[Lead Bloggers: Kathryn, Luca, and Patrick]

This week, David Harvey discussed and elaborated on Marx’s analysis of the role of finance and interest-bearing capital in the broader capitalist mode of production.

The topic had been curiously undertheorized in the Marxist, heterodox, and even mainstream economic literature through most of the 20th century. This absence is particularly odd, given the fundamental centrality of financial instruments to infrastructure construction, long-distance trade, and urbanization.

And yet as debt has increased massively relative to GDP, across the OECD and most recently in China’s consumer-debt-and-concrete urbanization boom, such issues have spurred more attention and analysis. Across the OECD, consumer debt and sovereign/public debt have ballooned to fill the consumption gap created by stagnant real wages and eviscerated corporate taxation since the early 1970s. In the wake of the extend-and-pretend pseudo-resolution of the 2008 financial crisis, the role of finance in capitalist production, circulation, and distribution has become impossible to ignore.

Classical economists often alternated between seeing financial activity as purely epiphenomenal to productive activity, or as parasitic and prone to destabilizing rounds of speculation. Mainstream modern economics, however, has often treated finance as having a neutral effect on the economy, merely facilitating exchange and having little effect on production—an attitude embodied in the fact that most governments did not include financial activities or profits in their GDP calculations until the 1970s. Since then, there have been both glib celebrations and strident critics of the growth of finance, either as one of the “most productive” sectors in the world (according to Lloyd Blankfein), or as an increasing rentier drain on productive investment and a dangerous, casino-style speculation introducing systemic risk that threatens the very “real economy” it supposedly facilitates (see Mazzucato 2018).

Harvey’s primary argument, first laid out at length in 1982’s Limits to Capital, is that finance actually performs necessary functions in smoothing out interruptions in capital circulation, closing gaps in turnover time between industries, and acting as a central nervous system for capital as a whole, ensuring that capital can move more nimbly and quickly where the market feels it’s most needed—i.e. toward the highest profit rate on offer. By unlocking capital trapped in productive or commodity form, and tapping its expected future cash value, finance speeds up turnover of the total capital in society and thus intensifies the aggregate production of surplus value.

Just like merchants and landlords—not to mention states—money lenders existed before capitalism but are tolerated by the productive capitalist class given the specific functional roles they can perform to secure the conditions for expanded capital accumulation. These actors receive a portion of the surplus value produced in production in return for speeding up capital turnover (so industrialists don’t have to wait to find an individual buyer for every product produced before starting another round of production) or by allocating individual plots of land towards their “highest and best use” for capital (by squeezing inefficient producers off the land and redistributing it to more efficient producers whose activities meet the desires of the market).

Finance makes hoards productive, by ensuring that production can begin before a hoard is amassed (as in an industrial loan), that savings can be unlocked from their waiting place (as with interest-bearing savings accounts), that a house or car can be bought long before a worker has saved up the sticker price (realizing the commodity capital more quickly), or that liability for the inevitable risks of long-distance trade or long-turnover projects can be pooled (as with insurance). Finance keeps capital on the move through the circuit by preemptively releasing it from discrepancies in timing—at least until the loan is due.

Financiers receive their share of surplus value in the form of interest, a kind of “price” paid for the time-limited use (i.e. rental) of money. Harvey argues that such functions (again, as with the state provision of infrastructure, courts, and regulation) are not strictly speaking productive of value, just as Marx argues in Volume I of Capital that a machine cannot itself produce value: such investments rather create the facilitating conditions through which workers can produce surplus value at relatively higher rates of productivity.

The problem for capital as a whole, Harvey argues, is that all of these facilitative powers are inextricable from the same qualities that give them their inherent tendency toward speculative mania and crisis. Without allowing people to own forms of property that allow them to gamble on expected returns and thus “mortgage and foreclose upon the future,” the ability to bridge these gaps will grind to a halt, and capital will have to take much more winding and slow paths through its ever-expanding circuit.

Further, as is clear from the 2008 financial crisis, such functions may pose a whole host of larger problems for a broader economy. The increasing importance of financial activity for productive corporations like General Motors, who finance purchases of their own cars is one example, possibly diverting investment from the “real” economy into such rentier operations. Further, the use of debt as a political tool has as become especially clear: indebted workers may particularly fear to strike and miss payments, unscrupulous lenders may accumulate devalued assets through foreclosure, and states are disciplined toward particular courses of policy action (as with IMF-led structural adjustment programs or the anti-Keynesian architecture of the European Central Bank). Meanwhile, many financial institutions can lend profligately despite significant moral hazard, assured that any risk they take big enough as to be systemic will be covered by a public bailout, nationalizing private losses as public debt.

These developments raise significant questions for anticapitalist strategy, regarding the nature of this mushrooming of financial assets and the balance of class forces given assetization.

Discussion Questions

1. Have increased returns on finance drained investment away from job-creating activity in the “real” productive economy, thus contributing to unemployment and a weak bargaining position for workers? What kind of empirical evidence would we need to determine whether capitalism has been fundamentally transformed by the growth of finance, perhaps shifting the balance of power within capitalist society away from industrial capital and toward financiers? What are the strategic risks of overstating the shift from surplus value production via labor exploitation to “value-grabbing” through debt, rents, and asset seizures? What are the risks of ignoring such transformations if they are happening?

2. The 2009 decision under President Obama to bail out the banks rather than mortgage-holding homeowners stirred considerable debate over alternative ways out of the crisis. Would a more social-democratic or anti-neoliberal government have been able to move toward the democratization of finance and ownership within capitalism from that moment, or would they still be disciplined by international currency markets and “investor confidence”? What kinds of “people’s structural adjustments” are possible through the electoral route, and what are the dangers of such language being co-opted by those who seek to create a simple truce between capital and labor and have abandoned the end goal of a truly democratic control of the economy? In what sense are such interventions anticapitalist? Could any kinds of finance reforms constitute partial, “non-reformist reforms” toward socialism?

3. One of the most pernicious historical forms of right-wing criticism of capitalism has taken the form of attacks limited to the parasitic, amorphous, and world-controlling power of “banksters”—as though capitalism would be moral, stable, and bountiful for all if it weren’t for Goldman Sachs charging high rates of interest. These anticapitalist analyses, which run back at least to Martin Luther, often let industrial capitalists or “small businesses” off the hook, and see shadowy “foreign” financiers (the “globalists”) as the primary source of economic instability, nation-undermining political interference, and working-class suffering. They have most famously (but not only) taken the form of antisemitic conspiracy theories, as when the Nazis taught children that the horrors of British imperialism were the result of Jewish control of the British state. This web of spooky stories, like 9/11 conspiracy theories and the alt-libertarian “Zeitgeist” movement had a certain currency among some people coming to consciousness during the Occupy Wall Street movement, and are a lot easier to get across to most people, graduate students included, than all three volumes of Capital. How does an anticapitalist movement realistically assess the power of finance capital, resist the draw in our own analysis of fairy tales that make up the “socialism of fools” (as August Bebel defined antisemitism), and—most importantly—ensure that a more structural and less demonological analysis of capitalism can empower capitalism’s victims to understand, organize, and change their situation?

=============================================

Harvey, David. 1982. The Limits to Capital. London and New York: Verso.

Mazzucato, Mariana. 2018. The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy. New York City: PublicAffairs.

Thanks for the great summary!

I’d like to think through parts of the first discussion question: 1. Have increased returns on finance drained investment away from job-creating activity in the “real” productive economy, thus contributing to unemployment and a weak bargaining position for workers? What kind of empirical evidence would we need to determine whether capitalism has been fundamentally transformed by the growth of finance, perhaps shifting the balance of power within capitalist society away from industrial capital and toward financiers? What are the strategic risks of overstating the shift from surplus value production via labor exploitation to “value-grabbing” through debt, rents, and asset seizures? What are the risks of ignoring such transformations if they are happening?

If indeed there is a shift from industrial to financial capital happening, it would certainly have an important effect on our lives. From the conditions of labor, to how to organize meaningful social movements, the structures would be quite different. Additionally, if they are happening, they are happening in certain places and for certain people. In a way that “totality” might not capture, the global economic system is uneven and fractured. Certainly changing economic structures in one place have effects throughout the global (both within and outside of neoliberal totality). However, the transition to finance (or, to avoid teleology or a narrow idea of how history works, we could say recent surge in finance) has specificities for geographies and populations. The factory still exists, both in “post-industrial” cities and in “industrializing” areas.

For insights into how to think about this empirically, we could potentially look historically to specific times, places, laws, famines, or inventions when the balance of power shifted between industrial and financial capital. Complicating this further, Karen Ho’s Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall-Street argues that the culture of Wall Street has become the dominant economic logic due to the structure of labor at those financial institutions, dislodging the idea that financial markets behave according to natural laws. This suggests that when we look at specific historic moments, we should not consider industrial or financial capital to be an ahistorical figure, but rather sets of institutions with their own cultural momentum and with specific positions in historically specific structures.

Thanks for a terrific summary Kathryn, Luca, and Patrick.

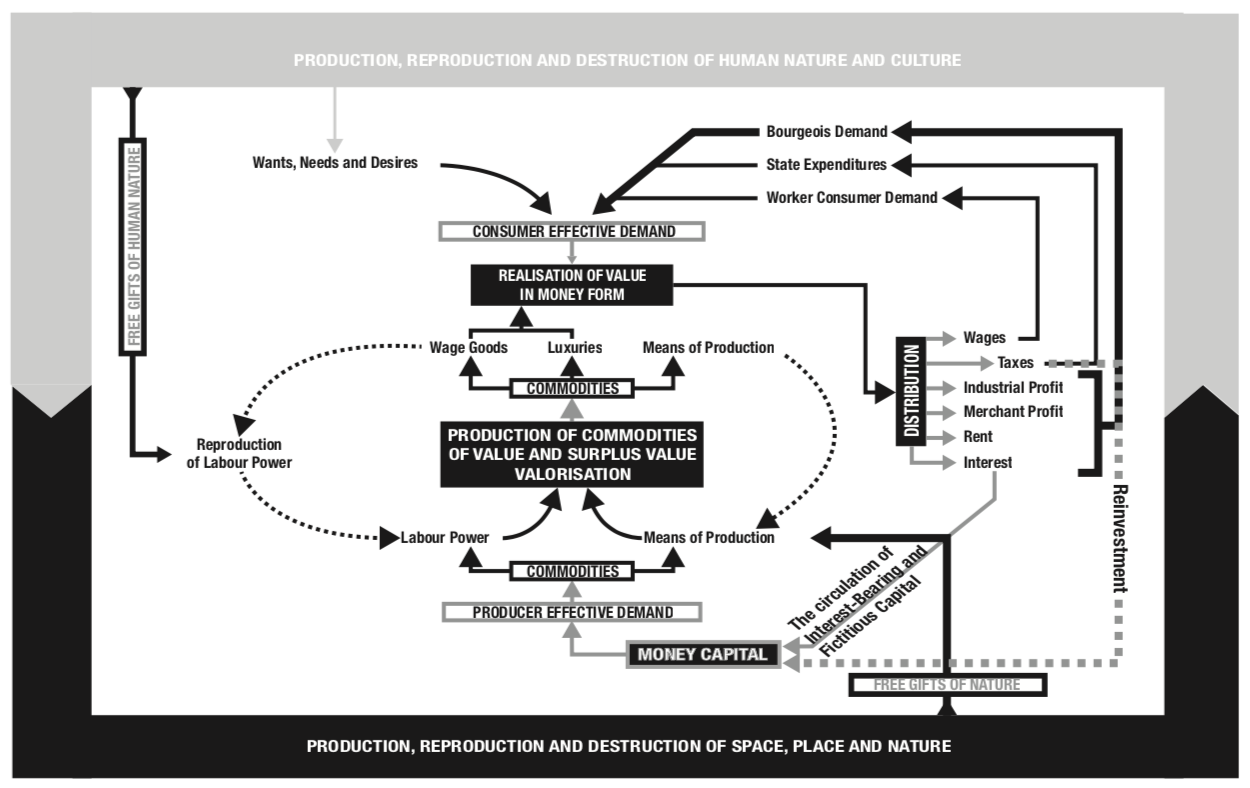

To Austin’s point about historical specificity: I don’t think that the notion of totality that Harvey offered in a past lecture or any of the analysis presented here is mutually exclusive to exploring particularities. I interpreted it as a model for understanding that if conditions of production change, so too will conditions of reproduction, the treatment of nature, etc. (or vice versa for any of the points in the diagram he drew). I didn’t see it as deterministic or as glossing specificity. As far as grand theories go I found it to be pretty amenable for the historical analysis that Austin is calling for.

The fact that the factory still exists in both industrial and post-industrial societies I think underlines this point, as the conditions under which they exist have changed which has in turn lead to different political understandings and strategies in various places. The financialization of something like say, the auto industry has drastically changed the conditions of employment and job security on the factory floor. I’m not familiar with the Ho ethnography Austin cited, but I am reminded of the analysis put forward a Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM) member in the book Detroit I Do Mind Dying, where a member says something along the lines of “if they don’t give us the factory they’ll have to move it.” And well, they did move it.

I think this might have to do with the problem that the bloggers have presented in the third question about the perennial appearance of right-wing bogeyman conspiracies. Part of the problem might be that it is easier to characterize financialization as a decrease in surplus-value production in favor of rent-seeking when in fact it has been a movement of where surplus-value production happens and an increase in the capabilities to facilitate it through finance at the same time. Antifa and anti-racist organizing does a lot of work in making this distinction, even if it’s not on these exact economic terms. The educational aspect of dismantling nationalist economic ideologies and arguing that it is not a foreigner “stealing jobs” or “taking the factory” might do a lot for lessening the appeal of right-wing bogeyman theories. Calling out those theories for what they are might be a step.

Georgakas, D., & Surkin, M. (1998). Detroit, I do mind dying (Vol. 2). South End Press.

I love that quote from DRUM! I hadn’t heard that before. Responding to question 3- I wanted to share what I think is one of the high points of class struggle, and one of the most powerful examples we have of Marxist analysis informing action– praxis– the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit. They produced a documentary about their analysis and their organizing. In the late 1960s/early 1970s, they organized wildcat strikes and organized the community against the managerial hierarchy of auto and other industries, while also confronting the racism of the UAW. This clip from their documentary is an incredibly compelling expression I know of of capital’s tendencies toward financialization that we have been discussing, as well as an analysis of how US capitalism intersects with white supremacy. Check it out!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ixo0gtLIuLk

Often it can feel like the only ideologies that gain traction in our society are the most reactionary. The experience of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers is powerful testament to the possibility of mass movements that have a lucid understanding of capitalism and how to fight it.

Also interesting is this representation around a decade later in the film “Network,” which dealt with themes of crisis, corporate capitalism, the decline of American hegemony, and conspiracy theories.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yuBe93FMiJc

Thank you for the great questions! I would like to respond to the second question –what kind of “people’s structural adjustments” of finance are possible through the electoral route– by elaborating on the idea of public banking and whether that could be made into a systematic demand to challenge the hegemony of private financial institutions.

Harvey emphasized that the 2007-8 crisis did not lead to any restructuring attempts which means that the financial system is continuing to operate on the same reckless, predatory practices and is most likely heading to another collapse within the next few years. Harvey posed the question: do we revolutionize or reform the financial system? The question of the significance of incremental change and “non-reformist reforms” have been discussed a lot in the blog. Would socialization or nationalization of banks be just one of those social-democratic reforms that will not lead to any fundamental reorganization of the system? While it will not eliminate the power of financiers right away, such reform could greatly constrain their institutions and show that a people’s alternative could replace them, while at the same time alleviating one of the most pressing problems of the ordinary people, that of indebtedness.

As the lead bloggers pointed out, Harvey argues that finance serves a necessary role in the economy as it helps to integrate different moments of production in time and space. Thus, the goal of proposed reforms should be redirecting the banking and financial system from the goal of extracting profit, which they are aggressively pursuing, to providing necessary services to the people and facilitating –instead of debilitating– the “real” economy.

This would require democratization of the governance of these institutions. While proposed reforms are usually restricted to imposing more regulations on private banks and financial institutions, the other option, which apparently does not have much popularity, or at least not prioritized, on the left, is socialization of the banking system. This means reconceiving banks as social services or public utilities providers oriented towards serving democratically determined social needs. This reconception would be based on the redefinition of values: from maximizing profit to ensuring public well-being, thus instituting use-value as the regulating principle.

Nuno Teles in his article “Socialize the Banks” suggests that we are at the conjunction when the call for public banking would be relatively easy to make (https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/04/banks-credit-recession-finance-socialism/). The 2007-8 crisis has revealed the dependence of the banks on the state and public funds, making it hard to argue that banks should be privately owned. Or, as Glen Ford says in his piece on a public banking initiative in California: after the crisis, everyone hates the banks (https://www.blackagendareport.com/california-leads-way-resistance-rule-bankers).

So what kind of restructuring can we envision? J. W. Mason suggests in his article “Socialize Finance” that we should demand that socially necessary functions like simple banking or pension funds should be brought under control of the state —thus, ultimately, of the end users— so that financial crisis would not present a collapse for daily transactions and vital savings (https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/11/finance-banks-capitalism-markets-socialism-planning). One option would be postal banking, as it is done in some countries and was done for quite a long time in the US. Yet, that wouldn’t be radical enough, as Megan Day argues in “The Case for a State-owned Bank“ relying on the recent paper by Herndon and Paul, A Public Banking Option (https://jacobinmag.com/2018/08/public-state-owned-bank-finance-nationalized-banking).

They argue that the public bank should not simply supplant alternative financial services, but compete with private banks, thus forcing them to eventually become less exploitative: “Having a fully-functioning public bank would hold traditional banks’ feet to the fire, placing ‘the burden of proof on the lender to convince the borrower that the additional loan terms added value for consumers, rather than shifting risk towards the consumer.’” (https://markpaulecon.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/public-banking-option-final.pdf).

Run not for-profit, state-owned banks would redirect local resources for local needs, offer lower interest rates (or not at all), eliminate financial costs and channel the profit back to the city or state, thus providing local government with extra revenue.

Given that most social services have been financialized, public banking would lower the costs of affordable housing and education. It would also remove the need for predatory lenders like payday loans by providing services to “underbanked” and “unbanked”.

Moreover, the availability of alternative banks accountable to the public would mean the possibility to divest from the private banks who use taxpayer money to invest in projects like Dakota Access Pipeline.

Mason also suggests that the state should buy off the debt of municipalities since many local governments — such as Puerto Rico, one of the most egregious examples– have fallen into debt peonage of the private financial institutions after having been forced or cajoled into borrowing under predatory conditions; what constituted, as Emily put it in her blog entry, “an elite coup of state operations.”

A model for this banking already exists in North Dakota. The Bank of North Dakota (BND) is owned by the state who is its only depositor (http://inthesetimes.com/article/20044/the-fight-for-public-banking). BND lends out from this deposit on far more affordable conditions to support economic development and returns its earnings back to the state. Additionally, it partners with local private banks enabling them to handle loans that they couldn’t afford otherwise, thus fostering the growth of community banks around the state.

Of course, BND also invests in projects that are against public interests, but that leads us to the question of ensuring that the people actually have access to the management of the publicly owned bank through the real control of the local government. Harvey emphasized that public ownership does not automatically mean that the banks will not continue serving private interests. Structures should be set up so that not only public officials, but other societal actors too, such as unions, consumers and elected officials –all of whom represent various interests– should participate in the governance of the banking system.

Sam Gindin, for example, brings attention to the existing practice of participatory budgeting that, if politicized and expanded, could be a means for the people to have power over budgetary decisions of redistributing local resources. Public banking could be one of the areas decided upon and regulated from below

(https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/03/workers-control-coops-wright-wolff-alperovitz/).

All of this sounds like a quite radical proposal as long as there are mechanisms to ensure democratic control. My next question is then: if we push for such reforms in banking, what other readjustments in the economic and political system must be called for to ensure that these reforms are successful?

Day, Meagan. “The Case for a State-Owned Bank.” Jacobin, August 2018.

https://jacobinmag.com/2018/08/public-state-owned-bank-finance-nationalized-banking

Dayen, David. “A Bank Even Socialist Would Love.” In These Times. April 2017.

http://inthesetimes.com/article/20044/the-fight-for-public-banking

Ford, Glen. “California Leads the Way in Resistance to the Rule of Bankers.” Black Agenda Report. July 2018.

https://www.blackagendareport.com/california-leads-way-resistance-rule-bankers

Gindin, Sam. “Chasing Utopia.” Jacobin, March 2016.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/03/workers-control-coops-wright-wolff-alperovitz/

Herndon, Thomas, and Marc Paul. A Public Banking Option: As a Mode of Regulation of Household Financial Services in the US. The Roosevelt Institute and The Samuel Dubois Cook Center on Social Equity. August 2018.

https://markpaulecon.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/public-banking-option-final.pdf

Mason, J.W. “Socialize Finance.” Jacobin, November 2016.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/11/finance-banks-capitalism-markets-socialism-planning

Teles, Nuno. “Socialize the Banks.” Jacobin, April 2016.

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/04/banks-credit-recession-finance-socialism

The capitalist system has always worked thanks to the creation of speculative bubbles. However, I ask to myself what kind of crisis create a specific kind of bubble, and if the solutions to the crisis that has been implemented emphasize the polarity in the contradiction between production and realization of value.

For example, Keynesian policies are focused on realization, and therefore have a better press among socio-democrats and a certain left, but they do not definitively resolve the contradictions of capital, they simply postpone another crisis. For example, the Great Depression after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 has not been totally overcome in the US until extensive urbanization policies were implemented. The growth of urban outskirts in American cities gave work to millions of Americans, developed the housing market and allowed millions of people to access consumption and to felt as “middle class”. The United States solved the Great Depression by means of constructing infrastructures, by a “concrete economy”. However, Keynesian policies also end up generating crises, an example of this is the stagflation suffered at the beginning of the 70s in the UK. To overcome the stagflation, neoliberal measures focused on the production of value were implemented. Neoliberalism has been an intellectual and political program that aimed that the State protects and extends markets, it has been a mechanism to make the wealthiest class even richer and more powerful by impoverishing most of society, but it has also been an answer to the stagflation produced by Keynesian policies.

In 2008 there was a financial and commercial crisis centered in the United States. A crisis that has spread to other countries and whose consequences on human lives we are still suffering. China’s reaction has been very similar to that of the United States in the 1940s and 1950s (although I do not know if it can be said that China has had Keynesian policies). China has created millions of new jobs through the creation of civil infrastructure. That is, the reaction to the crisis in both cases has been through the creation of a “fictitious” demand through the state. I say fictitious not because the infrastructures are not necessary, but because the State has had to intervene and solve the problems generated by the capitalist class in a situation where the value was focused on production and not so much on realization. The contradiction between production and realization of value has become so massive that China, by implementing a solution to the crisis, has used more concrete in 3 years than the USA used in the entire 20th century. The ecological and social consequences are obvious and undeniable. Continuing in the contradiction between production and realization of value is becoming increasingly unsustainable.

What role does finance play in all this?

For ordinary people finances has taken on an almost religious character because of their mysterious nature (it seems that finances can only be understood by those who run the financial institutions, and many times, not even by themselves), and for its sacrificial idolatry (societies make huge sacrifices to maintain financial markets that seems to be directed by ineffable forces). Finances depend to a large extent on trust and collective beliefs, they are based on a faith in the future.

Nonetheless, finances are absolutely imbricated with economic activity. As has been recall in the great summary of the class, finances “perform necessary functions in smoothing out interruptions in capital circulation” and “speed up the turnover of the total capital in society by intensifying the aggregate production of surplus value”. However, in the last decades there has been a dramatic expansion in financial flows across borders and within countries as a result of the rapid increase in telecommunications and computer-based technologies, an increase in financial markets that has been much higher than the increase in production and trade.

The rhythm of expansion has become surprising and it is clear that in recent decades there has been a distortion in the fulfillment of the functions that finance should achieve for the creation of value in production. My opinion is that the United States has forced to go globally towards this kind of economy because it foresaw that other powers would have greater productive capacity, it had to change the rules of the game to continue maintaining world’s hegemony.

The increase of global finance has had undeniable distributive effects. It has encouraged the centralization of capital in those companies with direct access to financial markets, that is, it has mainly benefited large companies. These big companies have found, through acquisitions and mergers of less powerful companies, big opportunities to appropriate the creation of productive value and increase their asset. It must to be noted that these large companies are the ones that can be introduced more easily and operate in other countries. If there is an intention in not to lose the hegemony it makes sense to promote these companies.

On the other hand, the finazialization of companies has led to a deterioration on the wage and working conditions of employees because business leaders have become solely focused on short-term enrichment of shareholders. The lowering of wages leads to a crisis in the realization of value. In a situation in which the speculative economy exceeds more than 125 times the money in circulation, it is clear that future crises will come with even worse consequences for the vast majority of the world’s population. The question is what to do with a financial system when we know that it is necessary but pernicious for the productive system. What to do with such an uncontrolled system?

In his presentation, David Harvey talked a lot about the policy initiatives developed by the Labour Party in the UK. He mentions that, under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, the Labour Party has been defending the idea of “taking public utilities back into public ownership” (https://labour.org.uk/manifesto/creating-economy-works/#eighth). Interestingly enough, those initiatives are not defined in terms of what we usually consider as “nationalization”. Indeed, as Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, John McDonnell put it “We don’t want to take power away from faceless directors to a Whitehall office, to swap one remote manager for another.” The idea is then to promote a highly democratic form of public ownership which allows workers and consumers that have a real saying in the way vital public services are managed. In that sense, it could be said that this idea is somehow based on the model of workers and peasants Soviets that emerged during the Russian Revolution and which were supposed to pave the way for a new era of democratic management of the economy in which workers and a real influence on the way their industry would be managed.

As Harvey pointed out, at a time when the vast majority of left-wing/social-democratic parties in Europe have come to embrace neoliberalism as the only game in town and have given up on their attempt to bring real change to the dominant economic model, those initiatives are particularly relevant for those of us trying to think of alternatives of the prevailing capitalist mode of production.

I also believe that it allows us to consider the role played by political parties in the fight against capitalism and “party-masses” relationships. After years of “Third Way” politics under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, the Labour Party has shifted back towards the left. This has led to a surge of membership. When Tony Blair took the leadership of the party in 1997, the Labour Party had about 400.000 members. Seven years later, in 2004, that figure had been slashed by more than half, at 190.000 members (https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2004/aug/03/uk.labour). Today, the Labout Party has 540.000 members, 4.35 times more than the Conservative Party (https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/parliament-and-elections/parliament/uk-political-party-membership-figures-august-2018/). In that sense, it could be said that the surge of membership under Corbyn’s leadership is a good illustration of the importance, for political parties of the left, to embrace a political platform that offers a real alternative to the prevailing neoliberal model, compared to most social-democratic parties which have moved to the center, giving up any attempt to change the prevailing economic structure. Those are the kind of strategies promoted by political scientist Chantal Mouffe which has theorized on the idea of a populism of the left.

– Mouffe, Chantal. 2005. On the Political. London: Routledge

– Mouffe, Chantal. 2018. For a Left Populism. New York: Verso

As Professor Harvey has pointed out, there are a variety of notions, some more coherent than others, of the concept of neoliberalism. Although Harvey’s treatment of it is significantly different from that of Foucault’s, there is at least one theme in common between Foucault’s consideration of neoliberalism in The Birth of Biopolitics and this week’s lecture by Professor Harvey: innovation and its relation to the falling rate of profit.

Foucault briefly considers the theories of Schumpeter, who sees innovation as a corrective for the falling rate of profit. Harvey’s own analysis of the falling rate of profit hinges on significant differences in the falling rate of profit chapter in volume 3 of Capital as originally published as compared to the original notebooks from which Engels developed volume 3, apparently after some fairly heavy editing. This is relevant to Foucault since he is suggesting that Schumpeter is contradicting predictions made about the falling rate of profit by classical economists and by Marx (and Foucault seems to be suggesting that those predictions are basically the same, which I don’t know enough about to comment on other than to say that the notion doesn’t seem entirely plausible). In any case, the falling rate of profit chapter in the notebooks is, according to Harvey, much less sure of itself than Engels’s edited version makes it out to be.

Either way, though, it’s notable that in Schumpeter’s analysis according to Foucault it is innovation of techniques (as well others, e.g. the innovation of finding new markets) that corrects the falling rate of profit. Maybe discovering “new techniques” here means something slightly different for Foucault than the implementation of new technologies, but it is precisely the innovative power of new technologies that Marx says causes the rate of profit to fall. For Marx, the capitalist begins using a new machine in the production process and realizes the additional surplus value he can create while his competitors use old machines, but eventually they catch up, prices fall and profits fall, and the cycle continues, etc.

This seems analogous or at least similar to a trajectory of innovation closely related to what has been called, by some theorists of neoliberalism (e.g. Wendy Brown), “the financialization of everything.” In the 1950s and 1960s, theories of finance began to change dramatically as mathematical modeling was applied to them. Considering how absolutely commonplace mathematical modeling in finance (and economics) seem today, this shift was significant, to say the least. In relation to a student’s dissertation in 1954, none other than Milton Friedman is said to have remarked that the dissertation was a mathematical exercise, not economics. That student was Harry Markowitz, who more or less invented what’s known as portfolio theory, which is essentially the mathematical proof of the folk theory that “you shouldn’t put all your eggs in one basket.” If you’ve ever heard that a stock portfolio should be diversified, you are hearing Markowitz’s theory. The practice of and the theory behind portfolio diversification literally did not exist 60 years ago. This leads to a series of other applications of mathematical models to the stock market, and eventually to credit default swaps, which are often said to be the cause of the financial crisis of 2008.

These new market theories hinge on another theoretical innovation, the “efficient market hypothesis,” which is said to name the supposed empirical reality of non-arbitrage, also known as the folk theory that prices will immediately move to their “real” value. This happens if/because all market participants have the same information about companies and their stocks, such that supply and demand will always have the effect that the accurate value of a stock will more or less immediately be reflected by its price. In other words, if a stock has a price below its value, its price will rise with near-immediacy to that value because everyone will want it—its supply will be lower than its demand, which will drive the price up until equal with its value.

Technological innovations in information processing and dissemination allow for markets to become (more) efficient, and the “discovery” of the efficient market hypothesis is then itself a kind of technological innovation that eliminates arbitrage. Like the capitalists competing in commodity production, (most) market participants are continuously pushed back toward a more or less equivalent rate of profit/return since they can’t buy stocks that have a price significantly below their value. Ditto for Markowitz’s portfolio theory, which proves that portfolio diversification as a technological innovation implies that if any market participant can eliminate certain kinds of risks through diversification, no one should be rewarded (in the form of arbitrage) for taking that risk. In other words, all these technological innovations are analogous to Marx’s improved machinery—they cause a falling rate of profit as more and more market participants adopt them. Thus each market participant is forced to move toward the general rate of profit, which itself is constantly being lowered. The problem, of course, is that each technological innovation has other implications and consequences. Technologies of industry are related to increased consumption and increased waste in the form of pollution and surplus labor. Technologies of finance, like credit default swaps, are related to increasing market volatility and risk dissemination that is not only uncontrollable but also poorly understood.

David Harvey made framed Karl Marx’s volumes on Capital in a rather strikingly way this week. Harvey said about the “power of abstraction” that Marx was only interested in the general level of abstraction, and not necessarily the particularities because they are informed by a different dynamic. From my understanding, what we have been asked to consider is why Marx intended, in short, to explain the contours of average price, and the processes informing its constitution and substance. Does, in other words, the average of prices we see in the market a byproduct of supply/demand? or, rather, does average price a wholly social form that accrues, in the context of Capital accumulation by dispossession, through competition amongst capitalists, and their trade, technological, and state wars in the quest for “growth,” markets, and monopology? Of course, I believe I am here asking rhetorical questions, and so I am speaking to the choir. Yet, I ask these questions as a pedestal from which to query anti-capital, itself.

I wonder if anti-capital praxis begins in two moments/movements: on one hand, the inclusion of social, cultural, and context particularities into the abstractions we use to frame something like a domain of the oikonomos while, in the other hand, anti-capital names a clear and sober analysis of the logics by which “total forms” are informed by (in the first instance speculation and the last totality). This sentence is purposefully agonistic, because it seems that there is nothing essential about the capitalist social position that would absolves all others from the seductions of critical criticism or the heights of abstraction; though these may be good “heights” from which to speculate (but I leave such speculation for another day). Moreover, there seems a need to consider, in our current conjuncture, possibilities *not* simply for different embodied ways of organizing politically and economically (and as well as the socially necessary relationships, like community and loved ones, such assemblages would require), but, just as significantly, “under” what concepts do we gather. Is it possible that where we might be leading ourselves astray is that we confuse “anti-capital” (a total form) with totality? In other words, to what extent has does our understanding of the power of capital (and coloniality) hampered by the broad sociological analysis necessary for understanding the breadth of the totality of something like Capital? If, say, we gesture a gentle yes to these inquiries. Then it seems incumbent that we find a new means for ascertaining and examining particularity in the face of total forms and their totality. I am not suggesting, here, that structural analysis, which we encounter for instance in the provocative work of Giorgio Agamben’s critical analysis of the political and modernity, and its convergence in modern biopolitics, is the silver bullet. Although, we should not dismiss Agamben’s writings, off hand, either. Instead, I’m wondering if we can do something as little as challenging scholarship, research, and social movements to find ways of entering particularity into the many total forms we encounter, in a manner that shifts the indices and icons of those forms? I am not so sure processual analysis are sufficient either, because there is a lack, in their methodological constitution, in looking forward. Moreover, processual analysis require that all theory be housed in the humanities. Such a separation seems to have exhausted itself, at least in our moment.

So, I want to take as my case: minimum wage. Say we consider minimum wage to be, in a certain context, a total form. This would mean we would have to consider its totality. For the sake of brevity, let’s say a brief history of minimum wage was the byproduct of spontaneous labor riots and US government triangulation. This is how I read the following passage from Howard Zinn,

“two sophisticated ways of controlling direct labor action developed in the mid-thirties. First, the National Labor Relations Board would give unions legal status, listen to them, settling certain of their grievances. Thus, it could moderate labor rebellion by channeling energy into elections-just as the constitutional system channeled possibly troublesome energy into voting. The NLRB would set limits in economic conflict as voting did in political conflict. And second, the workers’ organization itself, the union, even a militant and aggressive union like the CIO, would channel the workers’ insurrectionary energy into contracts, negotiations, union meetings, and try to minimize strikes, in order to build large, influential, even respectable organizations. The history of those years seems to support the argument of Richard Cloward and Frances Piven, in their book Poor People’s Movements, that labor won most during its spontaneous uprisings, before the unions were recognized or well organized” (1980, p. 393-394).

Zinn continues by explaining the decline in actual power once the unions became large conglomorates. What happened then was that “the members appointed to the NLRB were less sympathetic to labor, the Supreme Court declared sit-downs to be illegal, and state governments were passing laws to hamper strikes, picketing, boycotts.” (1980, p. 393)

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 was thus, for Howard Zinn, not effective in addressing the issues most pertinent to working-class people. He states, “The minimum wage of 1938, which established the forty-hour week and outlawed child labor, left many people out of its provisions and set very low minimum wages… Housing was built for only a small percentage of the people who needed it” (1980, p. 394).

The establishment of minimum wage is, in this light, a form of controlling labor but through the guise of a concession. Of course, Zinn is, here, glossing over the history; and his analysis of race and racism is inadequate. Nevertheless, it is important to note the emergence of minimum wage and its context to labor riots and government rationalization of social control.

This history is especially important when you consider other popular histories of minimum. In 2016, ABC aired its own version of the history of minimum wage. The begin by framing it “for more than a hundred years, Americans have grappled with how to fairly compensate the nation’s lowest paid workers”, and concluded by stating “as fast food workers stage marches around the country seeking the $15 dollar an hour [with emphasis] minimum wage, some economists wonder if such a drastic increase is economically sound.” The clip begins with FDR speaking over black/white images of white working-class men on farms, industry, and standing in long-lines: “if all employers will act together to shorten hours and to raise wages, we can put people back to work.” Asking businesses to provide fair wages and work-weeks did not work. And the legislation in which this language was couched, the National Industrial Recovery Act (1933), was eventually struck down by the Supreme Court in 1935. The Fair Standards Standards Act would instead include direct amendments for wages, hours, and child-labor. It was in many ways a key cog in FDR’s “New Deal.”

The ABC special is largely rehearsing the history provided on the official website of Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration and Management (OSHA). Except that OSHA emphasized that the NRA (1933) was passed in order to suspend “antitrust laws so that industries could enforce fair-trade codes resulting in less competition and higher wages”.

Then there is the Center for Poverty Research at UC-Davis, which provides the sparsest of history. They seem to think what we need to understand about minimum wage are the numbers. All statistics come from the U.S. Labor Department or U.S. Census Bureau. And as you would guess, they do not begin to challenge the very logics and socially necessary relationships informing what the economy is, in the first place.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EhreonsZU4c

https://www.dol.gov/oasam/programs/history/flsa1938.htm

https://poverty.ucdavis.edu/faq/what-history-minimum-wage

Actually, for me, one of the better analysis of what exactly minimum wage is comes of Hector Cordero-Guzman. Who recently helped publish an analysis of Puerto Rico’s minimum, which is right now under attack from the austerity board imposed by the US government to secure payments to the vulture capitalists that flooded Puerto Rico’s bond market, and exacerbated the economic problems caused by government’s reliance on corporate loopholes and government debt. Currently, Puerto Rico’s minimum wage sits at $7.25 and the austerity board would like to lower it to $4.25 for working people younger than 25 years old. In Hector’s account, he considers the work of the image of the welfare queen through which ideas about the effectiveness of minimum wage are still filtered.

https://www.primerahora.com/noticias/gobierno-politica/nota/17aspectosquedebessabersobrelajuntadecontrolfiscal-1154300/

https://www.dropbox.com/s/rj26lxcywcbwodq/Tomo%20IV-Cordero-Figueroa-Velazquez-PR-Poverty-8-16.pdf?dl=0

https://cb.pr/gobernador-firma-orden-ejecutiva-para-aumentar-salario-minimo-a-empleados-de-la-construccion-en-el-gobierno/

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/puerto-ricos-lesson-for-the-mainland/2015/07/08/24e63970-25ad-11e5-b77f-eb13a215f593_story.html

Yet, what neither of these histories or statistics account for is: what exactly does minimum wage index! The keyword here is index. By index, I mean in some ways how index is understood in Peircean semiotics, but more significantly I am referring to the previous discussions among some politicians about constructing a minimum indexed to US GDP. Mitt Romney, in particular, had the idea that to solve the issue of minimum wage by indexing it to inflation (Hillary Clinton was also on board with this “pragmatic” idea), which Romney thought was a kind of cure all since an inflation-index could also be applied to Social Security benefits.

https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2006/09/14/2006-is-year-of-surpluses-social-issues

https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/winter_2008.pdf

(p. 16)

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/21/us/politics/21debate-transcript.html

So, if both sides of the neoliberal coin, are for indexing the minimum wage, then the very idea of an indexed minimum wage should be abandoned?

I don’t think it is so easy. Rather, it seems what they had touched on briefly – now 10 years ago – was a semi-radical means for introducing dynamism into how minimum wage is assessed. However, what they were unwilling to do is use such an index to introduce particularity into the politics of minimum wage. Instead, their proposals were based on connecting minimum wage to inflation, which is confusing way to say that they wanted to minimum wage to rise (and I guess fall) according to various stages of realization. For example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics describes their process for measuring minimum wage thusly:

“Inflation has been defined as a process of continuously rising prices or, equivalently, of a continuously falling value of money. The CPI measures inflation as experienced by consumers in their day-to-day living expenses; the Producer Price Index (PPI) measures inflation at earlier stages of the production process; the International Price Program (IPP) measures inflation for imports and exports; the Employment Cost Index (ECI) measures inflation in the labor market; and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Deflator measures inflation experienced by both consumers themselves as well as governments and other institutions providing goods and services to consumers. There are also specialized measures, such as measures of interest rates.”

Which means that minimum wage would be indexed to developments in exchange-value. I will not rehearse Capital Vol. 1 here, but it is necessary to note that such an index simply links minimum wage to, in the last instance, fictious forms of capital. This, of course, hides the importance of social reproduction… etc. etc. But also, this version of an indexed wage, linking the minimum wage to inflation, would tie the minimum wage to GDP. If this ever happened, it would the biggest absurdity of all, especially given what is folded into how the GDP is currently assessed.

Michael Hudson’s (2015) assessment of “junk economics” is useful here. He explains that GDP actually includes debt payments by consumers, re-financing of mortgages, and thus the financial sector is framed as the “most productive and leading sector in the economy… instead of as an overhead the rest of the economy has to pay.”

https://youtu.be/cMuIoIidVWI?t=1003

The case of the privitization of parking in Chicago and, subsequent, erosion of affordable housing demonstrates his point:

https://youtu.be/m4ylSG54i-A?t=1295

Linking minimum wage to inflation would then to link minimum wage to GDP, and thus the not only would drive the economy but its influence on how this economy is measure in Price would be the defining index of what portion of the “growth” in fictious capital would be “compensated” to the working-poor. If I was to guess why neoliberal politicians had sought to find a pragmatic means to index the minimum while labor riots were only concerned with pushing legislation to move the absolute number of minimum wage was that they understood just how radical a indexed minimum wage could be. That is, if an indexed minimum was not linked to inflation, GDP, and fictitious capital but instead to something more practical, particular, and based on productive labor.

The minimum it seems could, instead, be indexed to a cost-of-living index (COLI). Harvard actually keeps rather keen statistics on something like a COLI with their net price calculator. It is designed so that Harvard students “can estimate how much [their] family will need to contribute for one year at Harvard.” It is a means for Harvard students to decide if attending Harvard is affordable, not simply as it pertains to tuition but in terms of wags, income, and assets; in short, the true cost of attending Harvard. On the other end, then, COLI would be those measurements which index actual expenses associated with social reproduction. It seems these calculators are now behind a paywall, but I have a link to a site allowing for public access to the calculator.

https://www.aapa.org/shop/salary-report/cost-living-calculator/

https://college.harvard.edu/financial-aid/net-price-calculator

But then these measurements will have to be radicalized, as well. The indices of these measurements are of course tied to ideas about economy linked to exchange-value and Price, and thus only indirectly to social reproduction. But how might these calculators be radicalized, if social movements put this at the forefront of their policy demands? Not only would this sort of politics force a discussion of what a “truer” idea about social reproduction looks like, but it would also radically localize these struggles without losing site of the larger nationally interconnected picture. There would be a politics around a national minimum wage nested in local indices. What would then be allowed to come to the forefront are what icons of a living-wage that are, again, geographically/historically specific. In the northern states, we would see a need to include seasonal gas prices (extended out over a year) but, in the southern states, there might be COLI that includes the need to account for electricity spikes of ACs.

As of right now, this sort of politics seems to be on the table in fights over the minimum wage. However, just because ideas of living-wage are foregrounded does not mean that there has been sufficient linking of living with the indices through which something like life or social reproduction can be measured, and moreover to what extent these are already measured for the profit of growing fictitious Capital.

And lastly, such a politics would move us away from ideas about universal basic income. I think we need to better understand the history of UBS, and it linkages to racist ideas about cognitivie distributions in society. Here is a link to a rather enlightening fight between Ezra Klein and Sam Harris. Klein does a good job of revealing the racism instilled in Charles Murray’s ideas about social policy which Murray links to biological cognitive inequalities within the population. As Klein notes, Murray goes as far as to suggest IQ testing is a legitimate means of measuring cognitivie capacity, and since people of color typically score low on these tests then of course they are biologically inferior. But, for Charles Murray, this does not mean he’s racist but a realist when it comes to social policy. A universal basic income would provide the cognitively underpriviledge with income despite their biological incapacities. Yea…..

https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2017/09/18/charles_murray_give_every_citizen_10000_a_year_in_disposable_income.html

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IeWMw2hb4gY&t=3762s

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2018/jul/29/charles-murray-conservative-economist-backs-ubi/

A minimum wage indexed to a socially responsible COLI does not get us into this mess. And it also, and this is what makes it truly radical, provides a means of cutting directly into how profit is accrued in a capital system. Rather than dramatic increased in absolute wages there would be a dynamic wage that garners a portion of the surplus-value a company can appropriate in the first place. In other words, rather than fighting every ten years or so to increase minimum wage from $10 to $15, as a way to catch up too or get in front of inflation, an indexed minimum wage rather talks about what marginal yields are socially appropriate? and, as importantly, what are the indices for a livable working conditions and social reproduction? and how do we measure them? And from this standpoint a truly radical politics can form as leisure, particularities, and margins come to the fore of politics. Of course, this idea requires further scrutiny as to its totality.

As it stands, the politics of minimum wage have not changed much and are based on legislative (state or federal) measures to expand either coverage or provision.

https://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/statutes/FairLaborStandAct.pdf

https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43089.pdf

Zinn, Howard. 1980. A people’s history of the United States: 1492-present. (New York: Longman).