[lead bloggers: Hilary Wilson, Anthony Ramos, and Benjamin Rubin]

In his first lecture in the series, “Anti-Capitalist Thought and Action,” David Harvey created a foundation for understanding the problems of capitalism today, by thinking through Karl Marx’s Capital. Rather than an ideological commitment to (capital M) Marxism, Harvey is motivated to return to a Marxist conceptualization of political economy out of a concern for capitalism’s inherent tendency toward compound growth, and the social and ecological catastrophe it has created. We have lived through a crisis of capitalism that was resolved through debt financing; and are currently in a phase of ever-increasing debt to finance the required growth. Why debt? Money is the only form of capital––unlike productive capacity and commodities––that can increase without a physical limit, and so for the past ten years, money-creation has been turned to in order to pump up economies that can not grow fast enough by other means.

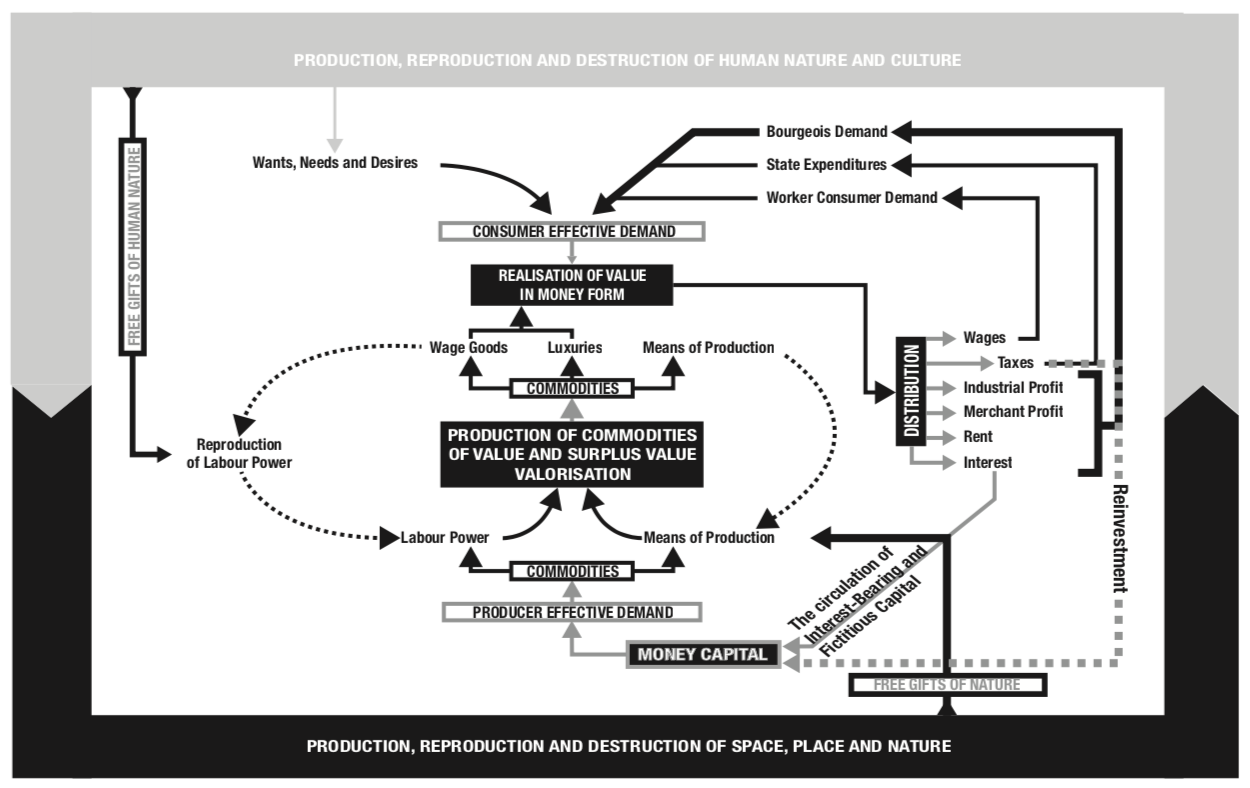

Harvey introduces this lecture series by turning the basic diagram of capital accumulation, M-C-M’, into an expanding cycle or spiral. The diagram has many complexities, but the central point is that capital moves between three distinct phases: 1) Valorization of capital through the production of commodities, 2) Circulation of capital in which it is realized as value, and 3) the Distribution of capital, in which the value in money form is divided between different groups according to different levels of social power. Each of these corresponds to a single volume of Marx’s opus, Das Kapital, and entails particular sets of social relations that operate according to particular logics. While each phase is related to the others, these relationships are not deterministic. Further, because each volume explores only one of these phases, it analyses that phase as if the other two were unproblematic, assuming away the contradictions arising from other the phases. The remainder of this post will give an overview of each phase in capital circulation which was covered in Harvey’s lecture.

Valorization:

Volume I of Capital focuses on the phase of valorization or production. The principal goal in the valorization process is the production of relative surplus value, which can be understood as the equivalent of money capital plus surplus value extracted from labor power. In order for capitalist production to function, there must be an adequate money system and commodity market in place or it must be created. Money capital is used to purchase two kinds of commodities: labor power and the means of production (e.g. physical capital in the form of machinery), while what Marx called “free gifts of nature” (including human nature), are appropriated as the raw materials for the production process. Like subsequent volumes of Capital, Volume I operates under certain assumptions in order to illustrate the particular rules governing the valorization process. Namely, landlords, merchant capitalists, and bankers – all of whom figure prominently in the distribution phase – are largely absent from Volume I. Further, it assumes there are no barriers to the realization of value, which becomes an important point of contradiction in Volume 2. As such, the primary contradiction animating capitalist relations as they relate to valorization is that between labor and capital, with capital incentivized to drive down wages in order to extract as much surplus value as possible, resulting in the increasing immiseration of the working class. Capitalists also undercut labor power through the creation and maintenance of an industrial reserve army of unemployed and alienated workers, as well as through technological change.

Realization:

In Volume 2 of Capital, Marx turns from production to the circulation of capital. Assuming perfect stability in the other forms (stable production––meaning no technological change, and perfect distribution) allows him to engage in the conditions of realization of capital; i.e. the moment when the value that the capitalist assumes and hopes is embodied in commodity C becomes real money as it is sold in the market for M’.

A key contradiction in this process is that different forms of capital circulate at different speeds: capital-as-infrastructure is built with different lifespans, capital-as-production-technology becomes obsolete and replaced at different rates, and so on. This creates a problem of coordinating different time scales which requires some mechanism of deferring the realization of value into the future, or accessing the money form of capital now, based on assumptions of future realization of locked capital: in a word, credit. Conflicts in the speed of circulation are resolved through financial means. Capital stock is valued at a discount rate, money capital is priced via the interest rate, fixed commodities like homes become streams of payment stretched out over years; all showing how credit relations allow the alignment of different temporalities. However, there is no way to hedge against value loss without facilitating speculation- the system of value can not work without fictitious value.

Distribution:

David Harvey described how Karl Marx understood the Distribution of Value in the Form of Money as not a passive stage in the process of Capital but rather a dynamic and active stage. From Harvey’s diagram of this moment of Capitalization, we can visualize the relationship between various participants in the total process of Capital and how surplus-value and Value (or total value) fold back into the larger process. Particularly evident at this moment is not simply the competing interests among the various factions nor the differences between the forms of value, but rather the contradictions (and unity) between, say, the State’s interest in drawing revenues from wages and the power relations driving down wages in field of production.

While reading through Harvey’s recent book, “Madness of Economic Reason,” I made note of how he described another area of the ‘contradictory unity’ of the field of distribution with the fields of realization and valorization:

‘While a lot of wealth is extracted by capital from realisation, even more is sucked out from distribution. The most blatant form of redistribution has to highlight the declining share of labour in the national product in much of the world and the failure of labour in recent times in particular to receive any benefits from rising productivity… The shift from productive to unproductive labour accompanied by excessive bureaucratisation within both the state and corporations has not helped.” (200).

The solution to this contradiction, as we have witnessed in various historical moments since the 1970s, has been financial “innovations” that continue to make new fictitious forms of value — think quantitative easing and the dark CDO markets — and neoliberal economic policies and political pacts. Less talked about, during our first lecture, were the political mechanisms put into place to secure the collection of debts from those who have been enticed or coerced into taking on loans that “innovative” financial mechanisms are backing. This is particularly noticeable for me, especially as I think through Harvey’s assertion that Marx did not consider the working-class to have a say in the field of distribution. Social movements, including Occupy and recently in Michigan, Wisconsin, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela — as well as progressive/reactionary politics like the Bernie campaign and Brexit — have foregrounded fiscal policy and economic inequality in political action.

Discussion Questions

1. As a phase of capital, production is already a terrain of a particular struggle, the struggle between laborers and capitalists. What are the forms of struggle inherent to the other two phases of capital, realization and distribution? How can conflicts over distribution and realization be made part of a class struggle, or an anti-capitalist struggle?

2. Marx described capitalism’s dependence on “free gifts of nature”. Many scholars have pointed to the similarities between the need for cheap nature, and the need for cheap labor. These are not merely analogous. Historically, a key way that labor has been devalued has been by ideological claims about human nature: that native people are closer to a dangerous nature, and thus less civilized; that women are closer to a nurturing nature, and thus naturally suited to domestic care work. How are these ideologies of nature and human nature reflected in Harvey’s expanding spiral of capital?

3. In his talk, Harvey demonstrated that crises often result from contradictions among the various phases in capital circulation, for example, from the inability to realize surplus value because of insufficient demand. At the same time, Harvey emphasized the necessity for anti-capitalist movements to understand that there are different rules governing different games, engendering different social relations at each phase in capital circulation. But I wonder how a focus on the differences between moments or phases in the capitalist economy helps us formulate a strategy for confronting / resolving crises arising from contradictions among these phases. Put another way, while the relations between workers and capitalists is certainly distinct from that between renters and landlords, or creditors and debtors, it seems that what social movements have been less successful at doing is understanding these relations collectively, as interrelated parts of a totality which calls for an expansive, “cross-phase” approach.

4. Strategy: contradictions inherent within phases of capital, vs between the conflicting demands between the different phases of capital.

For Harvey, many of the contradictions of capitalism can be understood as contradictions between the dictates of capital in its different phases. For example, as valorization of capital takes place through the production process, surplus value is extracted from labor; and thus a pressure exists to lower the costs of labor as much as possible. However, the circulation of capital relies on consumer demand, and thus lower wages––while beneficial for the valorization of the capital invested in the production process––become a problem for realizing that value in the market.

Thanks for the great summary and thought-provoking questions!

I’d like to respond to the first discussion question: 1. As a phase of capital, production is already a terrain of a particular struggle, the struggle between laborers and capitalists. What are the forms of struggle inherent to the other two phases of capital, realization and distribution? How can conflicts over distribution and realization be made part of a class struggle, or an anti-capitalist struggle?

Before providing examples of struggles that correspond to the other two phases of capital (realization and distribution) I would like ot think about the word “inherent” as used in the discussion question.

The struggle at the phase of production has indeed been imagined and often lived as a struggle between two clear-cut opposing forces, capital and labor. However, many groups and situations can of course complicate this dichotomy (petite bourgeoisie, workers earning six figures). In other words, the dichotomy is a helpful heuristic, but is not enough to explain people on the ground, and even less across changing social and historical contexts. As we think through examples of struggle in the realization and distribution phases, we should keep in mind the historical contingency of the movements. When and how is it helpful to search for a dichotomous struggle, a principle uniting all struggles inherent to each phases?

In the distribution phase, we can locate a number of diverse groups, each with important and various political repercussions. These include campaigns for product safety, patients’ rights, healthcare reform, freeganism, really-free markets, and consumer cooperatives. Less organized anti-capitalist resistance at the distribution phase include theft and sharing. To what extent they succeed in being anti-capitalist, if indeed it is one of their goals, would have to be evaluated case-by-case. As far as I can tell, these struggles are more recent than struggles at the production phase. They seem to surge with the consumer as citizen model that took hold in post WWII USA. If indeed we are seeking a common term uniting these struggles perhaps we could locate the struggle between consumer and vender as central.

At the distribution phase, I would locate, among others, movements for debt forgiveness. These moments are ancient and varied. From third-world debt jubilee to campaigns against student or medical debt, we could potentially locate the central struggle as between indebted and the lender. However, that does not seem to cover the wide range of activities in the distribution phase.

These are great discussion questions. In particular I’ve been thinking about the issues you raise in question 2 in regard to the history of race in the US. I think there’s two possible ways of integrating a racial analysis into Harvey’s spiral.

The first is to historically locate social conditions in the free gifts of human nature. The gendered division of labor precedes capitalism, for instance, and the precedents of what would become modern scientific racism predate or happen alongside the development of industrial capitalism. From there, these ideological precedents might just be in a spiral of social reproduction as products of cultural context. I think this is an incomplete picture however.

The second is one that Prof. Harvey alluded to himself. He very briefly pointed to the civil rights movement, women’s liberation, and various New Social Movements as a reaction to the increased inequality of wage distribution among other things. This was in itself a result of the contradiction between the pressure to keep wages low and the need to raise them in order to maintain social reproduction. I think an approach like this that locates gender or race inequality in the processes of capitalism itself has the benefit of analyzing them as primarily material processes instead of ideological residue.

As I understand it, Stuart Hall’s notion of articulation–which admittedly I know only through a reading of Brent Hayes Edwards “The Uses of Diaspora” (2001, pp. 59-60)–is a useful way of seeing how different disparities work into the circulation of value. This is the “unity formed by the combination or articulation” between two separate modes of production that are “structured in dominance.”

For instance, the production and circulation of pseudoscientific racism and the ideological presuppositions it produces and relies on can be viewed as a separate mode of production and value circulation whose primary goal may not be the realization of commodity or money value but that nonetheless contribute to that overall process. Racism is often theorized as the ideological rationale for the creation of a privileged poor white buffer class between the bourgeoisie and working class black people, but I think it can be extended into the realms of value realization (in discriminatory housing market practices maybe?) and distribution (as Harvey briefly did).

I thought it might be a practical idea to compile lists of the readings mentioned by the lecturers, for those who like to geek out on economic and political thinking in conjunction with their anti-capitalism.

References Mentioned:

Collins, Peter. Trust Issues: “Compound interest can help save for the future, or it can bankrupt the world.” Lapham’s Quarterly, IV (4): 2011.

*contains a discussion of Peter Thellusson’s will.

Dickens, Charles, and Nicola Bradbury. 2003. Bleak House. London: Penguin Books.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. Science of Logic. Routledge, 2014.

*on Infinity (§ 316 – § 444) https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/hl/hlbeing.htm#HL1_185

Ricardo, David. Buillonist Debate

http://www.hetwebsite.net/het/schools/bullion.htm

Smith, Adam. “Digression concerning Banks of Deposit, particularly concerning that of Amsterdam.” An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations, 1776.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/smith-adam/works/wealth-of-nations/book04/ch03.htm

Swanson, Ana. “How China used more cement in 3 years than the U.S. did in the entire 20th Century.” The Washington Post, March 24, 2015.

Zhang, Li. Strangers in the city: Reconfigurations of space, power, and social networks within China’s floating population. Stanford University Press, 2001.

I believe that question three raises an important point, namely the importance of considering the three “distinct games” in their totality, as well as discretely. Could a successful counter-hegemonic strategy address a ground-level specific “game” initially to “change the conversation” and thereby influence the distinct social natures of the auxiliary “games”?

I’ve been working with an organization for the last several months which is trying addressing this issue. Currently in the strategic planning phase, we are designing an advanced manufacturing facility in the Bronx that will serve as incubator and workspace for democratically-owned businesses and provide support for women of color. Rather than creating spaces that respond to macro-economic consumer demand (like “internet of things” products geared toward higher-income consumers), the curriculum and resources aim to promote the innovation and production of products and/or services that address endogenous, locally-specific needs. For example, Bronx county has the highest rate of asthma of any urban county in the United States–what technologies could be developed to ameliorate this disparity for and by the people who live there? In granting total and shared access to the means of production (from ideation to final product), could this project subvert classical notions of distribution and realization? Any monetary profit gained from this innovation would be distributed endogenously (because of the cooperatively funded and owned production) and positive externalities (i.e. improved health outcomes) would be distributed as well. I suppose this would fall under the umbrella of “double bottom line” practices, wherein social impact (externalities) are given the same value as monetary returns on investment.

If the “free gifts of nature”, like ingenuity and innovation, were reimagined to serve equitable, non-monetary gains (rather than profit-motivated strategies), could that influence the subsequent circulations of capital?

In response to question 1, and calling our attention to the name of this course- which underscores the connection between thought and action- I would like to think through those anti-capitalist struggles and distinct logics of collective action that we could concretely identify today in each phase of capital:

1. Production. As mentioned by others, the main struggle here is the one between capital and labor. However, as highlighted by Austin, how to understand this relationship today? Given that globalization has imposed new demands and requirements to labor, what are the concrete demands of workers in the multiple contexts whereby capital circulates? Indeed, new labor forms and working force patterns have resulted from the emergence of a post-industrial economy that has transited from manufacturing to services in the last decades. Furthermore, complex labor formations have also resulted from a global transition to greater labor flexibility. This has led to the abandonment of formal labor relations prompting precarious forms of work. As Burawoy notes (2010), wage labor today is a privilege of few rather than a curse, nonetheless, it is also important to note that many workers’ demands are not even centered in formalization per se. Seen all this, is the labor-capitalist division still valid for accounting for the social-labor formations taking place in contemporary global capitalism? Would new analytic categories or terms such as the precariat (Guy Standing), informal labor or casual labor enable us to better theorizing these new labor experiences?

2. Realization. The struggle here takes place when value is transformed from commodity to its money form, that is, at the moment of consumption. As David Harvey notes there are two forms of consumption involved in realization: productive consumption (of those partially finished commodities that capitalist need for production) and final consumption (of wage goods and luxury goods) (12: 2018). On this basis, Marx builds his theory of effective demand according to which capitalists’ insufficient investment or consumption demand may result in their inability to sell their commodities (a failure in realization). In this context, what anti-capitalist practices are occurring in the realm of consumption demand in the present? How to understand an anti-capitalist approach to consumption?

While many anti-capitalist organizational forms of exchange and consumption such as cooperatives and the diverse array of initiatives within the “sharing economy” have advanced anti-consumerist actions as an answer, it is also clear that growth has facilitated a progressive downward dissemination of consumer goods which has increased the access to consumption of affordable goods for a larger groups of people. Is it possible to consider a socialist and ethical defense of a consumer culture while at the same time acknowledging the dispossession and alienation that goes hand in hand with unlimited growth?

3. Distribution. Anti-capitalist actions here take place within the state, the different factions of capital and waged labor. As noted above, however, having a clear idea of waged labor seems to be at least problematic in the face of the contemporary relation between capital and workers. How can a struggle around wages be devised for people working in the so-called “informal economy”? What are the organizational barriers faced by independent free-lance workers who do not rely on any formal employment relationship?

In addition, as Harvey also notes, Marx did not provide a detailed analysis on the appropriation of value and surplus value by the state (2018: 15). What anti-capitalist initiatives have been advanced by states with the objective of affecting the circulation of capital? A concrete action that comes to my mind is ex- President of Ecuador, Rafael Correa’s proposal of introducing an inheritance tax (for large transfers of wealth between family members) as well as an additional tax on capital gains. Although the Ecuadorian Congress didn’t pass this law and we cannot but only imagine the effects of its implementation, Correa’s initiative raises several questions about the role of a socialist project driven by the state such as the one aimed by several south American countries in the last decade. Was socialism of the 21st century in countries like Bolivia, Ecuador or Venezuela a truly anti-capitalist political project?

Thank you very much for the great summary, the difficult but interesting questions and the contributions in terms of reflection and bibliography.

In regard to the first question, I believe that the class struggle inherent in production is not so evident in realization. That is, there is a contradiction between production and realization because it takes place in different places, the first in the work process and the second in the market. In production, the capitalist has the incentive to pay workers as little as possible, to make workers work as much as possible hours at the greatest possible intensity to generate the maximum surplus value at the lowest possible cost, that is, to generate the greatest benefit to the capitalist in the production of value. The production of greater wealth in one pole of society, that of the capitalists, generates the impoverishment of the other pole, that of the workers. In this case, the difference between the interests between the capitalist class and the working class is evident.

However, the workers are important for the realization because in the market they are buyers of commodities. After the Second World War many capitalist countries improved the conditions for the realization of value, giving greater purchasing power to workers (Keynesian policies). From that perspective, one might think that the workers advanced positions in the class struggle because they achieved a material well-being impossible to conceive before the World Wars, and also unrecognizable after the 70s with the neoliberal counterrevolution. However, I also think that it should be taken into account that at that time, in order to overcome the contradiction between production and realization, the use of credit was used, new buyers were found who are not production workers (teachers, doctors, etc.) and Capitalism found new markets in which to sell the commodities.

If we would want to see the class struggle in the realization in exclusively economic terms, then the struggle would be between the capitalist who wants to sell the goods at the highest possible price and the consumer-worker who would want to buy in the market at the lowest possible price. The worker has sold his labor power and has obtained a salary, and his interest would be to maximize his purchasing power by decreasing the benefit that the capitalist obtains from the generation of surplus value. However, I believe that reducing the struggle in terms of offer and demand greatly simplifies the problem in the realization. Improving the conditions for realization ends up perpetuating a system in which workers are in a position of disadvantage despite the fact that it can be argued that the improvement in their salaries between 1945 and 1970 led to increase the capacity for worker mobilization and organization. Improving the conditions for realization increases the capitalist market and enhances the transformation of workers into consumers, which means, their alienation. In addition, improving the conditions for realization through increased consumption also leads to environmental collapse which affects the quality of life of the workers if not their survival capacity. I think that the real struggle in realization would be to get commodities sold at their value without surplus. If that happened, the capitalist enterprise would not make sense. Walter Benjamin said that revolution is the emergency brake of the uncontrolled train of capitalism because it is a system that is not capable of stopping, or even slowing down, its march.

If we look at the distribution of value, the state of class struggle establishes the quantity or percentage of money form after realization that goes to wage labor, taxes, industrial profit, merchant profit, interest, etc. The struggle between wage labor, industrial profit and merchant profit is very clear. However, I think the question of taxes is not so clear, at least for me. Obviously through taxes can be guaranteed a better state for the working class through an improvement in their access to education, health and other services of the Welfare State. However, it also gives greater power to the State and its coercive capacity. Supposedly the State can impose the victory of the working class in the class struggle but in the other hand the State is intimately linked to the capitalist development. Again, as in the realization, I believe that the discussion here is between rupturist or reformist positions.

Finally, I would also like to introduce a question I thought after class. If labor is needed for the creation of value, how can we consider the value crated of a land that has not been worked on and that is being sold?

I want to respond to an interesting point raised by Pere and by Miryam, and perhaps relate it to some of the questions I had from the lecture. The former is the idea that one struggle in the sphere of realization would be to reduce or eliminate the realization of surplus value such that commodities are sold at their value (i.e. not value plus surplus value). As Pere points out, in this case the values that underpin capitalist production, namely the accumulation of surplus value, would no longer make sense. In my own studies of a small cooperative institution that attempts to subvert traditional capitalist realization of value, this is precisely the goal. Commodities that have been produced–albeit according to the capitalist mode of production–are still exchanged for the money commodity, but at a price that effectively does not, explicitly and by choice, realize the surplus value typically added by the seller/merchant. In other words, the markup added by a typical merchant is reduced to the point that it only covers, more or less, the actual costs of maintaining the existence of the merchant, rather than providing for the additional profit that allows the accumulation of capital by the merchant. I’m not sure whether it’s accurate to say that this strategy takes some capital out of circulation, but it definitely does introduce what we could perhaps call a different relation between buyer and seller.

I suppose one of the questions this raises that relates directly to the theme here is: does this constitue anticapitalist action? That is, can the attempt to subvert one of the perhaps fundamental relations within the capitalist mode of production, even though that subversion occurs within and is even enabled by that mode of production and inevitably participates to some degree in a corresponding exploitation, dispossession, and alienation, nevertheless be considered to be anticapitalist? These questions relate, I think, to an idea Harvey points out, which is that Marx’s “capitalist” is a sort of ideal type, or perhaps more precisely that being a “capitalist” is not a matter of the qualities one possesses or the particular notions one has about the world, but one what does. In other words, being a capitalist is using money in a particular way, such that anyone who, for example, owns stocks or has a pension or retirement account that invests money today in order to (hopefully) have more money tomorrow is, in and by that action, a “capitalist”. Most if not all of us are in this sense capitalists. Similarly, everyone who participates in the market is also alternatingly both buyer and seller at some point, as well as one or the other of these simultaneous to being a capitalist. But this is not to say that the buyer/seller relation is analogous to the capitalist/worker relation, simply occurring in a different sphere of the totality of capitalism. Rather, it points to one of the notions that I think Marx is trying to get at, which is that we are all more or less complicit with the exploitation, dispossession, alienation, and crises that are produced by the mode of production in which we inevitably even if not by choice participate. I’m not sure exactly where this gets us, but I definitely don’t think it only gets us to the resignation to complicity. If anything, I suppose it’s a potential point of intervention.

Thank you all. It’s excited to get started.

I would like to consider the notion of “anticapitalism” broadly through a performative lens, in a manner that relates to the premises underlying Questions 1 and 3. It strikes me that there are two ways we could consider the notion of “anticapitalist action”: 1) as radical/revolutionary, or 2) as reformist/progressive. Granted, this is a reductive move which begs further expansion, but I think that this contrast reveals some of the promises and perils that anticapitalists face today.

It’s clear to me how historical versions of Communism (e.g. Soviet, Cuban) and Socialism (e.g. Nazi/Italian Fascism) offer alternatives to the market-driven incentives that belie the capitalist order. But things get somewhat murkier when considering examples of contemporary movements today (especially in the US) – very few of which propose a radical new system of production to wholly replace capitalist production. This generally seems true for Occupy, which for instance was clearer about its critiques and about manifesting an alternative order through public performance than it was about articulating an economic model that would replace capitalism the capitalist mode of production (though I am sure those conversations were raging). They did intervene significantly in terms of the distribution of debt in their Rolling Jubilee campaign, which used donations to buy and forgive the debt of homeowners at a mere fraction of what it would take them to pay it off.

Still, I wonder if Occupy, was (by default) something of a reformist/progressive organization that used radical performance and participatory structures to manifest micro-alternatives. In so doing, they successfully articulated broad commonalities between the occupiers to a national audience, while drawing a distinct contrast to the order that dominates the corporate offices in their background.

It can be scary to talk of a total revolution to replace capitalism, especially in the eyes of everyday US-Americans. I am thinking particularly of the Weather Underground, the 1970s revolutionary political group that dissolved the biggest student movement in the history of the US (which was channeling millions of people in protest of the Vietnam war). At the height of their power (summer 1969), a handful of their most charismatic leaders took over the organization and reoriented it towards the violent overthrow of the US, in hopes of replacing it was Maoist Communism. They failed, and triggered a massive political backlash that made “activism” seem scary. That said, it is certainly conceivable that others could do it better, but therein lies a danger.

Alternatively, in the reformist/progressive mode of thought, we might productively consider the role of social movements as corrective forces that act upon capitalist organization. Indeed, we might anticipate and account for their eventual absorption into the capitalist framework, embracing the notion that all movements must die. But these strategies might not fall squarely within the bounds of “anticapitalist action,” depending on how rigidly we draw that definition.

I will end with a question: Is it possible for other forms of organization to exist alongside capitalism (e.g. Social Democracy in contemporary Scandinavia)? Marx tries to account for the effect of taxes within his model, which we might consider to be an anticapitalist force, or at least one with the potential to benefit the working class. Given that information, is any system that uses capital therefore inherently “capitalist”? And if it can coexist with other forms of organization (which I believe it already does), how can we speak productively about this in terms of Marx’s model?

Thanks for your clear outline and thought-provoking questions—and for going first.

I’d like to follow on the third question regarding how analysis relates to strategizing across the different “moments” of a broader capitalist system.

Harvey was abundantly clear in pointing out the fact, often missed by some drive-by citation styles, that Marx in Capital is consistently writing under, revising, relaxing, and reintroducing a shifting set of assumptions in order to illustrate certain immanent tendencies (occasionally acting at cross-purposes) within the laws of motion of capital. This level of abstraction is extremely helpful as a form of complexity reduction, insofar as it allows us to discern some meaningful shapes from within the quicksands of creative and not-so-creative destruction that set the terms, intensity, and distribution of so much of our world’s suffering—even if it does not depict a world that has actually existed.

But this is because it is precisely that: an abstraction. A concrete person who works in a textile factory may now have an interest-bearing savings account and a measly stake in a pension plan. Few capitalists take the form of a Donald Trump or a Henry Ford, and the commonalities between a shareholder, a full owner, a private equity firm, and a CEO with stock options are all (as was also the case in Marx’s day) more complicated than “the” capitalist Marx portrays. But this does not mean Marx got it “wrong,” or that we can’t use work at this level of abstraction for strategic action. The worker and the capitalist are personifications of a specific—and inherently conflict-prone—social relation, and we can use that simplification to analyze concrete social situations that seem much more messy, like when your boss is a hedge fund or you pay your rent to a ten-digit number.

Part of the strategic thinking behind linking struggles over so-called “primary” exploitation (by capitalist employers) and “secondary” exploitation (by price-gouging merchants, landlords, and creditors, not to mention husbands) is that the really existing people who “make their livings making, moving, growing, and caring for things and people” (as Ruth Wilson Gilmore puts it) experience them all, even if they are a worker in one relation, a consumer in another, and a tenant in a third. A great deal of organizing by the Communist-influenced CIO in the 1930s was specifically aimed at building power among working people (and the unemployed) on these multiple fronts, using the workplace as a central but not sole lever of power. Labor organizer Jane McAlevey has recently re-christened this approach “Whole Worker Organizing” in her book No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age. By moving between these levels of abstraction—as Marx does in his historical account of the working day and the Corn Laws in Volume I—and a concrete assessment of the actually existing situation, Left strategies can do the messy work of bridging the gaps between these different games. A virtuous circle of consciousness formation can emerge through the process of seeing what a landlord’s imperative to pay back a variable interest-rate mortgage has to do with your rising rent, your shrinking wages, and your ruined hometown.

Struggles over the social reproduction of proletarian communities, which Harvey notes Marx likewise abstracted from, can come to be linked in this way to conditions in the workplace, which Harvey emphasized are always in intimate interrelation, mediated unevenly by the state. Just think of how public employees in education in Chicago, West Virginia, and Arizona were able to leverage the power of shutting down their workplaces (sites of paid reproductive labor not organized for profit) to squeeze out gains for the working class more broadly—not to mention the shifts in consciousness that have emerged as a result which provide fertile grounds for strategizing and organizing at other moments.

Thank you for detailed summary and the challenging questions. Since many of posted questions have been addressed I’d like to make a comment about Harvey’s discussion of growth as a key strategic factor within capitalism.

The heightened focus on rapid growth and compound growth is due to its positive correlation with surplus value. Monetarily, growth has no real limit, but the threshold on resources (commodities and production) will be reached eventually through consumption. In our consumerist society, we seem to be rapidly approaching that threshold of resource extraction without paying much attention to the length of time we have left. Growth is generally viewed as a positive, but at what point does growth become negative? Stress from resource extraction due to expansion is currently a pressing global economic issue that does not seem to be taken seriously by capitalist economies. While thinking through this process concerning our global economy a few questions arose concerning the viability of growth as well as incentives for sustainability and a zero growth economy.

-If rates of growth are capped, would a resource limit still be reached?

-There is merit to the argument of growth vs. sustainability, but can we have both in a capitalist economy?

-Is a zero growth economy socially sustainable?

-As we approach a resource limit, is long-term growth an economically viable factor to focus on?

-Is a zero growth economy attainable once we’ve reached the resource limit?

-Are the theoretical benefits of sustainability and a zero growth economy structurally attainable?

I would like to comment on Harvey’s discussion of anti-capitalist movements. More specifically, one of my research interests being the viability of practices and spaces that operate outside capitalist and statist logic, I appreciated Harvey’s brief mentioning of such initiatives and their capability –or lack thereof– to withstand co-optation back into the system.

As he mentioned, in the recent years we have seen a rise of movements –often anarchist-inspired–that claim to operate through bottom-up decision-making practices and that attempt to create autonomous, heterotopic spaces of non-domination by the capitalist system and the state. Take as an example the horizontalism movement in Argentina (Marina Sitrin, Everyday Revolutions: Horizontalism and Autonomy in Argentina, 2012). This movement –and others like it– attempted (we can argue how successfully) to affect different spheres of social life of its participants, going beyond the sphere of production into distribution, consumption, social reproduction and local governance, with a holistic view on the creation of alternatives. It is hard to argue against Harvey’s statement that these initiatives do not withstand the test of time. Besides examples of co-optation, we have seen solidarity economies, mutual aid, food distribution networks, local assemblies emerge in the midst of crisis and then fade away, either because the urgency to create alternatives is no longer there (I assume this may be the case in Greece) or because the state moves in to brutally vacate newly created spaces of resistance (think of Occupy Wall Street or Gezi Uprising).

Yet, despite the short-lived character of these experiments or their eventual absorption back into the system, I see them as important practices enabling us to critically think of effective alternatives. While not intending a tangible win from the system (like a struggle for relief of student debt), they aim to change the fundamentals of social life: the ways of relating to each other that underlie relations of production and social reproduction, where alienation runs deep. They defy – however successfully– the capital’s hold on the state by re-inventing democratic practices whether it comes to economy or social reproduction; they defy the capital’s hold on people’s consciousness by rethinking values, fostering responsibility to the community, and creating more inclusionary spaces. I think we have to take seriously those movement that try to create new subjectivities and a new public sphere: Could these experiments leave long-lasting imprint on their participants? Under which conditions can they resist co-optation or ensure enduring commitment on the part of their participants?

As Harvey argues in his 2015 essay “Listen, Anarchist”, the main limitation of these movements is their refusal to utilize the state as a means or a terrain of struggle. But what happens if initiatives of this type either engage the state on local level (what has been attempted in Turkey’s Kurdistan; see Tatort, Democratic Autonomy in North Kurdistan, 2013) or are actually promoted from above, by the state itself (as in the case of Venezuela; see Matt Wilde, “Utopian disjunctures: Popular democracy and the communal state in urban Venezuela,” 2017)? In Turkey’s Kurdistan, grassroots initiatives –local assemblies, cooperatives, academies, women’s centers, etc.– were set-up and coordinated for more than a decade by the Kurdish national movement. While promoting a project of radical-democratic governance outside the state, the movement, at the same time, participates in electoral politics in order to leverage municipal institutions in promoting its goals. This leads me to my second question: can anti-capitalist movements pursue both strategies — of building enduring counter-hegemonic structures, spaces and subjectivities while actively interacting with the very system that they ultimately want to destroy?

Given the recent victories of progressive candidates in the USA, I would be very interested to look at the interaction of anti-capitalist movements and people that they help to elect on a local level, e.g. Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi and Chokwe Antar Lumumba, called the most radical mayor in the USA, who was elected in 2017. As Kali Akuno, director of Cooperation Jackson, explained in a recent interview at Real News Network, “the overall goal is to build a dual power. So that the community itself can check the repressive apparatus of the state, but also institute its own programs for how to manage its own affairs, how to govern its own affairs at the level of the community absent of the state.”

I think I would like to contribute to this discussion by sharing some thoughts around the limits that intellectual production presents to help solve some of these issues. I believe that these thoughts could also speak, albeit minimally, to some of the points raised in questions 1, 3 and 4—i.e. identifying struggles and contradictions inherent to capital within and outside of the fields of abstractions drawn by Marx (production, valorization and distribution), and how considering the interactions of such struggles and contradictions within a totality might help us strategize transformative politics.

The present conjuncture ostentatiously displays a sophisticated capitalist system that has historically proven itself capable of continuously reinventing itself in innovative ways in order to overcome the contradictions that are inherent to it. We know, however, that the continuity of this trend is unsustainable; that these metamorphoses, or loopholes, or whatever they may look like at different instances, cannot carry on ad infinitum. Thus the urgency of un-bracketing production, valorization and distribution to interact on a single layer, to potentially reveal that which while separated remains outside our field of vision. The impossibility arises upon the realization that bracketing is surely what allowed us to grasp these processes in the first place.

Marx’s assumptions and abstractions are needed to lay the foundation for understanding what we have been referring to as the different phases of capital. These abstractions allow us to map and schematize these processes as seemingly orderly, and appreciate from a certain distance how they manifest and stand autonomously but remain interrelated. As such, to abstract and make assumptions seems a fundamental step for the sake of analysis.

Then, the attempt of incorporating these different phases into a single sphere and observing how the particular contradictions embedded in each phase continue to manifest, transform and multiply through their interactions within an ever-expanding totality becomes a daunting task, if not right out impossible. Portraying a totality that is faithful to the depths of complexities attached to this system could very well represent an intellectual cul-de-sac. I could not imagine such messiness fitting into a schema, much less listed with bullet points. To resist the temptation of ordering/systematizing the mess and let ourselves be overwhelmed by it seems bogus and counterintuitive to academic production, a methodological impossibility. But a pressing one at that.

Contradictions, as such, are not limited to capital but can also be identified in the process of knowledge production itself. If not un-bracketing all together, we need to think about how to build bridges and lines of communication between these different phases and the struggles and contradictions they contain; how to creatively mix and match struggles and contradictions within and outside these phases to suggest strategies and much needed answers.

Hello and thank you for the great summary and discussion questions. In regards to the second discussion question, we see the extraction of surplus value justified through claims on human nature in post-industrial Flint, where laborers have been racially devalued to a point of “permanent surplus” (Laura Pulido 2016 Flint, Environmental Racism, and Racial Capitalism). Much of the black population of Flint has been deemed incapable of value production. This abandonment of capital amounted to a fiscal crisis within Michigan’s neoliberal government, again devaluing the lives of the residents of Flint by knowingly contaminating the population’s water supply with lead in an effort to remain solvent. This embodies both a racial skew in the conflict between labor and capital during the process of valorisation as well as a conflict between all three terrains which Dr. Harvey laid out in lecture and in Marx, Capital, and The Madness of Economic Reason. Flint is baring the brunt of a spatial fix for capital and as such is laboring to create amenable conditions for capital accumulation elsewhere. In Flint, however, inadequate value production and austerity politics starved the state of tax revenues (distribution terrain) resulting in the poisoning of Flint residents and an inadequate social safety net, decreasing consumer effective demand and the realization of value in money form.

One thing that Dr. Harvey mentioned which caught my attention was the fact that the temporality of capital mandates a credit financing system, with interest rates homogenizing time. If this is to be considered a somewhat beneficial aspect of debt financing we can certainly name a litany of hazardous effects in our current state of the compound growth of capital. Dr. Harvey mentioned speculation as a major factor in the 07-08 crash, and that capital requirements on speculation placed on banks after the housing market crash would prove insufficient to stem another crash like 2007. This seems like a moment in which representative state power is necessary to organize human life on such a large scale. Would the nationalization of Wall Street into a public utility, done in conjunction with other countries’ nationalization efforts, help to prevent economic crises moving forward? What would the structure of an American nationalized public financing utility look like? How would the nationalization of Wall Street move us closer to socialism? Should we be organizing proactively on these principles in preparation of another crash?

Thanks for the insightful discussion and series of questions, and comments by all. Although I have many thoughts on these themes in relation to social movements, I will limit and focus my response to problems surrounding question 2, where Marx observes the dependence of the capitalist system upon ¨free gifts of nature.¨ In full appreciation of the complex gendered-racialized nuances with which this question has been presented by our bloggers, I will examine this question in relation to indigenous knowledges and later to the context of ¨cognitive capitalism.¨

While originally, this term F.G.o N. may have been intended to discuss wealth extracted from plants, animals, minerals, and other natural resources, it must be examined in relationship with human labor in the context of colonization, and the grim reality of deterritorialization, mass dispossession of land resulting from capitalist labor practices. To give a sense of scale of this phenomenon, I cite statistics from a statement of Federico Pacheco from the ¨Via Campesina¨ movement: [that] 200 million hectares of indigenous land, water and seeds have been grabbed in the world today. Specifically, back to the discussion of problems related with question 2, I am specifically interested in issues where this relates to the appropriation of indigenous knowledges, which are then redistributed as ¨commodities¨ in the global market. Concerning this, I would like to bring to our attention an article (in Spanish):

http://www.jornada.com.mx/ultimas/2018/09/07/en-chiapas-tejedoras-denuncian-privatizacion-de-tradiciones-9887.html

Summarizing debates from the first Latin American meeting, convened by the Network of Cooperatives of the South (Recosur) for the ¨defensa del patrimonio cultural, saberes ancestrales, propiedad intelectual colectiva y territorios de los pueblos indígenas¨ (defense of cultural heritage, ancestral knowledge, collective intellectual property and territories of indigenous peoples.) In San Cristóbal, indigenous weavers from Chiapas denounced that there has been the ¨dispossession and appropriation of our designs as knowledge of our ancestors, ¨ and “with the advance of capitalism, stores that have appropriated our designs have increased,” while eroding labor rights, as indigenous workers are seen as piece workers, which brings a chain of exploitation ranging from dispossession, and conflict in communities and cooperatives. At a follow up press conference there were also representatives from indigenous groups in Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, Ecuador, Paraguay, Colombia and Mexico.

In general, I would like to examine within the course many questions raised in our blog discussion, in relation to how we can think about Marx´s and Harvey´s model in relation to what has been called ¨cognitive capitalism, ¨ in particular ¨knowledge production,¨ as commodity. This context again directly relates to question 2, in how monetary value to is often NOT ascribed to knowledge production from formerly colonized populations. To contrast the first article, I include a review of the new book ‘Nueva Ilustración Radical’ by activist and philosopher Marina Garces, (the Alt-Globalization movement in Europe, and more recently 15M/ indignados in Spain).

(My apologies again that this article is in Spanish) https://www.elconfidencial.com/cultura/2018-02-18/marina-garces-nueva-ilustracion-radical-entrevista_1522795/?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=BotoneraWeb

She discusses forms of hierarchies of knowledge production as a commodity under cognitive capitalism, and its consumption. Additionally, in relation to the capitalist system we have to examine the production of waste, (again related to processes of dispossession as an effect of the capitalist system) ¨ “A humanity-waste is being produced: people without work, without resources, without water, without habitable land, without a home in the cities, without papers in many parts of the world … It is already a reality that displaces the limits of what we understand by the ¨human¨ and by ¨dignity.¨

In relation to class struggle, we must also examine contemporary conditions of rise of prison labor and precarious workers and working conditions (unpaid labor, no contract work and freelance work), and the importance of various social movements who have unified a formerly classless group of precarious workers, unpaid, or paid often in green receipts in lieu of actual money. [recent national prison strike an important example]. An important aspect of this organizing involves how we are socialized through labor and work; lacking the traditional site of struggle and community of ¨the worker¨ or the working class, prison and precarious workers are effectively desocialized, inhabiting invisible regimes of space and time (quasi-permanent overtime, erratic hours, quasi-permanently on call) that were formerly occupied by the working class. These social movements socialize the despair of the loss of the common site of struggle as the shared work space, and with it the socialization of belonging to a class affiliation, and organization.

I’m mainly interested in question 2 on “free gifts of nature”. I thought it was really interesting that the lead bloggers mentioned the racialization and gendering of ‘cheap’ labor and how that has evolved from primitive accumulation to more complicated forms today. Nature, as a concept, is also interesting to consider in this context when we begin to consider it as an agent in changing capitalism.

In Seeing Like a State, James C. Scott’s analysis of a “scientifically-managed” forest in Germany that was supposed to bolster forest growth miraculously resulted in the opposite scenario. Here, thinking about the trees as agential actors in capitalism starts to break down the rationality of economic thought. What happens when these “free gifts” start acting in ways that rationality cannot make sense of, or fully predict?

Another version of this can be found in Anna Tsing’s ethnography on the matsutake mushroom. The matsutake mushroom resists traditional mushroom farming methods, and its proliferation in a post-industrial forestry landscape complicates our assumptions of nature as either ‘raw’ or ‘untouched’ or scientifically developed and organized (as shown in Scott’s descriptions of the scientifically managed forests.) Tsing’s ethnography helps us see how nature, far from being static, has morphed around our ideas of capitalist destruction.

I’d like to add to the discussion an example of anticapitalist praxis that I recently came across, which I think can be analyzed under the framework Prof. Harvey has distilled from Marx, while demonstrating the difficulty of going from struggle within capitalism to rupture with the logic of the value form.

I recently had the opportunity to visit the Karl Marx Hof in Vienna, which as you may guess from the name, was part of an anticapitalist project in that city. The Karl Marx Hof (Hof=Court) is one of over 300 city-owned social housing complexes built in the “Red Vienna” period of 1919-1934, when the city was governed by the Social Democratic Workers Party (SDAP, not to be confused with the fascist NSDAP).

The SDAP claimed an ideology called Austromarxism, and can be characterized by its pragmatic attempts to build socialism within the political constraints of running a city government in interwar Austria.

Following WWI, workers in the defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire formed direct-democratic “councils” that contested capital for control of the means of production. In nearby Bavaria and Hungary, workers launched “Council Republics” also termed “Soviet Republics,” modeled on the success of factory councils and soviets (congresses of delegates from factory councils) in Russia. These revolutionary attempts were repressed by proto-fascist forces. In Austria, the SDAP maneuvered to politically isolate the more radical Communists and the council movement by steering it into a national representatives structure that the SDAP could control. The councils were defeated as a revolutionary movement, but left lasting imprints on the political and economic structures of the German-speaking world.

The threat posed by the councils of a successful struggle for control in the sphere of production (valorization) led the bourgeoisie to make unprecedented concessions, allowing the more moderate SDAP to write the constitution of the new Austrian republic. The labor laws of the new country included a legalized form of workers councils that persist today in the German-speaking world as as “Betriebsrat,” which have consultation rights with management, and extended suffrage to all workers (men and women).

The SDAP claimed to have revolutionary goals, but would not support a direct seizure of the means of production by workers councils. Instead, they sought to win control of the state through electoral means, with only vague ideas of how to use state power to build socialism. They won a majority in Vienna, but were in the opposition in Austria’s federal government.

With control of the municipal government of Vienna, the SDAP embarked on a strategy of “cultural” change. The construction of housing was a centerpiece of this effort. They used state power to intervene in distribution of capital by imposing steep taxes on luxuries and in particular on luxury housing. They then used the revenues of this tax to build enormous amounts of public housing for workers– 348 complexes housing around 60,000 people by 1934. The Karl Marx Hof is the largest and most well-known of these. Some included novel experiments to collectivize reproductive labor, with centralized kitchens staffed by wage workers replacing the unwaged labor of cooking normally carried out by women.

Red Vienna’s housing was not only part of a cultural strategy of creating new environments for workers to foster a new working class culture, it also served a political and economic anticapitalist strategies. Politically, it establishes voting blocs for socialism across the city.

The economic impact of Red Vienna’s housing projects harder to assess from the standpoint of anticapitalist thought and action. There is no question that the developments dramatically improved life for the working class. At the end of WWI, most workers lived in abominable tenement buildings or even shantytowns. Then as now, the capitalist market was oriented toward luxury housing production. The City responded to this “market failure” by building housing which would remain under municipal ownership, with tenants paying affordable rents. Rent covered maintenance and contributed to construction costs of new developments. Money was exchanged for the use value of the apartment, but the apartment was built to serve use value, not to create surplus value for investors.

The construction was also a job creation mechanism for the government, and in that sense it was a commodity produced by wage labor. However, some workers participated in building housing as volunteers. Their volunteer time would count toward their payment of rent on an eventual apartment unit. Apartments were allocated by a point system that gave housing to each according to their need. While not fully decommodified- workers paid rent for the housing– the apartments were not exchanged on an unregulated market, and were not an investment vehicle, as housing is in the capitalist world.

Of course, Austrian capital did not like paying the heavy taxes of Red Vienna, and was unhappy with how the SDAP was remaking the capital city to put the working class at the center of cultural and social life. In the early 1930s, the conservative Catholic majority in the federal government stripped the city of its rights to levy the taxes that had funded its housing projects. Soon, fascists executed a coup that brought Red Vienna to an end. The Karl Marx Hof was one of the sites of heavy fighting between socialist workers and fascist putschists, but even with a militia of 80,000, the SDAP was unable to defeat the fascists. Most of its leaders were arrested and many members died in concentration camps.

After WWII, socialists once again took control of Vienna’s city government, and continued the building project in more-or-less the same form that the SDAP had begun. Today, over 500,000 people in Vienna live in city-owned housing.

The SDAP stymied worker struggle over valorization by sabotaging the workers councils, and instead sought to use state power to divert distribution of capital to projects that partially decommodified housing for the working class.

At a time when a revolutionary workers movement seems to be out of the question, and control of most federal governments is in the hands of liberals or the right, Red Vienna could hold some clues to how local government can contribute to anticapitalist movements– and the limits of such an approach.

For a more full description of Red Vienna, check out Helmut Gruber’s history: https://libcom.org/library/red-vienna-helmut-gruber

* = italics

I would like to enter the thread of conversation woven by Miryam and Pere, and expanded by Colin and Nicolas. The thread I would like to tease out deals with the precision and context of a series of keywords employed in their linked discussion. Of course many might find such an approach, with its attention to words, yet another pedantic play with verbiage, and thus wrought with the contradictions identified with the Derridean disciple’s tendency for navel-gazing that often reifies the reproduction of a status quo; when rather, we are here concerned about the dominant political economy of our time: capitalism, or more precisely its “anti-” side. However, I think it is useful to be more cautious and measured in the terms we employ, and the set of meanings they are pointing to — both inductively and to the futures they hearken.

By this I mean to say, we might want to take a note from the way Karl Marx structured his first two volumes on Capital, and thus how Engels structured his notes for the third volume: that is, with a deconstruction of the terms by which the socially necessary relationships composing the specific moment, or dimension, of Capital formation — accumulation, exchange, and circulation — have been yoking together elements of a uneven socio-political and ideological terrain. What Stuart Hall called an ‘articulation’, “some arbitrary “fixing”… What is ideology but, precisely, this work of fixing meaning through establishing, by selection and combination, a chain of equivalences” (Hall 1985, p. 93). In my reading of Hall, I don’t believe he meant “arbitrary” in the strong sense but rather to express that hegemony was not pre-determined by some mechanistic social force out-there in the world apart from social interaction and intersubjectivity. I have appreciated the manner in which Harvey has opened up each lecture, for the way each beginning has echoed Marx’s own approach to his study of Capital, in which he began his studies with attention to *hegemonic concepts*: use-value / exchange value in Vol. 1, money (capital) / commodities in Vol. 2, and cost-price / profit in Vol. 3. Marx described this approach, in Vol. 3, as a means for “locating the concrete forms growing out of *the movements of capitalist production as a whole* and setting them forth. In actual reality the capitals move and meet in such concrete form of the capital in the process of production and that of capital in the process of circulation impress one only as special aspects of those concrete forms” (Marx 1909, p. 38). I find Marx’s approach to be if not instructive than a demonstration of what can be understood when diagnostic tools for specifying the historical and material ways keywords, conceptually and in practice, (1) point to particular realities, stand in for those realities, and inform the futures we envision, (2) become the symbolic “ground” on which ideological, and thus practical, struggles are had, and (3) how they have become the general types, social and juridical laws, as well as habits we live by. Karl Marx’s approach I believe differs somewhat from the Raymond Williams approach to historicizing the definition of words, because Marx seemed to place more concern on how these terms were “set forth”, or “put into motion”, by “revealing” the entanglement of hegemonic concepts with the logical conclusion (or dialectics) of their ideal-type and the socially necessary relationships required for their reification. It seems to me David Harvey has in a sense asked us to equally take up this task, in this seminar, for our own conjuncture. Thus, I found myself constantly re-reading the line I quoted from Marx above, and in so doing have found it necessary to remove where Marx placed his italics to emphasise the dynamism of the social laws put into motion by Capital formation and, instead, I have highlighted his peculiar use of capitals, in the plural.

Colin made a rather interesting note about Harvey’s lecture that I too interpreted from his words. That is, there might be a similarity in the study of social phenomena between Karl Marx and Max Weber. They both employ an ideal-type method, which is to say, as Weber once wrote:

Whatever the content of the ideal-type, be be it an ethical, a legal, an aesthetic, or a religious norm, or a technical, an economic, or a cultural maxim or any other type of valuation in the most rational form possible, it has only one function in an empirical investigation. Its function is the comparison with empirical reality in order to establish its divergences or similarities, to describe them with the most unambiguously intelligible concepts, and to understand and example them causally.” (Weber 1949, p. 43)

What I’ve often noticed about Max Weber’s social scientific approach is that he privileges the concepts of the researcher. Prior to the statement above he describes ideal types as drawn from the researchers own morals and ethics, or an ideal-type the researcher constructs in which they have no vested interest in. Karl Marx, on the other hand, and if we accept that he was working with ideal types in the ways described above, began with those ideals — can we saw “concrete forms” or hegemonic concepts — that are linked to the base of economic activity and the center of political struggles. In this way the concepts he identifies are not considered universal, in some space of “homogeneous and empty time”, but are rather concepts that are lived, and hence concepts that do not simply justify (unequal) power relationships but a constitutive dimension of socially necessary relations. In this sense, concepts do not have some novel reality (out-there that we identify and manipulate), rather ideas about Price, Commodity, and Labour, for example, are a product of the metabolic relations prior to them. The brilliance I have always found in reading the volumes on capital, is his insistence on thinking/writing dialectically. Moreover, how Marx analyzed not the ideal types he constructed but those ideal types employed by both vulgar and advanced economists, alike, without losing sight of the socially necessary relationships for their iteration and reiteration. What this allowed Marx to “reveal”, and here I pick up on Stuart Hall’s elaboration on Althusser and Marx over the problem of ideology, is how one-sided David Ricardo and Adam Smith’s analysis of economic activity. We must remember how classical economists wanted to describe the emergence of mercantilism and capitalism as inevitable evolutionary outcomes of social living. Moreover, Marx was also criticizing the more vulgar economists who “confine themselves to systematizing in a pedantic way, and proclaiming for everlasting truths, the banal and complacent notions held by the bourgeois agents of production about their own world, which is to them the best possible one” (Marx 1990, p. 175). Marx identifies how their conceptions of “the economy” were one-sided, while, as Hall notes, “the other “lost” moments of the circuit are, however, unconscious, not in the Freudian sense, because they have been repressed from consciousness, but in the sense of being invisible, given the concepts and categories we are Using” (Hall 1986, p. 37). I am wondering if we can still use Marx’s peculiar approach to the study of Capital formation today? And is it fair to say that we might want to look at concepts such as Price (a term used today, with uncanny features to the concept used by classical economists) and, as well, employ this analytical technique to the words employed by anti-capitalist actors, for example Production?

In this way, I want to piggyback on Miryam’s suggestion that anti-capitalist thought and action will need to account for “new labor forms and working force patterns have resulted from the emergence of a post-industrial economy that has transited from manufacturing to services in the last decades.” However, and I do not mean to be contrarian here, Miryam might we might not want to begin with the conceit, or perhaps the assumption, that the capitalist/worker relationships is an ideal-type that is universal in Capitalist societies? What I mean to suggest is that I would like to open up the terrain Miryam and Austin have pointed us to, by asking: does anti-capitalist thought and action need to question if capitalist/worker relationship as defined by classical economists of the 18th century and employed by vulgar economists of Karl Marx’s time still employ the ideal-types which are in-motion in our current moment? Of course, in many places of the world, classical strategies for connecting labor power to machinery in the production of commodities have some semblance to those employed by the Mississippi, South Seas, and Dutch East India companies, or the Bank of England and De Nederlandsche Bank. Notwithstanding, I am not exactly sure these strategies for accumulation of wealth remain — even though bits-and-pieces of the strategies those monopolies employed remain since the conditions of Capital accumulation find them efficient; for example, slave relations in extractive practices and currency policies by international monetary institutions. Perhaps, the answers to anti-capitalist thought and action are not found in the volumes, per say, since, as Stuart Hall wrote better than I can, Karl Marx “wasn’t in a position to understand modern industrial corporate capitalism because he wasn’t alive in it” (Hall 1983, p. 40). I would go as far as to state that Marx, himself, or rather his writings, have almost nothing to say about rather significant fields of struggle and hegemony that inform the international economic and political regimes that maintain Capital formations currently. Yet, as I have been suggesting, his methodology offered many useful diagnostic tools.

And if I may touch on a few points apart from what has already been discussed in the first week’s threads, I would like to put up for discussion: would it profit anti-capitalist thought to pay closer attention to how ideas of Price and Wealth are currently comprised by the socio-economic and political elites? Or maybe a discussion of the significant of “the economy” in political struggle, since 2008, from a variety of valences?

I think that a closer examination of what these terms mean, currently, might open up a profitable discussion around the ways in which certain individual and collective actions, largely by economic elites, have sought to yoke together conceptions of Price and Wealth that have sought to reiterate a particular conception of classical 17th century economics and to reorganize political and economic activity around, largely, Libertarian and (Neo)Liberal ideas. David Harvey has been particularly significant in detailing the major upheavals in ideologies, often held by economic and political elites. I wonder if what is missing from our discussion, so far, is a sensitivity to the practices by which, and the extent to which, certain durable ideologies around Price and Wealth have facilitated a unified, yet differentiated, class project we can call Neoliberalist? In other words, and I know I am most certainly wrong here, there seems to have been significant scholarship on the interrelationship and interconnections between print-capital, and it’s technologies, with nationalism, and quite a bit of scholarship on the working class — does it exist in-itself? can it exist for-itself in mass form? what about the peasant question? what constitutes a social movement? — but not as much discussion on how communication and information technologies have articulated consent, as Chomsky wrote, and consensus/rule, as Gramsci was concerned.

It seems what is needed is further questioning of the role, and the specific and peculiar formation, of elite classes and species of capital within the upper and middle classes of the OECD countries, as well as the elite classes of countries of the South — Venezuela’s coup attempts, and perhaps in Honduras as well, and Nigerian elite’s reliance on KBR are instructive.

This is all to say that I still find it strange to enter rooms discussing international politics and anti-capitalist movements that do not mention moments like the Nixon’s 1972 visit to “open” China, the repeal of the Telecommunications Act, Chicago-boys, Rockefeller Laws, the creation of credit-default swaps and hedge funds, the deregulation of housing policies away from public and affordable housing, the growth of NATO and Proposition 33, attacks on environmental regulations and extension of cap and trade to air/water/land, oil and civil war in Chad, etc. Have these concurrent and ultimately co-constituting moments remade the relationships between the state, its military, and revenue base with the central monopolies (and their commodities) and what has become the financial class?

The point I am attempting to make is that when anti-capitalist thinkers and organizers take ideal-types directly from Marx’s three volumes, in which he sought to understand the totality of capitalism, from his perspective into how Capital was constructed from industrial manufacturing, and the strategies for accumulation and theoretically eternalized, in Europe from the 17th to 19th centuries, we seem to disavow a discussion of Capitals — in the plural — and the particularities of their formation in our current moment.

So, it seems prudent to question why there remains a tendency to study Labor and the apparatuses important to Neoliberal strategists (think IMF, Federal Reserve, and monetary policy) and not the socially necessary relationships of capital formation that have become integral now — if not having been significant since the early modern period. Certainly speculation in the bond and securities markets matter to the stock markets crashes in 2008, but I am not sure they were as significant as the contradictions in the housing sectors, and the materialities of speculation and bubble bursting, on rearranging the production and consumption of housing and the processes of re-urbanization. Perhaps, Saskia Sassen’s insights into the global dispersal of manufacturing and production that has happened alongside the centralization of corporate headquarters in culturally rich and dense cities. Her insights might help us to further tease out the interrelationships between housing, service sector labor, rises in global cities, and the financial class. While her analysis is not a theory of Capital per say, Sassen provides a window into a different set of relations defining the “core” countries, and perhaps new sets of arrangements necessary to the reproduction of surplus value. Thinking about global cities in this was has caused me to ask: are spatial fixes underway in the recompositioning of urban space connected more to manufacturing/industry or FIRE sectors? And here I think of Buenos Aires and Mumbai over time: how do recomposition of the built environment of these cities fold back into and inform new forms of labor arrangements as Miryam has asked us to think about?

Surprisingly I remain with a few more points, but due to the space I have already occupied I will attempt to be as brief as possible: