[Lead bloggers: Erik Forman, Miryam Nacimento, Youssef Ramez]

In this week’s lecture, Prof. David Harvey outlined a framework for understanding the development of social relations under capitalism as a totality, and used this framework to described the shift to neoliberalism in the late 1970s.

The framework draws on a footnote in Chapter 15 of Vol. 1 of Capital, in which Marx describes the reciprocally deterministic relationship between technology, nature, production, reproduction, social relationship, and the mental conceptions that hold it all together as the totality of life under capitalism. Harvey adds “institutional arrangements” to this list and dubs these “activity spheres” or “moments.” He describes the relationship between these activity spheres as co-evolutionary, but with each maintaining the possibility of transformations that create contradictions and force change across the system. Transformations in each activity sphere that could result from human agency, tendencies immanent within the system, nature, or other impetus.

As Harvey writes in Enigmas of Capital, “if, as Marx once averred, our task is not so much to understand the world as to change it, then, it has to be said, capitalism has done a pretty good job of following his advice.” From responses to labor insurgency, to developing technology to increase extraction of surplus value from workers, dominating nature, or creating new forms of social organization, capital has revolutionized itself again and again.

Prof. Harvey gives us a strong case in point– the neoliberal turn in capitalism of the late 1970s. He describes how the protection of the hegemony of the capitalist class from multiple insurgences and economic stagnation required new mental conceptions and institutional arrangements– which economists like Hayek, Friedman, and the Chicago School were happy to provide. Neoliberal economic doctrine called for the retreat of the state from subsidizing social reproduction, privatization of public services, withdrawal of environmental and labor protections, free trade (no tariffs), essentially a return to laissez-faire economic liberalism. After early test cases in Allende’s Chile and New York City after the 1975 fiscal crisis, neoliberal thought became hegemonic in the IMF and other global financial institutions. Neoliberal economic theory was “instatiated” into common sense of how you are supposed to run a government. Harvey cites a cycle of meetings and conferences in the late 1970s bringing together members of the capitalist class as the locus where neoliberalism as a class project was consolidated.

Neoliberalism has endured now for nearly half a century, but it has been fraught with contradictions and conflict the entire time. While neoliberalism mobilized the rhetoric of freedom and choice, in fact it also resulted in an intensification of state repression of social movements and labor, a core paradox. To maintain hegemony, neoliberal elites are forced to rely on undemocratic tools of governance, such as the WTO and other transnational institutions, discipline labor with the threat of international competition, union-busting, and outright violent repression.

Harvey pointed out that neoliberalism often leads to an increase in nationalism as a backlash against the globalization of capital, often in the form of right-wing populism. This was visible already in the mid-1990s in the UK, but appears to be entering a new phase now with Brexit, Trump, and in Germany the AfD.

Economic contradictions are also a source of volatility, as Harvey illustrates in his description of deregulation of capital flows that led to the 2007/2008 Financial Crisis. While some have claimed that the crisis led to the end of neoliberalism, Harvey claims neoliberalism is alive and well, but has lost legitimacy and justification, with the capitalist class turning increasingly to authoritarianism to cement its rule, winning consent for repression through right-wing populism.

Questions

- Neoliberalism has lost legitimacy without losing power. While a turn to increased authoritarianism to secure the present social relations seems to be in progress, are there other evolutions of the totality we would hope for, and how would we win them?

- Of the activity spheres that Harvey outlines as constituent of the totally of relations under capitalism, which presents the greatest opportunity for intervention, or is it possible or necessary to construct a project that integrates intervention in all or several? Are there historical examples we can look to for inspiration of efforts to break with capitalist social relations?

- Why did Marx privilege the proletariat as an agent of change, and is it predisposed to power to intervene in specific activity spheres over others? Are other subjects more likely to be able to leverage change in the world system today? Why or why not?

- As critics of capitalism, we have a model that describes the totality of capitalist social relations, and can theorize about how events and trends result mutations in the system. In the 1970s, the United States was still close to the zenith of its power, the EU did not yet exist, the state socialist world was “contained” through proxy wars; as a result, the capitalist class was relatively organized and united on a global level and was able to come to a consensus on how to emerge from the crisis of the early 1970s. Today, China has created an alternative set of global financial institutions and arrangements, US hegemony is fading fast, and regional powers are jockeying for position. Capitalism is more global than ever before, but the liberal postwar order has never been weaker and world-systemic chaos is escalating. At this point in history, how and where is capital making decisions, or is history unfolding “behind the backs” of it participants, as Marx would say? What does this mean for efforts to build anti-systemic movements?

- How are we to understand the interplay between the neoliberal corporate elite and the state? If neoliberalism is to be understood as a capitalist class project that has been able to capture the state apparatus revealing its authoritarian nature (against its supposed ideals of freedom, equality and liberation), where could strategic anti-capitalist actions take place? what kind of anti-capitalist action does the authoritarian nature of neoliberalism demand?

I’d like to respond to the last question, concerning the relationship between corporate elites and the state. I think Prof. Harvey’s allusion to the NYC Fiscal Crisis in 1975 was extremely poignant, because it really did cement the framework of our current political situation.

Much like Detroit and more recently Puerto Rico (among other states and cities around the world), the NYC fiscal crisis, provocated by irresponsible lending, bookkeeping, and bond practices in the financial sector (and not, as the popular narrative would suggest, by an overglutted public sector) provided a critical opportunity for an elite coup of state operations, via the Emergency Financial Control Board (Kim Philips-Fein provides an excellent analysis of this history in her book, Fear City). The board systematically shifted resources and attention away from public welfare and towards the cultivation of a financialized sector–the vibrant and politically powerful real estate industry being a lasting hallmark.

The evidence of this coup persists today. Consider the enormous scale of rezonings that occurred during Bloomberg’s administration, which artificially inflated the value of manufacturing land by converting its use value to residential, displacing and ultimately eradicating hundreds of thousands of blue collar jobs. These policies were imagined and facilitated by a branch of the City government that dates to a post-fiscal crisis reality, the Economic Development Corporation, a quasi-public agency that is unelected yet manages the bulk of the City’s assets. One can also see the sale of Manhattan’s West Side to Hudson Yards, or Central Brooklyn, rebranded as “Atlantic Yards”, to see the prevalence of these neoliberal strategies of displacement.

So where in this are opportunities for resistance? Institutionally speaking, it appears to be a long road. The progress on the Atlantic Yards project was stymied for a while by well-coordinated protests at community board meetings, which stalled the legal ULURP process. Neighborhood activists essentially filibustered for months, gaining notoriety and a few hard-fought concessions of affordable housing provision. There are many other moments and organizations that resist the financialization of land via neoliberal governance, and I think that they have definitely served to (at the very least) slow the pace of this process. Whether these are reasonable strategies for visible and meaningful institutional remains to be seen. This also prompts a recurring question of my own–incremental or revolutionary change? One can’t attribute the development of (admittedly problematic and flawed) affordable housing policies in New York to beneficent political leadership–it’s evidence of sustained activism. The affordability crisis has also sparked valuable progress for Community Land Trusts, which de-financialize and stabilize community land holdings and protect affordability in perpetuity. Could tangible achievements like these persuade anticapitalist skeptics?

I’m curious to hear others’ thoughts on the question, of whether or if incremental, institutionalized changes in favor of anticapitalist action can still ultimately fulfill their goals, or does that betray the very nature of anticapitalist action?

Thanks for the summary and the engaging questions! Building off of the first question, I would like to explore the notion of the “totality,” and how we can reimagine this rather rified concept.

The first discussion question reads: “Neoliberalism has lost legitimacy without losing power. While a turn to increased authoritarianism to secure the present social relations seems to be in progress, are there other evolutions of the totality we would hope for, and how would we win them?”

I think it is important to build on the idea that the totality is open to transformation. In this sense, attaching a totality to any particular ideology becomes fraught and leads to inconsistencies. The word “totality” applied to –the–dominant ideology makes it hard to see cracks in its power to motivate action or control resources. After all, capitalism’s control has never been complete and neoliberalism has never enjoyed a pure totality. This is why we can imagine an ideology as losing legitimacy without losing power–because we are thinking only in terms of fixed economic ideologies and whether or not they are dominant. In other words, although the Trump presidency follows neoliberal logics in many important ways, to say that neoliberalism has not lost power denies changes in subjectivity, racial formation, and class relations through OWS, BLM, Kshama Sawant, Ocasio-Cortez, and the unionization of fast food workers. The word “totality” blinds us to the always incomplete nature of ideology.

As a first step towards a more fluid understanding of the relationship between the “moments,” I suggest we think about “totalities.” This is not to suggest that different people live in incommensurable worlds, each of which is complete and coherent. Rather it is to emphasize the ways that the same “moment” can produce different “totalities.” It opens our eyes to movement, contradicion, and fracture. For example, it seems commonsensical to focus on digital technologies as a moment that creates a neoliberal labor force, with Uber as a prime example. However, focusing on totalies in the plural also allows us to see how these same technologies informed the logics and pragmatics behind movements, not only against neoliberalism, but also ones that envision new futures. (Juris 20120 “Reflections on #OccupyWallStreet).

I’m intrigued by Austin’s discussion of the connection between totality and ideology. In my understanding of Harvey’s lecture, the concept of ‘totality’ is not meant to be “applied to the dominant ideology,” but rather the dominant ideology must be situated within the totality. Harvey explains that what we understand as neoliberalism coalesced through a variety of transformations across different moments in the totality: the upper class somewhat on the run and looking to change things in the realm of social relations; the purge of Keynesian economics in favor of Hayek/Friedmanites in the realm mental conceptions; mental conceptions which become enshrined in institutional moments such as the IMF and World Bank’s aggressive implementation of structural adjustment programs.

Perhaps one of my colleagues who is better versed than I am on the topic of ideology can chime on where and indeed whether we can neatly fit ideology into the totality framework. It seems to me that ideology would be working across multiple moments, both being imposed from above (flowing out of a class project in the form of institutions like the IMF and ideological projects such as conservative think tanks, exemplified by the heritage foundation) and being to some extent organically reproduced by the material conditions of people’s everyday lives- this is where the Foucauldian ideas of Governmentality and people becoming neoliberal subjects who are Entrepreneurs of the Self come into play.

The more pertinent point is that, understood un-mechanistically, the totality need not be pluralized to be understood as rife with contestation and contradictions. Dynamics are frequently in contradiction with each other across and within different moments, and each of these moments is understood to be fluid, in motion, and constantly changing in a system of feedbacks with the other moments in the totality. The key here is, to quote Harvey, “if you transform any one ‘moment’ but not any of the others, you probably won’t get too far.” Here I’m thinking about the gap between the liberatory possibilities early internet users imagined might arise from the technological leap, to the intensive surveillance, capitalization, and privatization of the internet that has arisen since. The technology changed, but without corresponding transformations in the other moments, the time when it seemed like the internet might engineer us to a better future seems long past. This is not to suggest that all is lost, of course: as Austin’s Juris (2012) article suggests, the internet itself remains a space of contradiction, one that still retains potentialities for new forms of organizing even as it is increasingly privatized and integrated into the surveillance state. And as Austin’s Uber example demonstrates, the internet has transformed the other moments in the totality, producing new contradictions and disruptions. I hope this demonstrates why, for me, the concept of totality retains space for the sort of movement, contradiction, and fracture Austin rightfully suggests we should focus our analyses on.

Its certainly true that “capitalism,” “the capitalist class,” and “the working class” are not monolithic entities. There are all kinds of contradictions within these categories. And the capitalist mode of production (itself composed of contradictions) is always unstable and subject to explosive transformations.

In his lecture, Harvey offered a theory to understand why social change (or stability, however contingent) happens at all. His “totality” – the extremely complex, dialectical relationship between nature, production, reproduction of daily life, mental conceptions, institutional arrangements, social relations, and technology – is the pivot upon which power turns. There are endless “ideas” out there, but only some of them gain sufficient power to compel people to do what they wouldn’t do otherwise. Through his analysis of the neoliberal turn, Harvey helps us understand that social change cannot be achieved by intervening in just one of the above “moments” within the totality. One can argue ad nauseum (and compellingly) for collective ownership of the means of production. But this alone will accomplish nothing. It is necessary to build institutions, to transform social relations, etc. in order to mobilize new mental conceptions, transform our relationship to nature, etc.

I would like to briefly respond to the following idea:

“As a first step towards a more fluid understanding of the relationship between the “moments,” I suggest we think about “totalities.” This is not to suggest that different people live in incommensurable worlds, each of which is complete and coherent. Rather it is to emphasize the ways that the same “moment” can produce different “totalities.” It opens our eyes to movement, contradiction, and fracture. For example, it seems commonsensical to focus on digital technologies as a moment that creates a neoliberal labor force, with Uber as a prime example. However, focusing on totalities in the plural also allows us to see how these same technologies informed the logics and pragmatics behind movements, not only against neoliberalism but also ones that envision new futures. (Juris 2012).”

I want to respond directly to this provocation, and I do apologize if my brief commentary overlaps with discussion points already made in response. And since I am coming to this commentary with the benefit of hindsight, I will direct my critical gaze less on perceived weakness, and instead on the possibilities and delimitation of thinking about totality, or “totalities” as we have been provoked.

If I am not mistaken, we have been asked to recast the concept of totality, as mentioned by David Harvey in his lectures on the logic and processes of Capital, into a more fluid (or open?) metaphor for considering “movement, contradiction, and fracture.”

Though I am not so certain these metaphorics are necessary. While I agree that understanding how something resembling a neoliberal labor force and, also, the Occupy movement must be considered in terms of the new medias through which they have been articulated – and the extent to which virtual spaces have functioned as vital points of convergence/divergence, as well as consensus/consent – I am not sure the anchor for the notion of “totalities” offered, above, shares the same point of reference and, thus, insight as the notion of “totality” which David Harvey often pinpoints as a key aspect of Karl Marx’s writings on Capital.

I am also just as pessimistic about the pursuit of defining in total terms – or molar/major, as Deleuze might quip – is as useful either, which I will return to in a moment. And it must also be said: the Occupy movement has, in a Ricœurean sense, set into motion concepts, like the 99%, which have been proven beneficial for intervening into dominant narratives with an easy idea that points to suppressed histories and politics and an easy image for invoking the masses produced by the 1%… now increasingly the .01%. However, the new vistas onto which the notion of the 99% orientate us seems rather limiting; and I am not so sure Occupy – as itself a movement aiming to be in its being: conceptual – has become synonymous with a new-found logics for (political) aggregation. Certainly, Occupy and the 99% have become popular, but perhaps not as empowering since what is figured through each metaphor is diacritically broad and limiting.

The, seeming, theriac to the ideological delimitations of metaphorizing which dramatizes the silenced narratives of the “masses” and decentralized organizing (of both by labor and resistance) is to, first, identify the contours of a “totality” that has historically and organically emerged from the relationships necessary for producing, realizing, and circulating value extracted from (material) dispossession and exploitation. And secondly, we can then gather around this concept of “totality” because it facilitates a shared understanding, and thus the possibility of organic solidarities and fine-grained analysis of contradictions within the system of capital accumulation and valorization.

Yet, to the latter point, the history of class speaks to the delimitations of this approach as well. By this, I mean the history of the term which exceeds even Raymond Williams’ (2014) keyword and is associated with the struggle over the hegemonic concepts for economic and political analysis that arose concomitantly with bourgeoise-life during the 19th century (see Hont 2005). The history of the concept of “class” is instructive, and can function as a warning about spending too much energy with pinning down (like butterflies) a term to a singular and universal definition, and its categories of order.

And, lastly, on this point, my own writing about the delimitations of metaphorical play and “more serious” classification is, admittedly, depoliticizing. What I have done so far is merely, and only partially, disassembled some concepts. The point is, then, to be reconstructive. Yet, I want to engage a reconstructive exercise, as Stuart Hall asked, “with the utmost care… through the narrow passage which separates the old Scylla… from the new Charybdis” (Hall 2000, p. 83). And I would like to begin this reconstructive work with a provocative premise of my own: there is no such thing as a totality.

Of course, we are here because of Karl Marx, who was wholly invested in understanding the “totality” of the Capital form and its formation. What he meant by “totality” I am not exactly sure, but I would like to offer an approximation by doing something becoming all to radical nowadays, by, first, reading his primary texts and, second, without adult supervision.

Below I have a few snippets I pulled from Volumes I, II, and III of Karl Marx’s critique of political economy, and as well lesser his lesser-read dissertation on Democritus and Epicurus and his unfinished manuscript on the history of the concept of surplus-value. I have always found it strange that Marx had called this project a critique of “political economy”, as if his goal was to unsettle the very notion of politics and economy; and perhaps a the notion that the very concept “political economy” is bankrupt. But in re-reading these volumes, I found that “political economy” was used largely in two manners: to name a discourse or its discussants. The “political economy” discourse which became synonymous with Capital, and the capitalists and political economists who celebrated “political economy” as natural, eternal, and sacred. With a similar methodology, I have explored how “totality” was used, textually, by Marx, with inspiration from Cedric Robinson’s outline for an anthropology of marxism.

Jumping right in, totality appears quite earlier in Volume I. In Karl Marx’s preface to the first edition, as he explains his plans for his larger project:

“The second volume of this work will deal with the process of the circulation of capital (Book II) and the various forms of the process of capital in its totality (Book III), while the third and last volume (Book IV) will deal with the history of the theory.” (p. 93)

It would seem that Marx’s intention was to write Volumes I and II as fragments for understanding a larger totality which would be reconstructed in Volume III. However, as will become apparent such a project while intended, nonetheless, does not exhaust “totality” for Marx. This becomes apparent in the chapter on “The Dual Character of the Labour Embodied in Commodities.” Broadly speaking, in this chapter, Marx is examining the passage of an object of utility into a valuable object once realized in exchange, which reiterates his initial exploration, in Vol. I, of the use-value and exchange-value of an object, or commodity. Marx states,

“The totality of heterogeneous use-values or physical commodity ties reflects a totality of similarly heterogeneous forms of useful labour, which differ in order; genus, species and variety: in short, a social division of labour. This division of labour is a necessary condition for commodity production, although the converse does not hold; commodity production is not a necessary condition for the social division of labour.” (p. 132)

Totality then is an assumption about the extent to which differences between the utility of physical objects are connected to concrete differences of productive labor. Assuming these differences are vast and have the potential for producing multiple kinds of objects and necessary labor, then allows for a comparison of forms, in general: physical object and concrete labor, and thus what can and cannot be exchanged properly. As Marx, says prior, a coat cannot be exchanged for a coat, and the same holds true for its labor. Marx goes on to say, in a subsection on “The Commodity”:

“Similarly, the specific, concrete, useful kind of labour contained in each particular commodity-equivalent is only a particular kind of labour and therefore not an exhaustive form of appearance of human labour in general. It is true that the completed or total form of appearance of human labour is constituted by the totality of its particular forms of appearance. But in that case, it has no single, unified form of appearance.” (p. 157)

Thus, in committing to following “totality,” I have come to read this passage as distinguishing between total form and totality. In so doing, Marx critiques the “defects in the total or expanded form of value,” which as noted above can only be considered in its total form as a manifold appearance that, as I see it, contradicts the very premise of totality. Yet, Marx remains curiously committed to exploring the totality of a commodity and of commodity exchange, because it allows for a discussion of “the change in form” of commodities that can only happen when two commodities “confront” each other in an exchange relationship. As he notes about the transformation of gold into an equivalent of money-value:

“If we keep in mind only this material aspect, that is, the exchange of the commodity for gold, we overlook the very thing we ought to observe, namely what has happened to the form of the commodity, We do not see that gold, as a mere commodity, is not money, and that the other commodities, through their prices, themselves relate to gold as the medium for expressing their own shape in money… In this opposition, commodities as use-values confront money as exchange-value. On the other hand, both sides of this opposition are commodities, hence themselves unities of use-value and value… This is the alternating relation between the two poles: the commodity is in reality a use-value; its existence as a value appears only ideally, in its price, through which it is related to the real embodiment of its value, the gold which confronts it as its opposite. Inversely, the material of gold ranks only as the materialization of value, as money. It is therefore in reality exchange-value. Its use-value appears only ideally in the series of expressions of relative value within which it confronts all the other commodities as the totality of real embodiments of its utility. These antagonistic forms of the commodities are the real forms of motion of the process of exchange” (p. 199).

At this moment of transformation, from a physical object into a valuable commodity, not only requires an idealization of a physical object – a fetishization – that is concomitant with the various ways an object can be considered valuable. In other words, gold is far more valuable if it can be exchanged with more than just currencies when it can be shaved down and traded for timber, cotton, wool, sugar, or whale fat. This was far more feasible prior to the invention of a floating currency. We currently use green sheets of paper to make these exchanges, hence the fascination with swimming in a bed of paper dollars. Maybe pushing together Scrooge McDuck’s daily swim in oceans of gold coins alongside Huell Babineaux’s desire to lay on a pile of cash could provide a more tangible imagery; notably in neither case is paper money or gold coins absent. Thus, what is brought to our attention is how idealized value rises most high in relationship to confrontations of utility and exchange, in their totality.

But, as we now come to the realize the applicability of totality to situate an abstraction of value from a physical object, which nevertheless folds back into and informs its valuation, Karl Marx makes a curious not of the delimitation of totality. This comes about in his discussion on the role of machinery to the means and process of production:

“means of production never transfer more value to the product than they themselves lose during the labour process by the destruction of their own use-value. If an instrument of production has no value to lost… It helps to create use-value without contributing to the formation of exchange-value…. Suppose a machine is worth £1,000, and wears out in 1,000 days. Then every- day one-thousandth of the value of the machine is transferred to the day’s product. At the same time the machine as a whole continues to take part in the labour process, though with diminishing vitality. Thus it appears that one factor of the labour process, a means of production, continually enters as a whole into that process, while it only enters in parts into the valorization process. The distinction between the labour process and the valorization process is reflected here in their objective factors, in that one and the same means of production, in one and the same process of production, counts in its totality as an element in the labour process, but only piece by piece as an element in the creation of value” (p. 312).

Returning to coats might help make this clear. A coat is a transformation of an animal’s hide into leather, of a sheep’s wool into yarn and the refining of crude oil into polyester. These materials are further transformed from leather strips, balls of yarn, and polyester fabric into a combination we can use as a winter coat to shield our bodies from the cold. If handmade, these coats can be refined based on the skill acquired by the maker, and thus value can is associated with either the quality perceived in the coat or simply because one associates the maker with quality. But in the age of machinery, coats are made are refined by ever more elaborate and expensive machines which thus make ever more elaborate and expensive coats. Though rarely do we ever know the machine which makes our coats, we instead associate quality and value with the brand which, in turn, buys the machines and labor necessary to produce quality, and fashionable coat. And so the totality of machinery is its situatedness as a means of producing kinds of coats and as acting in conjunction with human labor at a particular moment in the process of physical objects becoming commodities. The totality of this machinery, though, as Marx argues, is only preserved in the commodity in a piece-meal fashion. In terms of value, machinery is fragmented.

We get another view of totality in the chapter on “The Process of Accumulation of Capital”:

“we have seen that simple reproduction suffices to stamp this first operation, in so far as it is conceived as an isolated process, with a totally changed character… It is indeed a well-known fact that the sphere of labour is not the only one in which primogeniture works miracles. To be sure, the matter looks quite different if we consider capitalist production in the uninterrupted flow of its renewal, and if, in place of the individual capitalist and the individual worker, we view them in their totality, as the capitalist class and the working class confronting each other. But in so doing we should be applying standards entirely foreign to commodity production” (p. 732)

“We have seen that even in the case of simple reproduction, all capital, whatever its original source, becomes converted into accumulated capital, capitalised surplus-value. But in the flood of production all the capital originally advanced becomes a vanishing quantity (magnitudo evanescens, in the mathematical sense), compared with the directly accumulated capital… Hence, the political economists describe capital in general as “accumulated wealth” (converted surplus-value or revenue), “that is employed over again in the production of surplus-value,” and the capitalist as “the owner of surplus-value.” It is merely another way of expressing the same thing to say that all existing capital is accumulated or capitalised interest, for interest is a mere fragment of surplus-value.” (p. 734)

In these passages, totality is placed within an entirely novel situation, as compared to its previous use. Totality, here, names the total relationships of individual workers and individual capitalists within the classes required for the production of commodities. And in this perspective, and in this light, Karl Marx comes to a rather convincing conclusion about surplus-value, which does not avoid the term but rather resituates the concept of surplus-value within the processes that bring together busy activity of paper-pushing capitalists, the physical toll of working on the factory floor, and the seemingly beneficial act of buying things with money.

To be honest, I this is where my reading of totality has remained for quite some time. For me, it remained equally hazy until I came across Karl Marx’s dissertation which includes a discussion of Ancient Greek philosophers speculating on the atom and thus physics of their cosmos. In re-reading Marx’s dissertation for totality, there seems to be a clearer picture as to what the term does for him.

In my estimation, Marx’s dissertation is a thorough, yet unorganized and incomplete, critique of the philosophical tradition that was systematized in Ancient Greece. The form of philosophizing which then centuries later was resuscitated during the Renaissance. While the famous men of Ancient Greek philosophy pondered what an atom resembled, or looked like, in its pure-form, we get from Marx a critique squarely focused on relationship between form and its totality, and as well on the form of thinking that characterized the dominant strands of Ancient Greek philosophy in terms of the actions, function, and social consequences of these manners.

He gets to this critique most pointedly when looking at how the atom was theorized by Epicurus as he considered an atom in, as Marx suggests, its “abstract individuality”:

“Finally, where abstract individuality appears in its highest freedom and independence, in its totality, there it follows that the being which is swerved away from, is all being., for this reason, the gods swerve away from the world, do not bother with it and live outside it.”

Marx is making a rather simple point, no matter the complexity of the thought written down by Epicurus, what he was doing conceptually from the standpoint of the concept’s embodiment in Epicurus’ thinking was describing the very fundaments of the physics through generalities that refer back to other generalities. Epicurus was in other words was attempting to describe the most physical aspect of the material world through abstractions of other abstractions, of the atom through the notion of pure-form. Such a practice was personified in Greek mythology as well, in its production and intertextually.

Furthermore, Marx’s frames his dissertation as asking this question:

“Is it an accident that these systems in their totality form the complete structure of self-consciousness? And finally, the character with which Greek philosophy mythically begins in the seven wise men, and which is, so to say as its central point, embodied in Socrates as its demiurge — I mean the character of the wise man, of the Sophos — is it an accident that it is asserted in those systems as the reality of true science?

“It seems to me that though the earlier systems are more significant and interesting for the content, the post-Aristotelean ones, and primarily the cycle of the Epicurean, Stoic and Sceptic schools, are more significant and interesting for the subjective form, the character of Greek philosophy. But it is precisely the subjective form, the spiritual carrier of the philosophical systems, which has until now been almost entirely ignored in favour of their metaphysical characteristics.”

“I shall save for a more extensive discussion the presentation of the Epicurean, Stoic and Sceptic philosophies as a whole and in their total relationship to earlier and later Greek speculation.”

Rather, Karl Marx is most interested in the subjectivity behind these seemingly abstract and pure forms. The atom, as the Ancient Greek philosophers considered it, were ultimately speculations, but of a specific kind, speculations as an atom apart from everything else, in its supposed purity. And thus the atom in a peculiar totality which assumes purity; and thus the atom outside the totality of lived experience, the out-there so to say. To understand the “subjective form” of this way of thinking thus, as Marx notes above, is to consider Ancient Greek philosophies “as a whole and in their total relationship to earlier and later Greek speculation.”

Since it was assumed that the pure-form of the individual atom could only be in its totality, in contradictory terms to an atoms total relationships in the world:

“The concept of the atom is therefore realised in repulsion, inasmuch as it is abstract form, but no less also the opposite, inasmuch as it is abstract matter; for that to which it relates itself consists, to be true, of atoms, but other atoms. But when I relate myself to myself as to something which is directly another, then my relationship is a material one. This is the most extreme degree of externality that can be conceived. In the repulsion of the atoms, therefore, their materiality, which was posited in the fall in a straight line, and the form-determination, which was established in the declination, are united synthetically.”

With the dialectical synthesis of the atom, in its pure form, in view, then Marx’s following philosophical conclusions about Ancient Greek philosophy is not as perplexing:

“The purpose of action is to be found therefore in abstracting, swerving away from pain and confusion, in ataraxy. Hence the good is the flight from evil, pleasure the swerving away from suffering.”

And finally, Marx seems to have written this dissertation as a means to correct Hegel’s misrecognition of the importance of philosophical speculating, on the shape of the atom, among Ancient Greek philosophers, as a constitutive element:

“[Hegel] the giant thinker was hindered by his view of what he called speculative thought par excellence from recognising in these systems their great importance for the history of Greek philosophy and for the Greek mind in general. These systems are the key to the true history of Greek philosophy.”

Karl Marx, in his doctoral thesis, makes explicit the relationship between (pure) forms and the material totality they are enmeshed but render transparent. And, thus, he argues this dyad is worth examining, a methodology we see in his later writings. Although, I stray from making any claims about a direct corollary between “young” Marx and his more “mature” self. Instead, I want to bring attention to Marx’s insistent search for what processes explain the negation of a negation, especially as these processes pertain to idealizing abstractions spiraling away from the world but nevertheless fold back into and inform how material relationships are perceived, analyzed, and described. Thus, it would hold that idealized notions of “totality” would not be his pursuit.

This is an aspect of the no-thingness of “totality” is evident in Volume II. In this volume, his analysis shifts from the stage of commodity production to the realization of the commodity-form, and thus value, by examining the manifold and aggregated transformations of the commodity-form in circuits of exchange. Still, totality remains necessary to name:

“Within the general circulation, C’ functions for example as yarn, simply as a commodity; but as a moment of the circulation of capital it functions as commodity capital, a form that the capital value alternately assumes and discards. When the yarn is sold to the merchant it is removed from the circuit of that capital whose product it is, but still continues as a commodity in the orbit of general circulation. The circulation of this mass of commodities continues, even though it has ceased to form a moment in the independent circuit of the capital of the spinner. The really definitive metamorphosis of the mass of commodities thrown into circulation by the capitalist, C-M, its final abandonment to consumption, can thus be completely separated in time and space from the metamorphosis in which this mass of commodities functions as his commodity capital. The same metamorphosis that has already been accomplished in the circulation of this capital remains still to be completed in the sphere of the general circulation. Nothing is changed if the yarn now enters the circuit of another industrial capital. The general circulation includes the intertwining of the circuits of the various independent fractions of the social capital, i.e. the totality of individual capitals, as well as the circulation of those values that are not placed on the market as capital, in other words those going into individual consumption.” (p. 149-150)

By examining the movements of commodities, or their stalling, within circuits of exchange within the domain of trade and production, Marx is able to derive a picture of how a single ball of yarn transform from a product of production into a mass of commodities on the “open” market which then can in stock market become partial basis of finance capital. Yet, what Marx does not want to lose sight of, and what makes Capital so difficult to read, is that he is attempting to explain the commodity at particular moments, and in so doing as something static, when in fact the commodity-form is what it is because commodities are always moving; say from the land into the factory, from the factory into delivery truck, from the delivery truck to a manufacturer and into another delivery truck, and then into as a collection in a storefront which is a circuit that happens in parallel to capitalists who take out a loan to buy machinery and labor, then sell their product to a merchant who then … I think you get the picture. Totality is then not a thing, but rather names an objective immaterial relationship, or more precisely names a methodology that does not forget that the objective immaterial relationships which allow for industrial capital to be formed is never apart from the objective immaterial relationships which allow for finance capital to be formed. Yet, at no point, is the abstract noun (i.e. “ity”) ever explained in its entirety since doing so would require a form of thinking that idealizes the “totality” in an abstract form that Marx wants to avoid.

Although, Marx did not shy from using analogies and comparisons to paint a picture of what he meant by totality. In this passage, on the

“It is here businessmen who face each other here, and ‘when Greek meets Grek then comes the tug of war,’ The change of state costs time and labour-power, not to create value, but rather to bring about the conversion of the value from one form into the other, and so the reciprocal attempt to use this opportunity to appropriate an excess quantity of value does not change anything. This labour, increased by evil intent on either side, no more creates value than the labour that takes place in legal proceedings increases the value of the object in dispute. This labour – which is a necessary moment of the capitalist production process in its totality, and also includes circulation, or is included by it – behaves somewhat like the ‘work of combustion’ involved in setting light to a material that is used to produce heat. This work does not itself produce any heat, although it is a necessary moment of the combustion process. For example, in order to use coal as a fuel, I must combine it with oxygen, and for this purpose transform it from the solid into the gaseous state (for carbon dioxide, the result of the combustion, is coal in this state: F.E.), i.e. effect a change in its physical form of existence or physical state. The separation of the carbon molecules that were combined into a solid whole, and the breaking down of the carbon molecule itself into its individual atoms, must precede the new combination, and this costs a certain expenditure of energy which it not transformed into heat, but rather detracts from the heat. When the commodity owners are not capitalists, but rather independent direct producers, the time they spend on buying and selling is a deduction from their labour time, and they therefore always seek (in antiquity, as also in the Middle Ages) to defer such operations to feast days.” (p. 208)

Totality takes on a different methodological import in this passage: since now we can assume totality can name what is outside an abstract form, we can then stage the totality, in this case of the capitalist production process, in terms of what is necessary to it. Yet, this “it” is no-thing, but rather a form named so we can name its variously relevant processes, like as is done when understanding the combustion process and the various stages between liquid, gas, and solid of the carbon molecule, and its atoms.

But then, Marx was never solely concerned kicking out the latter holding up the ladder of political economy (as a concept). Instead, he focuses on Capital, itself, and how it is formed processurally so as to gain a picture of how it fold back into and shape social classes, relationships (intimate and structural), ideologies; what he termed “total social capital”:

“the constant repetition of the process of production is the condition for the transformations that the capital undergoes over and again in the circulation sphere, for its alternately presenting itself as money capital and as commodity-capital. But each individual capital forms only a fraction of the total social capital, a fraction that has acquired independence and been endowed with individual life, so to speak, just as each individual capitalist is no more than an element of the capitalist class. The movement of the social capital is made up of the totality of movements of these autonomous fractions, the turnovers of the individual capitals. Just as the metamorphosis of the individual commodity is but one term in the series of metamorphoses of the commodity world as a whole, of commodity circulation, so the metamorphosis of the individual capital, its turnover, is a single term in the circuit of the social capital… The circuits of the individual capitals, therefore, when considered as combined into the social capital, i.e. considered in their totality, do not encompass just the circulation of capital, but also commodity circulation in general.” (p. 427-428)

And so, totality is not, as I’ve heard critiqued of Marx, about naming some totalizing image of capitalist society or capitalism, but rather the interrelatedness and interconnectedness between objective immaterial relationships and the abstract forms of thinking and concepts that inform them, especially those ideas of value which shape the contours of Capital and, thus, the socially necessary relationships needed to hold up such a ridiculous economic idea.

Though, it was in Volume III, as Marx stated, in which he was going to demonstrate the “totality.” However, this volume did not reach the level of completion of volume II, and Marx’s ideas are difficult to tease out. Yet, there remain interesting ways thinking with totality was integral for Marx.

For example, when Marx discussed distributions and disconnections associated with price, surplus-value, and their relationship:

“Between those spheres that approximate more or less to the social average there is again a tendency to equalisation, which seeks a possibly ideal mean position, i.e., a mean position which does not exist in reality. In other words, it tends to shape itself around this ideal as a norm. In this way there prevails, and necessarily so, a tendency to make production prices into mere transformed forms of value, or to transform profits into mere portions of surplus-value that are distributed, not in proportion to the surplus-value that is created in each particular sphere of production, but rather in proportion to the amount of capital applied in each of these spheres, so that equal amounts of capital, no matter how they are composed, receive equal shares (aliquot parts) of the totality of surplus-value produced by the total social capital.”

Only by understanding the existence of a totality can Marx explain the amount of capital preserved in the rate of profit outside of production, because he is aware surplus-value achieved in production is related to market prices and market values. From my reading, the totality under scrutiny in Volume III, then, is that of surplus-value.

As Marx explains:

“The whole difficulty arises from the fact that commodities are not exchanged simply as commodities, but as the products of capitals, which claim shares in the totality of surplus-value in proportion to their magnitude, demanding equal shares for equal sizes. And the total price of the commodities that a given capital produces in a given period of time has to satisfy this demand. The total price of these commodities, however, is simply the sum of the prices of the individual commodities, which form the product of the capital in question.”

“This by no means follows necessarily, and it is asserted only because the distinction between the value of commodities and their price of production has as yet not been understood. We have already seen that the price of production of a commodity is not at all identical with its value, although the production prices of commodities, when considered in their totality, are governed only by their total value, and although the movement of production prices for commodities of different kinds, all other circumstances remaining the same, is determined exclusively by the movement of their values. It has been shown that the production price of a commodity may stand above or below its value, and will only coincide with it in exceptional cases. But the fact that agricultural products are sold above their price of production by no means proves that they are also sold above their value; just as the fact that industrial products are sold on average at their price of production does not show that they are sold at their value. It is possible for agricultural products to be sold above their price of production and below their value, just as many industrial products yield their price of production only because they are sold above their value.”

Marx’s thoughts, in volume III, might be a bit difficult to wrap our heads around, but when placed within the context of the fourth volume, Marx had planned to write about the history of the concept of surplus-value, his desire to explain inner-workings of the creation of value is brought into high relief.

Interestingly, in Theories of Surplus-Value, Marx begins to insert different figures of society into his analysis, more explicitly:

“production cannot be separated from the act of producing, as is the case with all performing artists, orators, actors, teachers, physicians, priests, etc. Here too the capitalist mode of production is met with only to a small extent, and from the nature of the case can only be applied in a few spheres. For example, teachers in educational establishments may be mere wage-labourers for the entrepreneur of the establishment; many such educational factories exist in England. Although in relation to the pupils these teachers are not productive labourers, they are productive labourers in relation to their employer. He exchanges his capital for their labour-power, and enriches himself through this process. It is the same with enterprises such as theatres, places of entertainment, etc. In such cases the actor’s relation to the public is that of an artist, but in relation to his employer he is a productive labourer. All these manifestations of capitalist production in this sphere are so insignificant compared with the totality of production that they can be left entirely out of account.” (p. 411)

“The workmen who function as overseers of those directly engaged in working up the raw material are one step further away; the works engineer has yet another relation and in the main works only with his brain, and so on. But the totality of these labourers, who possess labour-power of different value (although all the employed maintain much the same level) produce the result, which, considered as the result of the labour-process pure and simple, is expressed in a commodity or material product; and all together, as a workshop, they are the living production machine of these products—just as, taking the production process as a whole, they exchange their labour for capital and reproduce the capitalists’ money as capital, that is to say, as value producing surplus-value, as self-expanding value.” (p. 411)

“It is indeed the characteristic feature of the capitalist mode of production that it separates the various kinds of labour from each other, therefore also mental and manual labour—or kinds of labour in which one or the other predominates—and distributes them among different people. This however does not prevent the material product from being the common product of these persons, or their common product embodied in material wealth; any more than on the other hand it prevents or in any way alters the relation of each one of these persons to capital being that of wage-labourer and in this pre-eminent sense being that of a productive labourer. All these persons are not only directly engaged in the production of material wealth, but they exchange their labour directly for money as capital, and consequently directly reproduce, in addition to their wages, a surplus-value for the capitalist, their labour consists of paid labour plus unpaid surplus-labour.” (p. 411-412)

What Marx rendered evident, in his critique of political economy, which he spread out over four incomplete volumes, was how the unity among different forms of material and immaterial labor, within the context of a totality, is misrecognized by political economists, and their idealized understanding of value, surplus-value, and political economy. Such an analsysis, from my perspective, is invaluable for understanding our current conjuncture, especially in the wake of the market crashes after the summer of 2007. And it rests on situating forms within their totality while restraining from a idealizing of totality, as a form unto itself. Thusly, the project of theorizing totality without reifying any concept as being total, and in so doing avoiding the penchant for one’s own thinking to be totalize the object under consideration, is not resolved by supplementing totality with totalities, because such an enterprise does not change one’s relationship to the act of theorizing. In other words, it doesn’t matter if Democritus or Epicurus had theorized atoms rather than an atom since the act of theorizing atoms apart from their totality is akin to theorizing an atom apart from its totality.

In short, it seems to be totality names, on one hand, a dialectical valence (and praxis perhaps) and, in the other hand, the manifold conditions necessary for there to be such an appearance of form, including most importantly the standpoint of the actors under examination and examiner doing the analysis. Totality is, thusly, not a thing. And in so far as totality is no-thing – because totality is conditioning, conditional, and the condition – attempting to hold totality in view as an “it” is contradictory, and the same holds true if pluralizing the term.

This is why I have been suspicious of Antoino Negri’s writings on totality. While I have long been enamored with his dexterity in conceiving the spatial totality that is Empire, Negri’s project seems to lead us to a dubious political and theoretical standpoint. This has, in my opinion, has to do with his methodology, specifically his desire to historicize totality, or the totalities of power always latent (or virtual) in the biopolitical: from the totalizing sovereign (king) to the (modern) sovereign state and totalitarianism (see Negri & Hardt 2000, p. 67-113). Such a historical enterprise is possible, if and only if, totality is considered a level of sorts unto which certain theoretical forms – naming obtuse notions about broad socio-systemic relationalities – can be situated. Moreover, a level over and above the mundane world, a level of the everything at once. On paper, this may very well be so. However, in practice how is a politics that “conceives the future only as a totality of possibilities that branch out in every direction” (p. 380) possible? And here I will let Negri elaborate:

“We should emphasize that we use ‘‘Empire’’ here not as a *metaphor, which would require demonstration of the resemblances between today’s world order and the Empires of Rome, China, the Americas, and so forth, but rather as a *concept, which calls primarily for a theoretical approach. The concept of Empire is characterized fundamentally by a lack of boundaries: Empire’s rule has no limits. First and foremost, then, the concept of Empire posits a regime that effectively encompasses the spatial totality, or really that rules over the entire ‘‘civilized’’ world. No territorial boundaries limit its reign. Second, the concept of Empire presents itself not as a historical regime originating in conquest, but rather as an order that effectively suspends history and thereby fixes the existing state of affairs for eternity… From the perspective of Empire, this is the way things will always be and the way they were always meant to be. In other words, Empire presents its rule not as a transitory… Third, the rule of Empire operates on all registers of the social order extending down to the depths of the social world. Empire not only manages a territory and a population but also creates the very world it inhabits… thus Empire presents the paradigmatic form of biopower. Finally, although the practice of Empire is continually bathed in blood, the concept of Empire is always dedicated to peace—a perpetual and universal peace outside of history… (p. xv)

“The twentieth-century theorists of crisis teach us, however, that in this deterritorialized and untimely space where the new Empire is constructed and in this desert of meaning, the testimony of the crisis can pass toward the realization of a singular and collective subject, toward the powers of the multitude. The multitude has internalized the lack of place and fixed time; it is mobile and flexible, and it conceives the future only as a totality of possibilities that branch out in every direction. The coming imperial universe, blind to meaning, is filled by the multifarious totality of the production of subjectivity. The decline is no longer a future destiny but the present reality of Empire… (p. 380)

“We can answer the question of how to get out of the crisis only by lowering ourselves down into biopolitical virtuality, enriched by the singular and creative processes of the production of subjectivity. How is a rupture and innovation possible, however, in the absolute horizon in which we are immersed, in a world in which values seem to have been negated in a vacuum of meaning and lack any measure? Here we do not need to go back again to a description of desire and its ontological excess, nor insist again on the dimension of the ‘‘beyond.’’ It is sufficient to point to the generative determination of desire and thus its productivity. In effect, the complete commingling of the political, the social, and the economic in the constitution of the present reveals a biopolitical space that—much better than Hannah Arendt’s nostalgic utopia of political space— explains the ability of desire to confront the crisis.19 The entire conceptual horizon is thus completely redefined. The biopolitical, seen from the standpoint of desire, is nothing other than concrete production, human collectivity in action. Desire appears here as productive space, as the actuality of human cooperation in the construction of history. This production is purely and simply human reproduction, the power of generation. Desiring production is generation, or rather the excess of labor and the accumulation of a power incorporated into the collective movement of singular essences, both its cause and its completion” (p. 388).

“To confirm this hypothesis, it is sufficient to look at the contemporary development of the multitude and dwell on the vitality of its present expressions. When the multitude works, it produces autonomously and reproduces the entire world of life. Producing and reproducing autonomously mean constructing a new ontological reality. In effect, by working, the multitude produces itself as singularity. It is a singularity that establishes a new place in the non-place of Empire, a singularity that is a reality produced by cooperation, represented by the linguistic community, and developed by the movements of hybridization. The multitude affirms its singularity by inverting the ideological illusion that all humans on the global surfaces of the world market are interchangeable. Standing the ideology of the market on its feet, the multitude promotes through its labor the biopolitical singularizations of groups and sets of humanity, across each and every node of global interchange” (p. 394-395).

And from Negri & Guattari’s “New Lines of Alliance, New Lines of Hope”:

“the question lies in the proliferation of meanings with which to define the complexity of social segments, the ontological and material functions that, by converging, form a synchronic network, accumulate through history, and gradually come to form a structural totality” (p. 134).

Thinking of ways to be generative, a positivity in entanglement of “the negation of negation,” is necessary, and what Negri provides is a rather generative poetics for conceiving the extent to which any politics to come is about totalizing social relations or opening the political to the multiplicities of desire, and their realization. Notwithstanding, what is lost is how we come to understand the Empire as a spatial totality, which is in my estimation – and here I speak only to how Empire is theorized – requires an approach to thinking about something like Empire as if it has something akin to a pure form. From another angle: we now view the exercise of theorizing the atom outside an electron microscope to be rather silly, however the generation of these physical technologies had *historically required such theories. And the same will be true of the political qua multitude. What is difficult, however, is in putting Empire in its totality we must consider Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri more clearly. The point of departure of Empire’s totality is them, and as well the difficult task they ask of us: holding into a single framework, the manifold appearance of Empire. We can certainly gather around such a totality, by being its multiplicitous yet multitudinal alterity, but is it feasible?

Moreover, if we are to look at the politics which are defining our current historical conjuncture, the breaking apart of imperial desires, as they have become sedimented in supranational corporate contracts, currency markets, international financial institutions, and regional trade treaties and the physical and social infrastructures necessary for their reproduction, is every more evident. And it is coming from political forces on the right: those parties aiming to reinstantiate totalizing conceptions of the social, under the old rubric of “white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal class structure” (bell hooks, p. 18). But, as well, and most troubling: a harsher version of neoliberal socio-economic policies with the intent of re-establishing nationalist (thus, their ethnos) economy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8AtOw-xyMo8

I was perplexed that – at this moment became more evident to more people since Brexit, Trump’s election, and then Bolsonaro’s – David Harvey, in his six lectures leading up to the publication of “Marx, Capital, and the Madness of Economic Reason,” had suggested what is need at this moment is a resuscitation of “totality.” Of course, Harvey was referring to “totality” as Karl Marx had employed it, in his rigorous study emplacing Capital within its totality. As Harvey stated, in his first lecture:

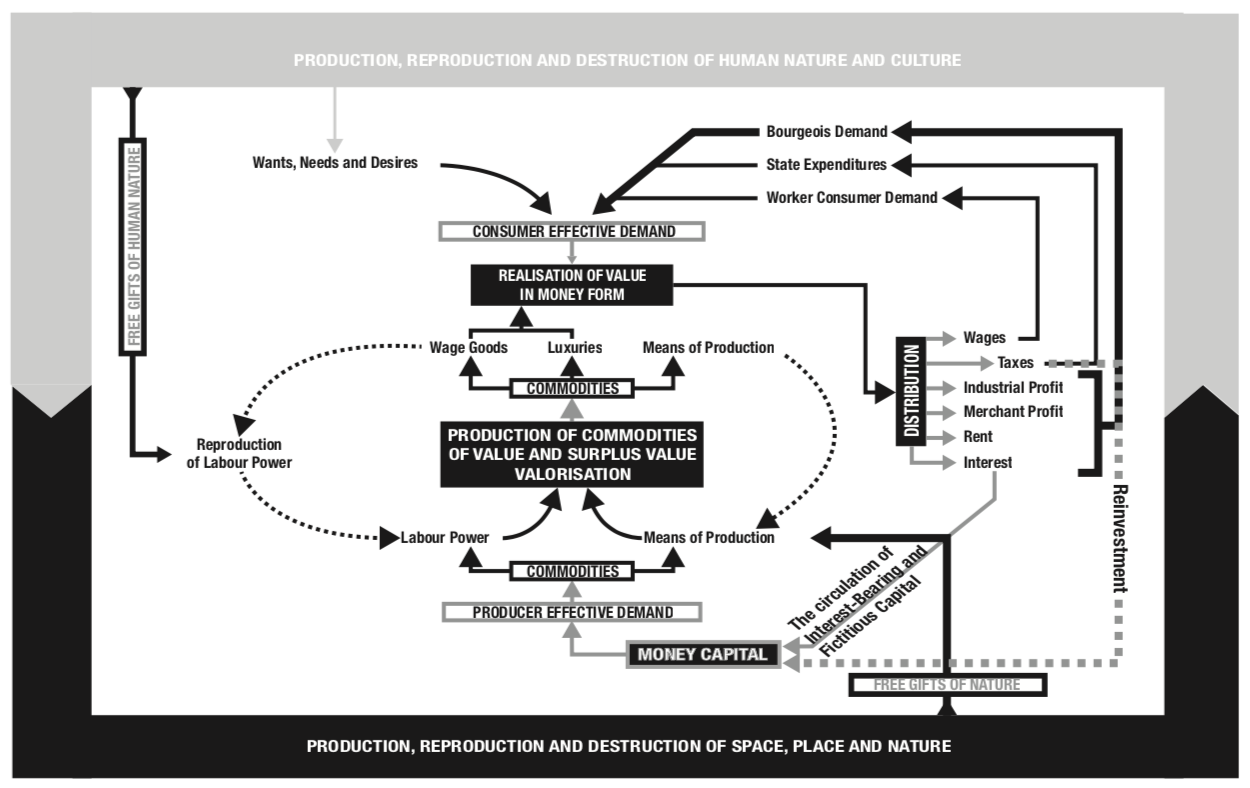

“Marx often talked about his desire to create a model of capitalist society which was modeling it as it were a totality. What that would require is putting all these models of Capital together: Volumes I, II, and III; even in their incomplete forms. Marx never tried to do that. He never got to the point that he understood … [Capital] well enough to be able to, kind of say, okay, now let’s look at the totality. I want to argue to you that in reading the volumes to Capital, you always have to this idea: the totality in mind; and ask yourself the question what is it that you’re reading in Volume III where does it lie in relationship to this totality? That is, having the visualization of what the totality of the circulation is about is extremely helpful to understand what it is you’re reading, and what you’re not reading, and why you should not draw certain inferences from what you’re reading on the basis of its positionality, in the totality… and this is what I’m trying to do [with the diagram] to provide a visualization of the totality of the circulation process. The second point is to ask: where’s the driving force in this?”

https://gcdi.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2016/09/30/david-harvey-lecture-1-capital-as-value-in-motion/

And, as Harvey writes, in his treatise on bad-infinity:

“The totality here is not that of a single organism such as the human body. It is an ecosystemic totality with multiple competing or collaborative species of activity, with an evolutionary history open to invasions, new divisions of labour and new technologies, a system in which some species and sub-systems die out while others form and flourish, at the same time as the flows of energy create dynamic changes pointing to all manner of evolutionary possibilities” (p. 46).

And, as Harvey (2010) wrote in his companion to Volume II, about how Karl Marx would have liked his works to be read:

“Marx would almost certainly want his work to be read as a totality. He would object vociferously to the idea that he could be understood adequately by way of excerpts, no matter how strategically chosen” (p. 3).

And it seems a fitting praxis for our times: returning to a rigorous analysis of the totalizing economic form through which politics from the right are re-building their power base. That is, a contradictory, yet nevertheless clear re-fastening of (semi)imperialist, white supremacist, patriarchal politics to a neoliberal form of Capital formation that builds on previous forms of (individual) Capital. Because it is difficult to hold this all within a single framework, it seems most necessary to again stoke organic intellectuals to engage in the rigorous dialectical valence and philosophical praxis which defined Karl Marx’s praxis, in order to ascertain the interconnectedness of our conjuncture to their historical antecedents and possible consequences.

And lastly, bracketing subject categories and identity formation would seem nonsensical in this enterprise, as Marx made evident in his preface to his dissertation on the seemingly esoteric exercise by the Ancient Greeks to theorize physics – out of thin air, so to say – which nevertheless defined the dominant strains of Ancient Greek philosophy, and their hegemonic concepts (i.e. the atom). In returning to now, how can the rise of finance capital be thought outside of the embodied subjectivities through which ideas about “the economy” are materialized? And, from the angle of resistance, how can we think of resistant politics and the politics of an otherwise than capital without rigorous consideration of the subjectivities through which these movements will materialize? I think we must do so by emplacing Capital in its totality, but also emplacing anti-capital in its totality.

Guattari, Félix, Stevphen Shukaitis, and Antonio Negri. 2010. New Lines of Alliance, New Spaces of Liberty. (London: Minor Compositions).

Hall, Stuart. 2000 [1984]. “Reconstruction Work: Images of Postwar Black Settlement,” in Writing Black Britain 1948-1998: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, ed. James Procter. (New York: Manchester University Press).

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

Harvey, David. 2018. A companion to Marx’s Capital. (London: Verso).

Hont, Ivan. 2005. Jealousy of trade: international competition and the nation-state in historical perspective. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

hooks, bell. 2015. Feminist theory: from margin to center. (New York: Routledge).

Marx, Karl. 1902. “The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature with an Appendix.” in Marx-Engels Collected Works, Volume 1. (Moscow: Progress Publishers).

Marx, Karl. 1969. Theories of surplus-value: part I. (Moscow: Progress Publishers).

Marx, Karl. 1990. Capital: a Critique of Political Economy, Vol. 1. trans., Ben Fowkes. (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Marx, Karl. 1992. Capital: a critique of political economy, Vol. 2. trans., David Fernbach. (London: Penguin Books).

Williams, R., 2014. Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society. (London: Oxford University Press).

I just want to respond quickly to Austin’s liberal pluralist suggestion that we may need to think of social “totality” as “totalities” in order to avoid reifiying the term, if I’m reading his post correctly. I think that the point of “totality,” as opposed to “immediacy,” from a Marxist perspective is already meant to avoid reification. I’m thinking about Lukac’s development of the term in his work on the standpoint of the proletariat, which has its problems, but can be helpful here.

Drawing on the fetishism of the commodity that Marx outlines in the first volume of Capital, Lukacs argues that reification is a product of the universalization of commodity exchange under capitalism. In other words, the world of commodity exchange renders relations between people into relations between things. It is the “thingification” of these relations, as well as that of the natural world, that acts on the consciousness of members of both the bourgeoisie and proletariat alike. Lukacs claims that reified consciousness places emphasis on immediacy in the analysis of phenomena (he addresses the realms of history and economics) and lacks the categories of mediation necessary to understand relationships between phenomena within a greater social totality and in motion across time and space. Hence, levels of mediation are necessary in order to perform an objective analysis of any social totality that moves beyond the immediate circumstances of the observer, researcher, scholar, etc. Therefore, Marxists tend to emphasize “totality” in their performance of dialectical materialism to struggle against the narrowness reification consistently reproduces in the minds of people living under capitalism.

In my opinion, a movement towards thinking of totality as “totalities” simply returns us to an emphasis on immediacy, which Marxist notions of totality attempt to illuminate and to avoid.

I want to bring up a question in response to something Prof. Harvey suggested last week, and not as a rhetorical question, but one I’m genuinely confused about. Is Trump the obvious outcome of neoliberalism, at least in relation to the US election? Or, specifically, more obvious than (Hillary) Clinton? More obvious than Obama? If Obama’s deportation scheme was in fact more robust and more effective than Trump’s may ever be, if more subtle, what is particular to Trump as opposed to the other options that makes his election seem so assured in retrospect? Is it that his rhetoric capitalized on the feeling of helplessness, precarity, alienation, etc.? It seems that Clinton’s did as well, if my memory serves at least: she mobilized what we would surely call a faux feminism, for example, capitalizing on the language of empowerment and subtly suggesting that electing a woman–any woman, that is, even one who would inevitably reinforce patriarchy in all its forms, irrespective of her own gender–would be a step in the progressive direction. This seems suspiciously similar to the idea that because Barack Obama was elected president, the US is no longer racist. (And these lines of reasoning are only marginally more spurious than one that suggests the election of a blatant racist is overwhelmingly the backlash of the election of a Black president.) But Sanders also capitalized on people’s growing sense of alienation and disempowerment, and although his solutions were obviously somewhat different, if we ignore Trump’s racism and misogyny, they seemed to share an uncanny similarity in their appeals to the problems of political cronyism, campaign finance, the scandal of corporate political influence, and generally to the plight of the working-class, among others. It wasn’t uncommon to hear of Sanders supporters who would rather have voted for Trump than Clinton (irrespective of whether or how often this actually happened). I’m of course not saying that the similarity goes much beyond their rhetoric, only that it’s rhetoric that wins elections.

I am inclined to agree that neoliberalism has been slowly losing its legitimacy and so Trump represents a construction of certain new legitimacies, e.g. in his rhetoric on immigration. But is nationalist economic protectionism a new legitimation of neoliberal policies? On the other hand, we could perhaps say that protectionism is a new legitimation for the larger project of capital accumulation by the elite, although it’s not entirely clear that even the elite support massive tariffs or that they in fact benefit from them, considering the potential for tariffs to slow both circulation and expansion, where both are circulation and expansion are mechanisms necessary for accumulation.

I would certainly agree that Trump emerged from the chaos created by neoliberalism, but I’m unclear as to why he, as opposed to other candidates and elected officials, is more obviously the outcome than all the others.

One question I was left with last Wednesday was the question of why Prof. David Harvey conceptualizes of the different ‘activity spheres’ as autonomous but interdependent, rather than as mutually constitutive. I ask this because it seems that often times one activity sphere provides the means, and not only the ends, of change in another sphere. For example, in her study of the World Bank in the 1990s in Ecuador, Kate Bedford (2009) argued that the Bank sought to embed markets in more sustainable ways through the promotion of complementary love between men and women in heterosexual partnerships. Similarly, Lamia Karim (2011) showed how microcredit lending programs in Bangladesh relied on gendered roles and expectations that made women incredibly reliable borrowers. In these cases, gendered and sexual relations provide the very means for achieving neoliberal institutional arrangements and mental conceptions (and in the process are themselves constituted and altered).

Bedford, Kate. 2009. Developing Partnerships: Gender, Sexuality, and the Reformed World Bank. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Karim, Lamia. 2011. Microfinance and Its Discontents: Women in Debt in Bangladesh. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Thank you for the summary and interesting questions. I would like to comment on the last question you posed, which touches on the relationship between the neoliberal corporate elite and the state. While I obviously do not refute the idea that the neoliberal project has captured the state apparatus, I do not believe this to be a distinctive quality of the neoliberal state. The idea that the state serves the interests of the capitalist class has been central to Marxist scholarship and is a premise that tends to be easily verified in context. As such, the state’s presumed qualities of freedom and equality do not resonate. Similarly, the neoliberal state’s connection to authoritarianism, while generally true does not strike me as an exclusively neoliberal feature either. In the context of the Dominican Republic, for instance, which is one I am more familiar with, the state has not only played a pivotal role in the advancement of capitalism and class interests but the capitalist nation-state could have never materialized without the effective territorialization that authoritarian regimes enabled. In that way, it seems fair to say that the state has more or less consistently been a limitation to anticapitalist thought and action, and that these in turn have been manifested in spite of it. The state does not necessarily represent a new obstacle. Thus, where anticapitalist action is carried out needs to be strategically considered but this is not novel. I do believe, however, that the current conjuncture has reanimated the intersection of capital-nation-state in ways that are beneficial to capital and to maintain and secure a hegemonic position amidst the neoliberal legitimization crisis. The instrumentalization and redeployment of national rhetoric has been particularly evident during the Trump administration with its fervent ultra-nationalist tone against immigrants. The spatial and conceptual manifestations of the codification of difference that the state and the nation encapsulate has always been useful to capital. The infliction and organization of difference enclosed in nation-states and the subjectivities around them (citizen-worker dyad and beyond) created crucial mechanisms of control, not exclusively by fixing the spaces where processes around labor commodification become institutionalized, but creating a system of in-betweens and border crossing for bodies to navigate, to be held captive, to be criminalized; to dispose of old subjectivities, acquire new ones and negotiate their multiplicity. As such, a potential avenue for anticapitalist action, I believe, is rooted in the disarticulation of the capital-nation-state trinity (borrowing Kojin Karatani’s language) and more emphasis and research on issues around capital and difference.