socialist and Communist parties in the 20th century.

Although each state was a bit different, in the “really existing socialism” of the former Soviet Union, the state owned the means of production in a sort of “trust” for the working class. In China, the state gave control of land and some factories to local communes and cooperatives. The capitalists in these states were expropriated, sometimes with compensation, sometimes without compensation. In China, the CPC gave capitalists who remained in the country after 1949 a state pension and encouraged them to stay to help build socialism. Pretty nice of the CPC. But the main focus of course was on changing life for the working class, guided in large part by Marx’s theories of capitalism, and in surviving attacks by western capitalism.

In these socialist systems, all were required to work, and in most cases received a wage, but the relation was constrained by strict laws around what workers were entitled to and what state managers could do, and culture that celebrated workers as the masters of the factory. For example, the workplace had managers, but they had extremely limitability to set wages or hire and fired, which gave workers far more power in their daily lives. Everyone had the right to a job, so the threat of starvation and homelessness was absent. By the same token, the promise of getting rich through exploiting others was also absent. Under state socialism. distribution was not primarily organized through a market, but rather through lottery systems or planned, relatively equal distribution through waiting lists. Most systems of state socialism included some form of “Iron Rice Bowl” guarantee of the necessities of life for all. The state’s planning system was oriented toward production of use values for the working class– apartments, clothes, food, etc. Ironically, in the popular consciousness state socialism is widely seen as less efficient at producing and distributing these necessities than the capitalist West, although that perception seems to be changing as the realities of 20 years of neoliberalism have set in in the postsocialist states.

Money existed in all of these socialist systems (the East German 100-Mark note had Marx on it, what would he think about that? https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_(DDR)), but as far as I can tell, it could not be accumulated as capital to be invested or used to exploit others’ labor. In other words, money was not a universal equivalent under socialism. Some things could not be bought and sold, or could only be bought and sold under strict regulation (such as labor, housing, cars, etc.). If state socialism attempted the decommodification of most areas of human activity, we could say that Neoliberalism is the exact opposite– the commodification of everything.

How would Marx analyze these systems? Is state planning and the limited use of money as a tool for exchange/distribution a true rupture with the value form under capitalism? Is there a better way? What can an anthropological look at societies that have not had capitalist economies tell us?

The role of local currencies seems very different from the role of money in the socialist states. In most cases, local currencies seem to be tools for allowing a local bourgeoisie to isolate itself from the world market and competition with multinational corporations. For most of these currencies, there seems to be little in place to prevent them from being accumulated and used as a form of capital, albeit only in a local, circumscribed market.

Since there is already a fruitful discussion around question 2, I would like to veer into question 1 and reflect on the window of opportunity that crises are able to bring for an anti-capitalist world to come about. While natural phenomena certainly represent an onslaught to capital accumulation (especially in the context of climate change), here I would like to touch on those kind of anti-capitalist actions and contradictions within capitalism itself that able to give way to transformative crises.

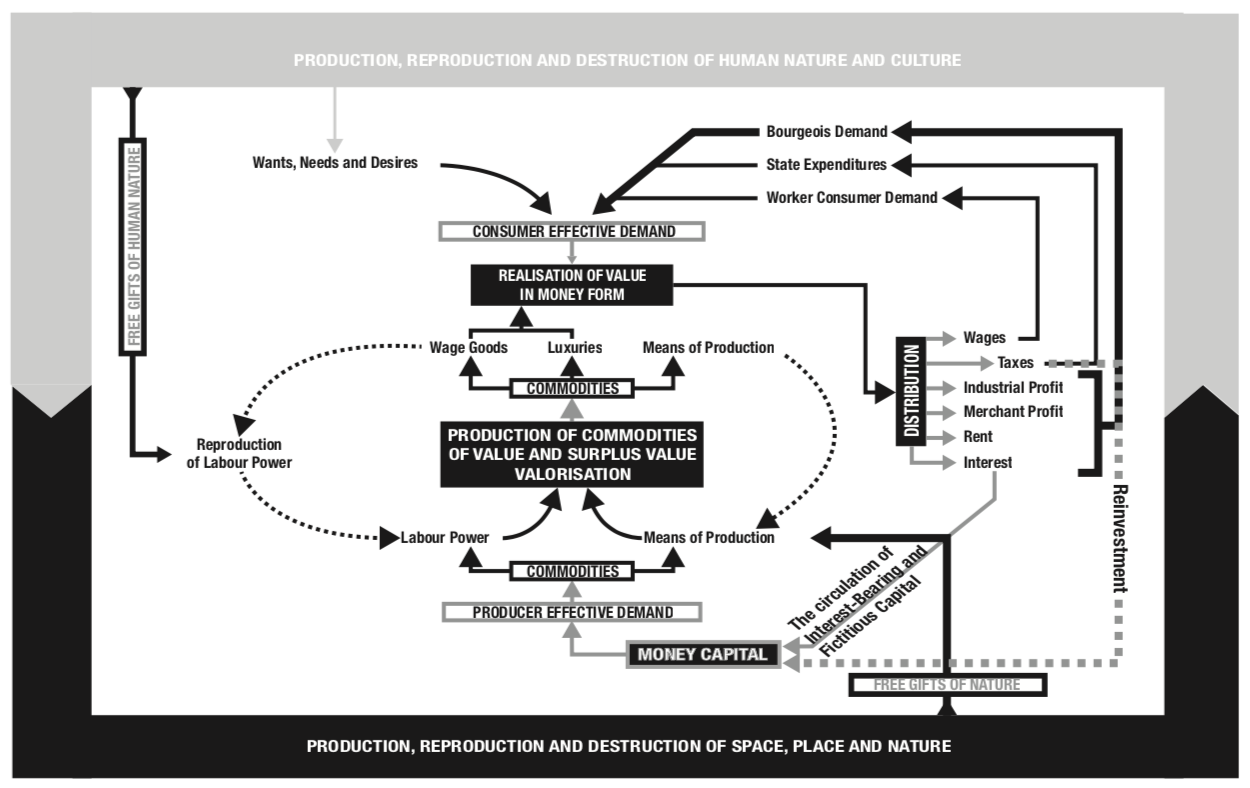

In Marx, Capital and the Madness of Economic Reason (2018), Harvey argues that visualizing capital as an organic totality is of central political relevance insofar as it enables us to determine the real extend of crises and evaluate the possible success of anti-capitalist actions and proposals. While in the three volumes of Capital Marx delved into the workings of capitalism, he did not provide a holistic theory of capital as an organic totality. What we have seen in the seminars is instead a map of capital flows (the circulation of capital as a whole) which aids us visualizing how this totality might look like. Although the different moments within this circulation are loosely coupled with one another, Harvey reminds us that the different phases of capital (valorization, realization and distribution) presuppose each other and are all subsumed within the totality (2018, 45). In this light, transformative actions and crises would be those that are able to make an impact on capital in its organic totality. Thus a central question is: what are those social struggles able to resonate into the organic whole provoking a crisis that puts real and cross-cutting barriers to capital circulation?

Harvey is clear in exposing how certain political proposals that may seem to be revolutionary are actually not grounded in an accurate understanding of capital circulation and, therefore, end up benefiting the status quo/the capitalist class. One example is the demand for establishing a minimum wage (which is typically part of the political program of the left in many countries including the US – it was included in Bernie Sanders’ primary campaign). Harvey posits that while this measure aims at improving the quality of life of the working class, it ignores that there is appropriation of value taking place in the realization phase (2018: 47). For instance, different companies strategically raise the prices of the products they sell and banks do the same with their interest rates, which prevents workers from attaining better access resources. In fact, that is why many capitalist firms are actually in favor of proposals such as basic income since they know that their products could not be sold if their potential buyers had no income. A visualization of capital as an organic totality enables us to discern more clearly those actions that are (wittingly or unwittingly) maintaining the circulation of capital from those that are able to transform the system by putting tangible barriers to capital accumulation.

Laborers not labor, alienation and fetishism of production

I think it is important to emphasize that “alienation” is not only from the final product and its surplus value, but first the alienation from oneself and other surrounding workers (humans).

Althusser, in his significant introduction to his “Reading Capital” (1968), articulates that the most important thing of the whole contribution of Marx is that he made his subject of inquiry visible. The old subject of classic political economy was labor and labor power, however only with Marx the subject of inquiry became clear; Laborer (the human – me and you) and not labor it self (not the productive effort of humans but humanity itself). My labor time, or labor force, in a capitalist society is simply my life itself, the human species being. You and me – our life – are the subject of inquiry of Marx.

Here we might re-think the main graphic of the course (published above), is it “labour power” with “means of production” who produce commodities, or instead “labourers force” with means of production- me and you interning relations with things and machines!

For Althusser the answer is clear, it is laborers and not our productive power that matters first. Here, we cannot see the full picture without thinking of fetishism. fetishism of production (and not fetish of consumption) is the driving force of the Madness of Capitalist reason.

I would love to share with you this five minutes from Samsara film (2011) on fetish of producing food:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k56NBsZXjr8

on another side here is a link of the colloquial Arabic translation of Harvey’s second lecture, titled;

Breaking the value barrier … is the capitalist system collapsing?

https://qira2at.com/2018/09/19/harvey-lecture-2/

Thanks for this summary and these guiding questions! Briefly, I’ve been thinking about alienation in relation to these lectures and to comments about organizing. Part of what I get hung up on — and building on what Patrick wrote above — is a tendency to think of alienation as primarily a personal (bad) feeling rather than, as Marx describes it, a relation, wherein both the activity and the products of labor become external — and, to the workers specifically become hostile.

In the spirit of Hegel, Marx understands this process to be a total one, affecting, as we’ve said, capitalists and proletarians alike. But their experience of alienation diverges. Marx writes in “Alienation and Social Classes” (p. 133 in the M-E Reader):

“The possessing class and the proletarian class represent one and the same human self-alienation. But the former feels satisfied and affirmed in this self-alienation, experiences the alienation as a sign of its own power, and possesses in it the appearance of a human existence. The latter, however, feels destroyed in this alienation, seeing in it its own impotence and the reality of an inhuman existence.”

So alienation as a relation becomes universal under capitalism, but not as a universally bad feeling. We can relinquish any guilt, then, about whether we should be attending to the capitalists’ alienation — they love it.

It doesn’t seem to me that posing the different experiences of alienation, that of the proletariat and that of the capitalist, as a question of which to focus on is a useful theoretical basis for anti-capitalist organizing. This is of course not to say that the experiences of alienation are not different—Marx delineated various forms of alienation under capitalism, with workers experiencing alienation in the product, in the process of production, from fellow workers and from capitalists, capitalists alienated from workers. Together, for Marx, both workers and capitalists were alienated from their creative potential to transform the world around them and humanity itself (i.e. “species-being) and taken together, these forms spelled alienation as the total condition of humanity under capitalism. It was not his theory of alienation, then, but his explanation of the wage-relation (which could be described as a theory of exploitation) that allowed Marx to later argue workers would be the emancipatory agent—although both capitalists and workers are alienated, it is the worker that is exploited in the process of the production and the capitalist that does the exploiting and comes out with the value the worker has created.

So, it seems that Marx’s theory of alienation and his theory of exploitation present the foundations for two different methods of anti-capitalist organizing—his theory of alienation presenting a moral argument for anti-capitalist action and his theory of exploitation providing a guiding analysis for intervention into the mechanisms by which the worker is exploited and the capitalist is compelled to continuously make a profit (in the face of the falling rate of profit as Harvey discussed).

With both the worker and the capitalist alienated, I do not see the basis for the argument that anti-capitalist efforts should focus on the alienation of the worker—in fact, it seems vital that there exists an alternative moral framework through which capitalists can filter their experiences of alienation and that competes with the capitalist logic that compels and demands they continuously turn a profit. What is important is that any calls for anti-capitalist action made on such a moral basis be backed by anti-capitalist action itself, action that disrupts the exploitative practices of capitalists in the way that Patrick has described. These practices are grounded in the wage-relation between capitalist and worker, so again, this is not an either-or question.

I tend to agree with the last two commentaries on alienation: 1) distinguishing between alienation among laborers from the fruits of their labor power and among capitalist’s coming to terms with the state of alienation, that is with “living capital,” and as well 2) to what extent we employ alienation as a stand-in for “feeling bad” and personal feelings, perhaps does not get us closer to a fuller understanding of the ways Karl Marx used “alienation” as a term to name a processes required by Capital. Or as Karl Marx put it, “Capital as a special kind of commodity also has a kind of alienation peculiar to it” (p. 184, companion). I think we might want to reconsider how Karl Marx used the term “alienation” as a way to name a function, relationship, and a set of activities associated with Capital. In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1988), Marx describes these processes rather frankly,

from the worker’s standpoint:

“The worker puts his life into the object; but now his life no longer belongs to him but to the object. Hence, the greater this activity, the greater is the worker’s lack of objects. Whatever the product of his labor is, he is not. Therefore the greater this product, the less is he himself. The alienation of the worker in his product means not only that his labor becomes an object, an external existence, but that it exists outside him, independently, as something alien to him, and that it becomes a power on its own confronting him; it means that the life which he has conferred on the object confronts him as something hostile and alien”

“Til now we have been considering the estrangement, the alienation of the worker only in one of its aspects, i.e., the worker’s relationship to the products of his labor. But the estrangement is manifested not only in the result but in the act of production within the producing activity itself. How would the worker come to face the product of his activity as a stranger, were it not that in the very act of production he was estranging himself from himself? The product is after all but the summary of the activity, of production. If then the product of labor is alienation, production itself must be active alienation, the alienation of activity, the activity of alienation. In the estrangement of the object of labor is merely summarized the estrangement, the alienation, in the activity of labor itself”

“He is at home when he is not working, and when he is working he is not at home. His labor is therefore not voluntary, but coerced; it is forced labor. It is therefore not the satisfaction of a need; it is merely a means to satisfy needs external to it.”

and from the non-worker’s (eg. private property owners) standpoint:

“First it has to be noted, that everything which appears in the worker as an activity of alienation, of estrangement, appears in the non-worker as a state of alienation, of estrangement. Secondly, that the worker’s real, practical attitude in production and to the product (as a state of mind) appears in the non-worker confronting him as a theoretical attitude. Thirdly, the non-worker does everything against the worker which the worker does against himself; but he does not do against himself what he does against the worker.”

“This contradiction between landowner and capitalist is extremely bitter, and each side gives the truth about the other. One need only read the attacks of immovable on movable property and vice versa to obtain a clear picture of their respective worthlessness. The landowner … depicts his adversary as a sly, haggling, deceitful, greedy, mercenary, rebellious, heart and soul-less cheapjack–extorting, pimping, servile, smooth, flattering, fleecing, dried-up twister without honor, principles, poetry, substance, or anything else-a person estranged from the community who freely trades it away and who breeds, nourishes and cherishes competition, and with it pauperism, crime, and the dissolution of all social bonds.”

“And partly, this estrangement manifests itself in that it produces refinement of needs and of their means on the one hand, and a bestial barbarization, a complete, unrefined, abstract

simplicity of need, on the other; or rather in that it merely resurrects itself in its opposite.”

Thus, it seems an understanding of the totality of Capital, requires understanding all forms of alienation required by this process, including the ways workers are alienated from what their bodies are capable of producing and, as significantly, of non-workers from the societal realities of wage-labor. A one-sided account of alienation, as Marx further explained in the manuscripts, leads to a figuration of workers as lacking and one-dimensional and non-workers as robust and multi-dimensional. On this type of vulgar manner of political economists, of his time, Marx further explains,

“To him, therefore, every luxury of the worker seems to be reprehensible, and everything that goes beyond the most abstract need-be it in the realm of passive enjoyment, or a manifestation of activity-seems to him a luxury. Political economy, this science of wealth, is therefore simultaneously the science of denial, of want, of thrift, of saving-and it actually reaches the point where it spares man the need of either fresh air or physical exercise. This science of marvelous industry is simultaneously the science of asceticism, and its true ideal is the ascetic but extortionate miser and the ascetic but productive slave. Its moral ideal is the worker who takes part of his wages to the savings-bank, and it has even found ready-made an abject art in which to clothe this its pet idea: they have presented it, bathed in sentimentality, on the stage. Thus political economy-despite its worldly and wanton appearance-is a true moral science, the most moral of all the sciences. Self-denial, the denial of life and of all human needs, is its cardinal doctrine.”

“Ricardo school, however, is hypocritical in not admitting that it is precisely whim and caprice which determine production. It forgets the “refined needs”; it forgets that there would be no production without consumption; it forgets that as a result of competition production can only become more extensive and luxurious. It forgets that it is use that determines a thing’s value, and that fashion determines use. It wishes to see only “useful things” produced, but it forgets that production of too many useful things produces too large a useless population. Both sides forget that extravagance and thrift, luxury and privation, wealth and poverty are equal.”

Which is to say, there is a contradiction that arises when we, scholars, speak about “the worker.” If we figure “the worker” as one-dimensional, then we concede that what should be theoretically given to “the worker” is everything it lacks. This “theoretical” attitude is integral to the non-worker’s estrangement, and as well to the worker’s alienation since theory informs politics and economics. For example, the proliferation of think-tanks within the circuits of economists and political strategists, which have produced countless reports, that have significantly informed economic policies – if not, directly copied – speaks to the integrality of the knowledge economy to Capital formation. I believe this reality has been discussed several times during our lectures, however, what I am attempting to point out here is how Karl Marx continues to push us to think about how concepts both grow from lived experiences and participate-in reforming human activity into particular socially necessary relationships. Thus, an account of how a knowledge economy appropriates the labor of workers that negates the other side of this process might lead to a misconception of the reality of the forms of Capital exploitation we are hoping to understand, and organize against.

Thus, in returning to the discussion about whose alienation we should care about or emphasize, we seem to be missing quite a bit in our analysis if we accept a decidedly one-sided analysis of alientation.

For example, say, we don’t look at the state of alienation that “capitalists” take for granted, then how are we going to understand the maneuverings after the fiscal crisis caused by proliferation of circuits of securitized credit default swaps, aiding the growth in market value for (empty) houses, abetting predatory lending practices, and shifting power of domination from industrial to fiscal capital. Surely, these kinds of generalizations are quite easy, yet maybe necessary to understand the totality (re)produced by the processes necessary for Capital formation. Nevertheless, continuing to discuss capitalists as a general type that exists in the world, apart from sociological and anthropological analysis, is the “poverty of theory”, I think, E.P. Thompson (1978) was aiming to name, in his glossing of Althusser’s most scientific and structuralist writings. As is pointed out in the diagram of Capital’s hydrological-like appearance, produced by David Harvey, Karl Marx found it necessary to distinguish between kinds of capitalist’s (eg. industrialist, financialist, merchant) required by Capital.

Harvey’s diagram is also helpful for visualizing the relationality of anti-value that haunts the law of value in capitalist society. How are we to understand the fiscal crisis of 2008 apart from the ghost of anti-value which swept across the media of fiscal capital, when Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers folded under.

On the question of alienation: perhaps, the financial capitalists of Wall Street were not forced to come to terms with their alienation from the means to a full life – given the strength in the enforcement of money policy – but many financial capitalists were forced to come to terms with a decrease in the quality of living they had associated with their social reproduction. Though, what we have learned is that financial capitalists have no other “fix” except for the continuance of fiscal policies that valorize interest-bearing capital. But this would seem inevitable or natural to “being” capitalist, if not for Marx who provided us a term to understand how non-worker’s come to face a “state of alienation.”

Moreover, and from this perspective, I have begun to wonder to what extent has our notion of alienation slipped into a discussion of immiseration, because it might signify our political valence – that is, our solidarity with those workers who daily face “overwork and premature death” – but then not, necessarily, a sober analysis of forms of alienation specific to our historical conjuncture (and to previous historical moments relevant to this conjuncture). In so doing, an analysis of the process by which a worker sells their labor power, through a wage relationship, is skirted for a discussion of immiseration, qua alienation, of this universal figure: “the worker.” Immiseration is not the same as alienation, although they are necessary bedfellows.

I make this point not to be pedantic, but rather to point our attention to sites from which our concepts are coming from, in our present conditions, and our living embodiment of species being, especially given the importance of the dialectical relationship between the forms of estrangement the worker and non-worker face; in short, our praxis.

———————————————————–

To be polemical, why are we discussing the Russian Revolution? It seems more likely that, at this moment, and since our seminar is being held in the US, specifically New York City which remains “branded” as the capital of the world, we must begin to discuss, and question, the history of how racial logics and capital logics have become co-constitutive. W.E.B. Dubois’ analysis of the reconstruction efforts in the US south after the Civil War waged between the industrialist classes of the North and the oligarchy of plantation landowners of the South, over the question of slave labor or “free” labor, seems to be far more instructive. If not for the simple fact that the superpower whose political structures and social institutions were shaped by how race and class were renegotiated in the antebellum south and throughout the US nation after the world wars. But then race and capital preceded the formation of the US as a globally interested nation-state during the early part of the 20th century. While DuBois was apt to describe the origin of the “psychological wages” as arising during the Jim Crow South, many scholars have demonstrated the deep origins of race in the political economy of colonialism (Robinson 2000, Quijano 2000) and nascent ideologies of ethnos and nation (Bennett 2018; Mignolo 2011) prior to the late 19th century.

Furthermore, we might want to consider how alienation experienced by workers is not simply their confrontation with a world in which they make most of the commodities floating around in markets and storefronts, while they live precarious lives, and only able afford basic amenities, but also an estrangement and subordination to Eurocentrism: either it be the form of exalting the conflation of whiteness and beauty, or European thought as the site of theory, or Europe as the only historically relevant political struggle. Let alone what it means to live with being constructed as actually being an alien thing, broadly speaking. Here, of course, I am discussing what I have noted among workers organizing against accumulation by dispossession. But is that too delimiting an analysis? or praxis?

Thus, the significance of authoritarian figures like the Koch Brothers, Marie Le Pen, Golden Dawn, Donald Trump, Duterte, Bonoraro, and the like, employing populist politics against various formulations of the alien and dangerous other, seems vital to the analysis of our present conditions.

——————————————————–

There was a curious passage I gleaned from a Humans in NY post that I found on Instagram this past month. It reminded me about the estrangement of non-workers from the state of alienation defining capitalist society, but then also to the question of ethics, and of course, morality as mentioned in a previous commentary for this week.

The post includes the picture of a mid-aged white man with a scruffy beard that is turning white. His expression gives off, to me at least, the appearance of a curmudgeon.

He is quoted saying, “When it starts to get crowded, I’ll leave. Because I can’t stand the looks. You know how many people were gonna sit on that bench over there, but decided against it, because of what’s sitting right here? I drank myself into homelessness. So I’m not looking for violins or tissues. But I used to be in the mainstream. I was somebody once, and people used to look at me without any barriers or animosity. I can tell you this: when John Lennon sings ‘Imagine,’ it’s complete bullshit. He was living in the Dakota when he wrote that, overlooking Central Park. Imagine no possessions? He should have written a song about all the wonderful things that he had. Imagine nothing to live or die for? No Yoko? No career? No child? No fame? No status? Well here I am. There’s no peace here.”

What I found provocative is the indictment he makes about the site of John Lennon’s imagination, the direct experiences and iconic images from Lennon’s life, that he left out while “imagining.” There seems to be a warning here, even for those of us grounded in a philosophical praxis of struggle and anti-capitalist thinking and action, which does not correspond with the either Lennon’s easy utopianism or the indicter’s lacking political and economic frames, and it is a warning about what interactions our anti-capitalist thinking is nested in.

Bennett, Herman L. 2019. African kings and black slaves: sovereignty and dispossession in the early modern Atlantic.

Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 1988. Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844 and the Communist Manifesto. Amherst, N.Y.

Mignolo, Walter. 2011. The darker side of Western modernity: global futures, decolonial options. Durham: Duke University Press.

Robinson, Cedric J. 2000. Black marxism: the making of the Black radical tradition. Chapel Hill (N.C.): University of North Carolina Press.

Thompson, E.P. 1978. Poverty of theory. NYU Press.

Quijano, A., 2000. “Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina.”

There are a lot of important threads here that could be quite expansive on their own, but I’d like to speak a bit on the questions and critiques surrounding possible interventions (will post more on theory later or carry onto next week). Especially since I think the Action side of the course will likely mostly be discussed on this blog and I think interim economic interventions should really be considered a form of Action.

I was unfortunately teaching during the first lecture, but I’m told Harvey took particular aim at “autonomist” projects (i.e. squatting) that seek to create alternative spaces, outside of, while remaining within the shell of capitalist systems. Evidently he was quite clear in his view that these are easily recuperated kinds of actions. Harvey’s polemic against this type of autonomist organizing seems tied-in to me with the above critiques of projects like universal basic income in the broadest sense – that is they are all connected to this notion that falling rates of profit lead to a capitalism that is extraordinarily recuperative, imperialist, and ingenious in terms of expansion.

At the level of Anti-Capitalist Action, I think we should recognize that all organizing efforts and initiatives are necessarily piecemeal and serve as propaganda as well as (if not more so than) systemic disruptions. The notion that minimum wages, universal basic income, occupations, etc. can be integrated successfully seems to me to be primarily a condemnation of reformism or the Social Democratic ethos much more so than a dire threat to the anti-capitalist project itself. Everyone, whether they call themselves an anarchist, communist, or Republican, recognizes the purpose of minimum wages and UBI – to reduce inequality and to improve the lives of the poor and working class. If they fail to do as much, or provide only minor relief, it should only make one thing much more clear: world (or international) revolution should still be the primary objective of the socialist movement. Rather than evaluate interventions based on the criteria that they be tangible barriers to capital accumulation I think we should be judging based on very different standards. Did they help build a revolutionary movement? Did they create lasting infrastructures? Did they popularize belief in the viability of alternatives? Did they create convincing political or economic theory for a post-revolutionary society? If your intervention convinces a sizeable number of people that capitalism is monstrous, that radical forms of democracy are viable, that socialism is something desireable and not equivalent to Soviet totalitarianism, then I think you are likely an immensely successful anti-capitalist organizer. That can include supporting reforms to labor laws, occupations, UBI, or what have you depending on the circumstances and balance of forces. The key is to coalesce such interventions into a movement that is capable of actual revolutionary action.

The international left today is recovering from the Marxist-Leninist hangover and I believe much of the extreme disagreement around tactics reveals a level of subconscious defeatism that hasn’t quite died off – the lack of belief in the possibility of a new wave of bonafide revolutions. While it’s an unhappy term today (but relevant to the notion of alienation) I still believe “consciousness raising” and organization building is the primary goal of a resurgent left and many of the often attacked “failures” (Movement of the Squares, Anti-Globe, etc. etc.) of recent memory have been quite successful on those terms.

To unnecessarily widen my anti-Marxist polemic: while I like much about Marx, my personal allegiances are on the Bakuninist side of the First International split. All of these potentially recuperated interventions I think point in part to the dangers of transitionary, class-war/class-repression, and political action (and State) oriented approaches to socialism – both Marxian and Social Democratic – which have failed us all unanimously. In the first they’ve created new class systems that incentivized management along capitalist lines. In the second they adopted forms that easily fit into the legal and diplomatic framework of existing global capitalism. Then they’ve performed such easily integrated interventions on the local level, substituted them for revolutionary action, and found themselves shocked that neither class or state seemed to be withering away. This is different, I think, than the Bakuninist social war ethos that identifies capitalist social relations as its target and refuses the conquest of State and political party in existing structures. Point being I believe we should be considering things to be “actually” socialist economic interventions in this context – not in a national parliamentary legislature – but on the level of democratic, federated, self-managed institutions under “popular” control. But of course self-managed territories or federations that still MUST interact with the capitalist oriented outside world.

So I do believe we have to be extremely attentive to economic theory, just from a post-revolutionary lens, and I don’t believe an anarchist orientation absolves you of the need for such theory. Rojava has a highly anarchistic ideology and it has revealed just how difficult it is to create alternatives, regardless of reliably holding territory in a revolutionary context. Their economic vision is almost Proudhonist (or Parecon-y), creating voluntary cooperatives (a la his worker’s associations) that claim to be trying to produce and sell based on “use value” rather than “exchange value” (much like Proudhon’s “real prices”) which are ideas that have long been attacked. Clearly there is much left to do to eliminate capitalist relations and their situation has been highly contingent on international markets, especially vis a vis oil.

Apart from Parecon and Spanish anarchist’s trade-unionism, there hasn’t been a much of a paradigm breaking effort to update socialist economics under anti-authoritarian conditions since Proudhon and that, to me, is one of the biggest tragedies. One I won’t seek to rectify here in my compulsory diatribe.

Perhaps next time I will hew closer to the discussion and I ask you all to forgive me for the tangential diatribe. But thank you to everyone and everything I used as a strawman to attack or otherwise render 2 dimensional.

I would like to address the second question, namely, examples of movements that reveal alternative forms of value, by picking up on the post-capitalist project in Catalonia that was discussed by Pere. I recently read the following report on the Catalan Integral Cooperative (CIC) by George Dafermos http://commonstransition.org/the-catalan-integral-cooperative-an-organizational-study-of-a-post-capitalist-cooperative/ and found their networks of multi-purpose self-managed associations and projects just as interesting as their use of an alternative currency that was the focus of Pere’s discussion.

What I found interesting is the comprehensive nature of their vision, how the CIC attempts to transform various aspects of its members’ lives in building an alternative system of production, consumption and finance, as well as social reproduction to a degree, and how –guided by alternative values– they transform social relations in each of these spheres. The CIC is an umbrella organization of cooperatives, producer-consumer networks, and various projects, whose long-term goal is to replace the capitalist system and the state. They set up their own productive projects, food supply systems, shops or distributive centers, a basic income scheme for those who coordinate the CIC’s activities, collectives for open design development of technologies, legal and educational services, their own currency and an investment bank. There are 40 or so local exchange networks around Catalonia where products are exchanged either through barter or some variant of the “eco” currency developed by the CIC, which works as mutual credit registered on a local online platform.

Reading Harvey’s Marx, Capital, and the Madness of Economic Reasons, I discovered a framework that could be useful for assessing the potential of movements to transform the existing system, namely the seven moments, seven interrelated aspects or relations that constitute the totality of our lives (just like circulation of capital is approached in its totality through the three spheres of valorisation, realisation and distribution). These are “technologies, the relation to nature, social relations, mode of material production, daily life, mental conceptions and institutional frameworks” (113). Each of these has to be considered when we talk about the change of a system, according to Harvey:

“Most work in social sciences favours some ‘single bullet’ [single moment] theory of social change. Institutionalists favour institutional innovations, economic determinists favour new technologies of production, socialists and anarchists favour class struggle, idealists highlight changing mental conceptions, cultural theorists focus on transformations in daily life, and so on. … The failure of Soviet communism can largely be attributed to the way the interaction between all seven moments was ignored in favour of a single bullet theory of the proper path to communism by way of revolutions in the productive forces” (114).

Therefore, “conscious revolutionary change … entails a redefinition and redirection of existing movements across all moments” (115). That’s why I find the CIC to be an interesting case study as they aspire for a total change of various relations subsumed in and controlled by the capitalist system. So which moments is the CIC attempting to address?

Technologies: they design their own tools and machines, adapted to local needs and small scale of production, that anyone can make and use, thus based on the principle of free sharing of knowledge.

The relation to nature: localized production and consumption of food based on principles of sustainability (permaculture, localism and de-growth); rethinking of needs and thus of the need for mass production of commodities to satisfy artificially created wants and desires.

Social relations and mode of material production: removal of means of exploitation and appropriation by downsizing and democratizing spaces of production and distribution, as well as making means of production more easily available; use of money only as a means of exchange or interest-free investment to facilitate new projects; the goal of the credit system is thus to redirect local resources to local needs.

Daily life and mental conceptions: re-connecting people in local communities through personalized networks of exchange and sharing; collectivist worldview and commitment to serve public good, not only that of the members of networks, but of community in general.

Institutional frameworks: decentralized network of coordinated groups and projects, with democratized control and management on every level and in every field.

Labor, and the surplus that can be extracted out of it, is no longer the value that drives economic and social relations; profit, accumulation and self-enrichment are not the goals of people’s activities, but rather the well-being of a community and satisfaction of everyone’s needs.

While the CIC presents an aspiring model of an organization of social relations based on anti-capitalist values, it is hard for me to imagine how such a post-capitalist “island” can actually challenge the capitalist system that thrives all around it reinvigorating itself through periodic crises. How can an initiative like the CIC bring about a change for the majority of the population –who are not so easily drawn in into these “islands” of self-sufficiency– without putting direct pressure on banks, corporations and the state? And then of course, the question of self-sufficiency: half of the funding for the CIC comes from the so-called “economic disobedience,” that is, getting tax refunds in not-so-legal ways. Can they be completely self-sufficient without resorting to the system for resources, having to deal with rent and other expenses? Can we as easily find affordable spaces, for example, in NYC? (According to the report, the major CIC initiatives were able to get low-price deals in abandoned spaces or spaces that were about to be foreclosed). Furthermore, given the scale of problems that we are currently facing (think climate change), it is unlikely that they can be resolved without resorting to the state and international institutions.

I’d like to expand on some of the points made above regarding alienation under capitalism. As others pointed out, and as is well-known, workers labor under conditions and for wages over which they have little (formal) control, and the wealth they collectively create is appropriated by private owners. Private owners, or capitalists, surely enjoy the benefits of this theft. But, as Patrick pointed out, they must be relatively frugal with their profits. Once the day is over, capitalists may indulge with fancy dinners, fast cars, and fabulous properties. But the majority of profits must be reinvested in a new round of commodity production the following day, or else they cease to be capital (value-in-motion). Production must begin anew. And not only that – capitalists are also forced to make certain decisions about how, where, and to what extent production is to carry on. Because of the coercive laws of competition, as others have described, individual capitalists constantly face competitors who are more productive and/or have lower overhead costs in the form of wages, benefits, taxes, rent, etc. In the face of competition, they too must slash overhead and ratchet up productivity to the greatest possible extent. And increased productivity causes a fall in the unit-cost of a given commodity, so in order to raise the rate of profit in the face of lower consumer prices it becomes necessary to capture ever-greater market share. Given these constraints on individual firms, margins are often slim, the potential costs of disruption great, and the possibility for crisis very real. The coercive laws of competition force the capitalist’s hand in objective ways; they alienate, to a large degree, his/her freedom and individuality in matters of the firm.

The importance of understanding alienation as a phenomenon faced by both workers and capitalists is to underscore both the anarchic nature of capitalism (no one is in charge) and its propensity for creating all manner of harmful (life-shortening) externalities for workers and their environments. As a result of competition, production becomes both more intensive and more extensive. Capitalists reorganize the process of production to increase productivity and devalue labor. The effects of this for workers are well known – immiseration in the form of low wages, harmful conditions, growing levels of un/underemployment, and rising inequality. And through imperialism, capitalism establishes new sites for production, consumption, and the accompanying forms of immiseration.